Medical expert of the article

New publications

Mitral regurgitation

Last reviewed: 04.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Mitral regurgitation is a leakage of the mitral valve that results in flow from the left ventricle (LV) into the left atrium during systole. Symptoms of mitral regurgitation include palpitations, dyspnea, and a holosystolic murmur at the apex. The diagnosis of mitral regurgitation is made by physical examination and echocardiography. Patients with mild, asymptomatic mitral regurgitation should be monitored, but progressive or symptomatic mitral regurgitation is an indication for mitral valve repair or replacement.

Causes mitral regurgitation

Common causes include mitral valve prolapse, ischemic papillary muscle dysfunction, rheumatic fever, and dilation of the mitral valve annulus secondary to systolic dysfunction and left ventricular dilation.

Mitral regurgitation may be acute or chronic. Causes of acute mitral regurgitation include ischemic papillary muscle dysfunction or rupture; infective endocarditis, acute rheumatic fever; spontaneous, traumatic, or ischemic rupture or avulsion of the mitral valve leaflets or subvalvular apparatus; acute left ventricular dilation due to myocarditis or ischemia; and mechanical failure of a prosthetic mitral valve.

Common causes of chronic mitral regurgitation are similar to those of acute mitral regurgitation and also include mitral valve prolapse (MVP), dilatation of the mitral annulus, and nonischemic papillary muscle dysfunction (eg, due to left ventricular dilation). Rare causes of chronic mitral regurgitation include atrial myxoma, congenital endocardial defect with cleft anterior leaflet, SLE, acromegaly, and mitral annular calcification (mainly in older women).

In neonates, the most common causes of mitral regurgitation are papillary muscle dysfunction, endocardial fibroelastosis, acute myocarditis, cleft mitral valve with or without endocardial base defect, and myxomatous degeneration of the mitral valve. Mitral regurgitation may be associated with mitral stenosis if the thickened valve leaflets fail to close.

Acute mitral regurgitation can cause acute pulmonary edema and biventricular failure with cardiogenic shock, respiratory arrest, or sudden cardiac death. Complications of chronic mitral regurgitation include gradual enlargement of the left atrium (LA); left ventricular dilation and hypertrophy that initially compensates for the regurgitant flow (preserving stroke volume) but eventually decompensates (decreasing stroke volume); atrial fibrillation (AF) with thromboembolism; and infective endocarditis.

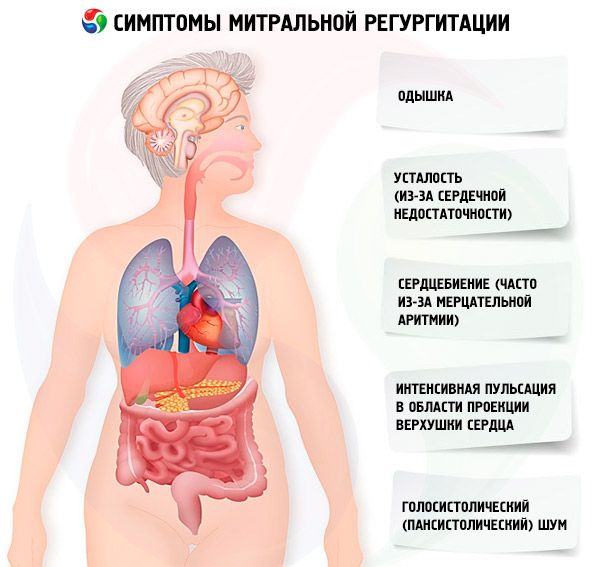

Symptoms mitral regurgitation

Acute mitral regurgitation causes symptoms similar to those of acute heart failure and cardiogenic shock. Most patients with chronic mitral regurgitation are initially asymptomatic, and clinical manifestations develop gradually as the left atrium enlarges, pulmonary pressures increase, and the left ventricle remodels. Symptoms include shortness of breath, fatigue (due to heart failure), and palpitations (often due to atrial fibrillation). Occasionally, patients develop endocarditis (fever, weight loss, embolism).

Symptoms appear when mitral regurgitation becomes moderate or severe. Inspection and palpation may reveal intense pulsation in the area of the projection of the apex of the heart and pronounced movements of the left parasternal area due to an enlarged left atrium. Left ventricular contractions that are increased, enlarged, and shifted downward and to the left indicate left ventricular hypertrophy and dilation. Diffuse precordial rise of the chest tissues occurs with severe mitral regurgitation due to an enlarged left atrium, causing anterior displacement of the heart. A regurgitant murmur (or thrill) may be felt in severe cases.

On auscultation, the first heart sound (S1) may be weakened or absent if the valve leaflets are rigid (for example, in combined mitral stenosis and mitral regurgitation due to rheumatic heart disease), but it is usually present if the leaflets are soft. The second heart sound (S2) may be split unless severe pulmonary arterial hypertension has developed. The third heart sound (S3), the loudness of which at the apex is proportional to the degree of mitral regurgitation, reflects pronounced dilation of the left ventricle. The fourth heart sound (S4) is characteristic of a recent rupture of the chordae, when the left ventricle did not have enough time to dilate.

The cardinal sign of mitral regurgitation is a holosystolic (pansystolic) murmur, heard best at the apex of the heart with the stethoscope and diaphragm, with the patient lying on the left side. In moderate mitral regurgitation, the systolic murmur is high-pitched or blowing in nature, but as flow increases it becomes low- or mid-pitched. The murmur begins at S1 under conditions that cause leaflet incompetence throughout systole (eg, destruction), but often begins after S (eg, when chamber dilation during systole distorts the valve apparatus, or when myocardial ischemia or fibrosis alters the dynamics). If the murmur begins after S2, it always continues through S3. The murmur radiates anteriorly to the left axilla; the intensity may remain the same or vary. If the intensity varies, the murmur tends to increase in volume toward S2. The mitral regurgitation murmur increases with handshaking or squatting because vascular resistance increases, increasing regurgitation into the left atrium. The murmur decreases in intensity when the patient stands or performs the Valsalva maneuver. A short, vague mid-diastolic murmur, due to abundant mitral diastolic flow, may immediately follow S2 or seem to be continuous with it.

The murmur of mitral regurgitation can be confused with tricuspid regurgitation, but with the latter the murmur increases with inspiration.

Where does it hurt?

Diagnostics mitral regurgitation

The preliminary diagnosis is made clinically and confirmed by echocardiography. Doppler echocardiography is used to detect the regurgitant flow and assess its severity. Two-dimensional echocardiography is used to identify the cause of mitral regurgitation and detect pulmonary arterial hypertension.

If endocarditis or valvular thrombi are suspected, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) can provide more detailed visualization of the mitral valve and left atrium. TEE is also indicated when mitral valve repair is planned instead of replacement, as it can confirm the absence of severe fibrosis and calcification.

Initially, an ECG and chest radiograph are usually obtained. The ECG may show left atrial enlargement and left ventricular hypertrophy with or without ischemia. Sinus rhythm is usually present if mitral regurgitation is acute because there has been no time for atrial stretching and remodeling.

Chest radiography in acute mitral regurgitation may demonstrate pulmonary edema. Changes in the cardiac shadow are not detected unless there is concomitant chronic pathology. Chest radiography in chronic mitral regurgitation may show left atrial and left ventricular enlargement. Vascular congestion and pulmonary edema are also possible in heart failure. Vascular congestion in the lungs is limited to the right upper lobe in approximately 10% of patients. This variant is probably associated with dilation of the right upper lobe and central pulmonary veins due to selective regurgitation into these veins.

Cardiac catheterization is performed before surgery, primarily to detect coronary artery disease. A prominent atrial systolic wave is detected by measuring pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (pulmonary capillary wedge pressure) during ventricular systole. Ventriculography can be used to quantify mitral regurgitation.

What do need to examine?

Who to contact?

Treatment mitral regurgitation

Acute mitral regurgitation is an indication for emergency mitral valve repair or replacement. Patients with ischemic papillary muscle rupture may also require coronary revascularization. Sodium nitroprusside or nitroglycerin can be given before surgery to reduce afterload, thereby improving stroke volume and reducing ventricular volume and regurgitation.

Radical treatment of chronic mitral regurgitation is mitral valve plastic surgery or replacement, but in patients with asymptomatic or moderate chronic mitral regurgitation and the absence of pulmonary arterial hypertension or AF, periodic monitoring may be sufficient.

The ideal timing for surgical intervention has not been defined, but performing surgery before ventricular decompensation (echocardiographic end-diastolic diameter > 7 cm, end-systolic diameter > 4.5 cm, ejection fraction < 60%) improves outcomes and reduces the likelihood of deterioration of left ventricular function. After decompensation, ventricular function depends on reducing the afterload of mitral regurgitation, and in approximately 50% of patients with decompensation, valve replacement results in a marked decrease in ejection fraction. In patients with moderate mitral regurgitation and significant coronary artery disease, perioperative mortality is 1.5% with coronary artery bypass grafting alone and 25% with simultaneous valve replacement. If technically feasible, valve repair is preferred over replacement; Perioperative mortality is 2-4% (compared to 5-10% with prosthetics), and the long-term prognosis is quite good (80-94% survival for 5-10 years compared to 40-60% with prosthetics).

Antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated before procedures that may cause bacteremia. In rheumatic mitral regurgitation, which is moderately severe, penicillin is recommended continuously until approximately age 30 to prevent recurrence of acute rheumatic fever. In most Western countries, rheumatic fever is extremely rare after age 30, limiting the duration of necessary prophylaxis. Because long-term antibiotic therapy may result in the development of resistance in organisms that can cause endocarditis, patients receiving chronic penicillin may be given other antibiotics to prevent endocarditis.

Anticoagulants are used to prevent thromboembolism in patients with heart failure or AF. Although severe mitral regurgitation tends to separate atrial thrombi and thus prevent thrombosis to some extent, most cardiologists recommend the use of anticoagulants.

Forecast

The prognosis depends on the left ventricular function, the severity and duration of mitral regurgitation, and the severity and cause of mitral regurgitation. Once mitral regurgitation becomes severe, approximately 10% of patients develop clinical manifestations of mitral regurgitation each year thereafter. Approximately 10% of patients with chronic mitral regurgitation due to mitral valve prolapse require surgical intervention.

[ 25 ]

[ 25 ]