Medical expert of the article

New publications

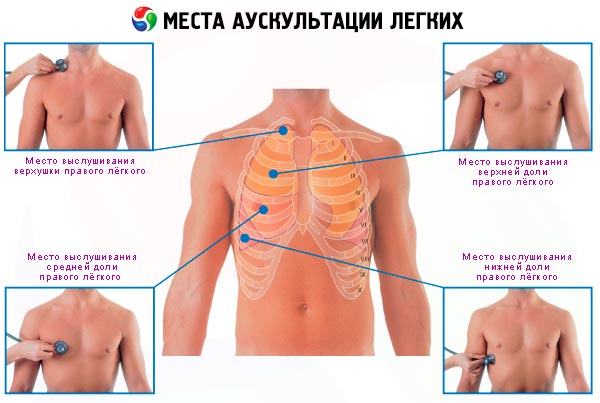

Auscultation of the lungs

Last reviewed: 04.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

The auscultatory method of examination, like percussion, also allows one to evaluate sound phenomena arising in one or another organ and indicating the physical properties of these organs. But unlike percussion, auscultation (listening) allows one to record sounds arising as a result of the natural functioning of an organ. These sounds are captured either by directly applying the ear to the area of the body of the person being examined (direct auscultation), or with the help of special capturing and conducting systems - a stethoscope and a phonendoscope (indirect auscultation).

The priority in the discovery of auscultation as one of the main methods of objective research, as already indicated, belongs to the famous French clinician R. Laennec, who, apparently, was the first to use indirect auscultation, listening to the chest of a young patient not directly with the ear, but with the help of a sheet of paper folded into a tube, which was then transformed into a special device - a cylindrical tube with two funnel-shaped expansions at the ends (stethoscope). R. Laennec thus managed to discover a number of auscultatory signs that became classic symptoms of the main diseases, primarily of the lungs, primarily pulmonary tuberculosis. At present, most doctors use indirect auscultation, although direct auscultation is also used, for example, in pediatrics.

Auscultation is especially valuable in examining the respiratory and cardiovascular systems, since the structure of these organs creates the conditions for the appearance of sound phenomena: the movement of air and blood is turbulent, but if along the course of this movement there is a narrowing (stenosis) of the bronchi and blood vessels, then the swirls of the air and blood flow become more pronounced, especially in post-stenotic areas, which intensifies the sounds that arise, the volume of which is directly proportional to the speed of the flow and the degree of narrowing of the lumen, the state of the environment (interstitial tissue, seals, cavities, the presence of liquid or gas, etc.).

In this case, the homogeneity or heterogeneity of the environment that conducts sounds is very important: the more heterogeneous the surrounding tissue, the less its resonant properties, the worse the sound phenomena reach the surface of the body.

The above-mentioned general physical regularities are especially clearly manifested in the lungs, where very specific conditions are created for the occurrence of sound phenomena when air passes through the glottis, trachea, large, medium and subsegmental bronchi, as well as when it enters the alveoli. Auscultation reveals these phenomena mainly during inhalation, but the characteristics of exhalation are also important, so the doctor necessarily evaluates inhalation and exhalation. The resulting sound phenomena are called respiratory noises. They are divided into respiratory noises, which make up the concepts of "breathing type" and "additional noises".

There are two types of breathing heard over the lungs: vesicular and bronchial.

Vesicular breathing

Vesicular breathing is normally heard over almost all areas of the chest, with the exception of the jugular fossa and interscapular region (in asthenics), where bronchial breathing is noted. It is important to remember the most important rule: if bronchial breathing is detected in any other area of the chest, then this is always a pathological sign indicating the occurrence of conditions unusual for a healthy person for better conduction of respiratory noise formed in the area of the glottis and the beginning of the trachea (most often this is a homogeneous compaction of pulmonary tissue of an inflammatory nature, for example, an infiltrate).

Although recently there has been an attempt to revise the mechanisms of formation of respiratory noises, their classical understanding proposed by Laennec retains its significance. According to traditional views, vesicular breathing (Laennec's term) occurs at the moment of appearance (entry) of air into the alveoli: contact (friction) of air with the wall of the alveoli, its rapid straightening, stretching of the elastic walls of many alveoli during inhalation create total sound vibrations that persist at the very beginning of exhalation. The second important provision is that listening to vesicular breathing or its variants (see below) over a given area always indicates that this area of the lung is “breathing”, the bronchi ventilating it are passable and air gets into this area, in contrast to the picture of a “silent” lung - a severe condition of spasm of small bronchi, blockage of their lumen with viscous secretion, for example, during the development of asthmatic status, when air does not get into the alveoli, the main respiratory noise is not heard and, as a rule, mechanical methods of restoring bronchial patency become necessary ( bronchoscopy with washing out and suction of thick secretion) until vesicular breathing is resumed.

In addition to the reduction of the bronchial lumen, hypoventilation and collapse of the lung (obstructive atelectasis due to blockage by a growing endobronchial tumor, external compression by a lymphatic or tumor node, scar tissue), weakening of vesicular breathing is caused by compression atelectasis of the lung (fluid or gas in the pleural cavity), changes in the structure of the alveolar wall - inflammation, fibrosing process, but more often loss of elastic properties in progressive pulmonary emphysema, as well as decreased mobility of the lungs (high standing of the diaphragm in obesity, Pickwickian syndrome, pulmonary emphysema, adhesions in the pleural cavity, pain due to chest trauma, rib fractures, intercostal neuralgia, dry pleurisy ).

Among the changes in vesicular breathing, there is also an increase in it (over areas close to the compaction of the lung) and the appearance of harsh breathing.

Unlike normal, with hard vesicular breathing, inhalation and exhalation are equally sonorous, while the sound phenomenon itself is rougher, contains additional noise effects associated with unevenly thickened ("rough") bronchial walls, and approaches dry wheezing. Thus, in addition to an increased (hard) inhalation, hard breathing is characterized by an increased (often extended) hard exhalation, which is usually found in bronchitis.

Bronchial breathing

In addition to vesicular, another type of respiratory noise is normally detected above the lungs - bronchial breathing, but the area of its listening is limited, as indicated, only by the area of the jugular notch, the projection site of the trachea and the interscapular region at the level of the 7th cervical vertebra. It is to these areas that the larynx and the beginning of the trachea are adjacent - the place of formation of rough vibrations of the air flow passing at high speed during inhalation and exhalation through a narrow glottis, which causes equally sonorous loud sound phenomena on inhalation and exhalation, which, however, are not conducted, normally, to most of the surface of the chest due to the heterogeneity of the environment created by the air pulmonary tissue.

R. Laennec describes bronchial breathing as follows: "... This is the sound that inhalation and exhalation make perceptible to the ear in the larynx, trachea, and large bronchial trunks located at the root of the lungs. This sound, heard when placing a stethoscope over the larynx or cervical trachea, has quite characteristic features. The respiratory noise loses its soft crackling, it is drier... and one can clearly feel that the air passes into an empty and rather wide space."

It should be emphasized once again that listening to bronchial breathing over any other area of the lung always indicates a pathological process.

Conditions for better conduction of bronchial breathing to the periphery arise first of all with compaction of lung tissue and preservation of air patency of ventilating bronchi, primarily with infiltrate (pneumonia, tuberculosis, thromboembolic pulmonary infarction ) and atelectasis (initial stages of obstructive atelectasis, compression atelectasis), but also in the presence of a cavity (cavern, emptying abscess), the air of which communicates with the air column of the bronchus, trachea, larynx, and the cavity itself is also surrounded by denser lung tissue. The same conditions for conducting bronchial breathing are created with large "dry" bronchiectasis. Sometimes over a superficially located cavity, especially if its wall is smooth and tense, bronchial breathing acquires a peculiar metallic tint - the so-called amphoric breathing, sometimes heard over the area of pneumothorax. In the case of a malignant tumor, which also represents a compaction of the lung, bronchial breathing, however, is often not heard, since the tumor usually blocks the ventilating compacted bronchi.

In addition to the two types of respiratory noises mentioned above, a number of so-called additional respiratory noises may be heard over the lungs, which are always signs of a pathological condition of the respiratory system. These include wheezing, crepitation, and pleural friction noise.

Each of these respiratory noises has a strictly defined place of origin, and therefore their diagnostic value is very significant. Thus, wheezing is formed only in the respiratory tract (bronchi of different calibers), crepitation is an exclusively alveolar phenomenon. Pleural friction noise reflects the involvement of the pleural sheets in the process. Therefore, the specified noises are heard, preferably in the corresponding phases of breathing: wheezing - mainly at the beginning of inhalation and at the end of exhalation, crepitation - only at the height of inhalation at the moment of maximum opening of the alveoli, pleural friction noise - almost equally during inhalation and exhalation throughout their entire length. The sound characteristics of the respiratory noises heard are extremely diverse, they are often compared to the sound of various musical instruments (flute, double bass, etc.), therefore the entire range of these sounds can be combined into a group that could be figuratively called a kind of "respiratory blues", since the timbre, specific overtones of secondary respiratory noises can really resemble the playing of some musical instruments. Thus, stridor, which occurs with stenosis of the larynx or trachea in the case of edema of the mucous membranes, the ingress of foreign bodies, the presence of a tumor, etc., is sometimes associated with the muffled sounds of playing the trumpet "under a mute". Dry bass wheezing, formed as a result of narrowing of the lumen of large bronchi (tumor, accumulations of viscous sputum in the form of "drops" or "strings"), are similar to the low sounds of bowed instruments, such as a cello or double bass; At the same time, the sounds of the flute can serve as an acoustic analogue of dry treble rales that occur in small-caliber bronchi and bronchioles due to spasm or obstruction.

Moist coarse-bubble rales, such as those heard in bronchiectasis, or fine-bubble rales, such as those heard in bronchitis or pulmonary edema, are comparable to the crackling of large or small gas bubbles bursting on the surface of a liquid. Short sounds of a "falling drop" when fluid accumulates in cavities with dense walls (long-standing tuberculous cavity, lung abscess) are similar to the abrupt blows of a hammer on the keys of a xylophone. Crepitation, i.e. the characteristic crackling that occurs in the alveoli partially filled with exudate in pneumonia, fibrosing alveolitis, etc., at the moment of their "explosive" straightening at the height of inspiration, is traditionally compared to the crackling of cellophane. And finally, uniform repetitive movements of a clothes brush over the surface of the skin can provide an idea of the nature and mechanism of formation of pleural friction noise in fibrinous inflammation of the pleural sheets.

[ 1 ]

[ 1 ]

Wheezing

Wheezing is a respiratory noise that mainly occurs in the trachea and bronchi, in the lumen of which there is content, but sometimes in cavities communicating with the bronchus (cavern, abscess), with rapid air movement, the speed of which, as is known, is greater during inhalation (inhalation is always active, exhalation is a passive process), especially at the beginning of it, therefore wheezing is better heard at the beginning of inhalation and at the end of exhalation.

In addition to the presence of more or less dense masses in the lumen of the bronchi, set in motion by the air flow, the occurrence of wheezing is also affected by the condition of not only the lumen, but also the wall of the bronchi (primarily the inflammatory process and spasm, which lead to a narrowing of the lumen of the respiratory tube). This explains the frequency of wheezing in bronchitis and broncho-obstructive syndrome, as well as bronchial asthma and pneumonia.

R. Laennec described the phenomenon he called wheezing and detected during auscultation of the lungs as follows: "... In the absence of a more specific term, I used this word, designating as wheezing all the noises produced during breathing by the passage of air through all the fluids that may be present in the bronchi or lung tissue. These noises also accompany coughing, when it is present, but it is always more convenient to examine them during breathing." Currently, the term "wheezing" is used only in the situations indicated above, which always reflects the presence of pathological changes.

According to the nature of the sound characteristics, wheezing is divided into dry and wet; among wet wheezing, there are small-bubble, medium-bubble and large-bubble; among small-bubble wheezing, there are voiced and unvoiced wheezing.

Dry wheezing is formed when air passes through the bronchi, in the lumen of which there is a dense content - thick viscous sputum, the bronchi are narrowed due to swollen mucous membrane or as a result of bronchospasm. Dry wheezing can be high and low, have a whistling and buzzing character and are always heard throughout the entire inhalation and exhalation. The pitch of wheezing can be used to judge the level and degree of narrowing of the bronchi (bronchial obstruction): a higher timbre of sound (bronchi sibilantes) is characteristic of obstruction of small bronchi, a lower one (ronchi soncri) is noted when the bronchi of medium and large caliber are affected, which is explained by varying degrees of obstruction of the rapidly passing air stream. Dry wheezing usually reflects a generalized process in the bronchi (bronchitis, bronchial asthma ) and is therefore heard over both lungs; if dry wheezing is detected over a localized area of the lung, then this, as a rule, is a sign of a cavity, primarily a cavern, especially if such a focus is located at the apex of the lung.

Wet rales are formed when less dense masses (liquid sputum, blood, edematous fluid) accumulate in the bronchi, when the air stream moving through them produces a sound effect, traditionally compared to the effect of bursting air bubbles passing through a tube through a vessel with water. Sound sensations depend on the caliber of the bronchi (the place of their formation). A distinction is made between fine-bubble, medium-bubble and large-bubble rales. Most often, wet rales are formed in chronic bronchitis, at the stage of resolution of an attack of bronchial asthma, while fine-bubble and medium-bubble rales are not voiced, since their sonority decreases when passing through a heterogeneous environment. Of great importance is the detection of sonorous moist rales, especially fine-bubble ones, the presence of which always indicates a peribronchial inflammatory process, and in these conditions the compacted lung tissue better conducts sounds arising in the bronchi to the periphery. This is especially important for detecting foci of infiltration in the apices of the lungs (for example, tuberculosis) and in the lower parts of the lungs (for example, foci of pneumonia against the background of blood stagnation due to heart failure). Medium-bubble and large-bubble sonorous rales are less common and usually indicate the presence of partially fluid-filled cavities (cavern, abscess ) or large bronchiectasis communicating with the respiratory tract. Their asymmetric localization in the area of the apices or lower lobes of the lungs is characteristic precisely of the indicated pathological conditions, whereas in other cases these rales indicate blood stagnation in the lungs; in pulmonary edema, moist large-bubble rales are audible at a distance.

[ 2 ]

[ 2 ]

Crepitus

Crepitation is a peculiar sound phenomenon that occurs in the alveoli most often when there is a small amount of inflammatory exudate in them. Crepitation is heard only at the height of inspiration and does not depend on the cough impulse, it resembles a crackling sound, which is usually compared to the sound of friction of hair near the auricle. First of all, crepitation is an important sign of the initial and final stages of pneumonia, when the alveoli are partially free, air can enter them and at the height of inspiration cause them to dehisce; at the height of pneumonia, when the alveoli are completely filled with fibrinous exudate (the stage of hepatization), crepitation, like vesicular breathing, is naturally not heard. Sometimes crepitation is difficult to distinguish from fine-bubble sonorous rales, which, as was said, have a completely different mechanism. When differentiating these two sound phenomena, which indicate different pathological processes in the lungs, it should be borne in mind that wheezing is heard during inhalation and exhalation, while crepitation is heard only at the height of inhalation.

With some changes in the alveoli that are not of a pneumonic nature, a deep inhalation may also cause an audible alveolar phenomenon that is completely reminiscent of crepitus; this occurs in the so-called fibrosing alveolitis; this phenomenon persists for a long time (for several weeks, months and years) and is accompanied by other signs of diffuse pulmonary fibrosis (restrictive respiratory failure).

It is necessary to warn against the use of the still widespread incorrect term “crepitating wheezing”, which confuses the phenomena “crepitation” and “wheezing”, which are completely different in origin and place of occurrence.

Pleural friction rub

Pleural friction rub is a rough vibration heard (and sometimes palpated) when the visceral and parietal pleurae, altered by the inflammatory process, rub against each other. In the vast majority of cases, it is a sign of dry pleurisy as stage 1 of exudative pleurisy, as well as a subpleurally located pneumonic focus, pulmonary infarction, lung tumor, and pleural tumor. Pleural friction rub is heard equally on inhalation and exhalation, unlike wheezing, and does not change with coughing, is better heard when pressing a stethoscope on the chest, and is preserved when the anterior abdominal wall (diaphragm) moves while holding the breath.

If the inflammatory process affects the pleura near the pericardium, a so-called pleuropericardial noise occurs. The conventionality of the term is explained by the fact that the noise is associated with friction of the altered pleural sheets caused by the pulsation of the heart, and not pericarditis.

Auscultation allows us to determine the ratio of time (duration) of inhalation and exhalation, which, as already noted, is normally always presented as follows: inhalation is heard throughout, exhalation - only at the very beginning. Any prolongation of exhalation (exhalation is equal to inhalation, exhalation is longer than inhalation) is a pathological sign and usually indicates difficulty in bronchial patency.

The auscultatory method can be used to roughly determine the time of forced exhalation. To do this, a stethoscope is applied to the trachea, the patient takes a deep breath and then a sharp, quick exhalation. Normally, the time of forced exhalation is no more than 4 seconds, it increases (sometimes significantly) in all variants of broncho-obstructive syndrome (chronic bronchitis, pulmonary emphysema, bronchial asthma). At present, the bronchophony method, popular with older doctors, is rarely used - listening to whispered speech (the patient whispers words like "cup of tea"), which is well captured by the stethoscope over the compacted area of the lung, since the vibrations of the vocal cords with such a quiet voice, normally not transmitted to the periphery, are better conducted through a pneumonic or other dense focus associated with a bronchus passable for air. Sometimes bronchophony allows us to detect small and deeply located foci of compaction, when increased vocal fremitus and bronchial breathing are not detected.

A number of methodical techniques can be recommended, which in some cases allow a more accurate assessment of the revealed auscultatory phenomena. Thus, for a more accurate determination of the area over which certain pathological sounds are heard, it is advisable to move the stethoscope with each breath from the zone of normal to the zone of altered breathing. If there are pronounced pleural pains that make deep breathing difficult, first the vocal fremitus and bronchophony should be assessed, then over the area where these phenomena are altered, with one or two deep breaths it is easier to establish one or another auscultatory sign (for example, bronchial breathing in the area of increased vocal fremitus). Using single breaths, it is possible to better hear crepitation after a short cough, bypassing a series of painful deep breaths due to the involvement of the pleura in the process.

Conducting auscultation after coughing allows us to distinguish wheezing from crepitations and pleural friction noise, as well as to exclude false weakening or even absence of respiratory sounds over the pulmonary segment due to blockage of the bronchus with secretions (after coughing, respiratory sounds are well conducted).

Thus, the diagnostic value of each of the four main methods of examining the respiratory system is difficult to overestimate, although special attention in identifying diseases of these organs is traditionally given to percussion and auscultation.

With all the diversity of data obtained using these methods, it is necessary to highlight the following key points:

- During examination, the most important thing is to detect the asymmetry of the shape of the chest and the participation of its parts in the act of breathing.

- During palpation, the asymmetry of the participation of various parts of the chest in breathing is clarified, and the features of the conduction of vocal fremitus (increase and decrease) are revealed.

- Percussion primarily allows us to detect various deviations in clear pulmonary sound, depending on the predominance of air or dense elements in a given area.

- During auscultation, the type of breathing and its changes are determined, additional respiratory noises (wheezing, crepitations, pleural friction noise) and the ratio of inhalation and exhalation are assessed.

All this, together with the results of additional examination, allows us to diagnose one or another pulmonary syndrome, and then conduct a differential diagnosis, and therefore name a specific nosological form.