Medical expert of the article

New publications

Aortic regurgitation

Last reviewed: 04.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

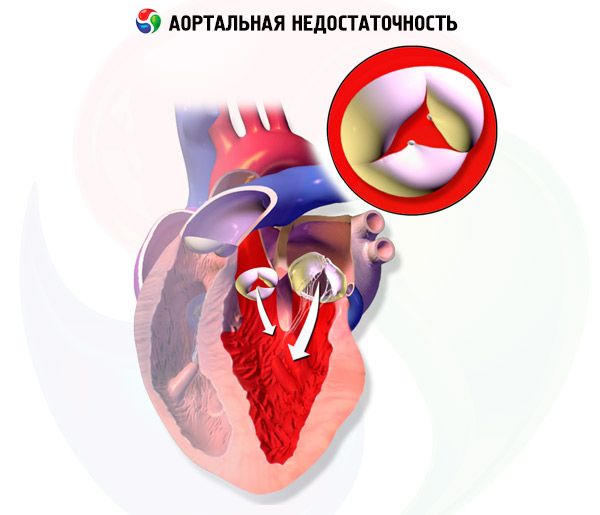

Aortic regurgitation is a failure of the aortic valve to close, resulting in flow from the aorta into the left ventricle during diastole. Causes include idiopathic valvular degeneration, acute rheumatic fever, endocarditis, myxomatous degeneration, congenital bicuspid aortic valve, syphilitic aortitis, and connective tissue or rheumatologic disease.

Symptoms include exertional dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, palpitations, and chest pain. Physical examination may reveal a diffuse pulse wave and a holodiastolic murmur. Diagnosis is made by physical examination and echocardiography. Treatment involves aortic valve replacement and (in some cases) vasodilator medications.

Causes aortic regurgitation

Aortic regurgitation (AR) can be acute or chronic. Primary causes of acute aortic regurgitation are infective endocarditis and ascending aortic dissection.

Moderate chronic aortic regurgitation in adults is most often caused by a bicuspid or fenestrated aortic valve (2% of men and 1% of women), especially if severe diastolic hypertension (BP > 110 mmHg) is present.

Moderate to severe chronic aortic regurgitation in adults is most often caused by idiopathic degeneration of the aortic valves or aortic root, rheumatic fever, infective endocarditis, myxomatous degeneration, or trauma.

In children, the most common cause is ventricular septal defect with aortic valve prolapse. Occasionally, aortic regurgitation is caused by seronegative spondyloarthropathy (ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis), RA, SLE, arthritis associated with ulcerative colitis, syphilitic aortitis, osteogenesis imperfecta, thoracic aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, supravalvular aortic stenosis, Takayasu arteritis, rupture of the sinus of Valsalva, acromegaly, and temporal (giant cell) arteritis. Aortic regurgitation due to myxomatous degeneration may develop in patients with Marfan syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

In chronic aortic regurgitation, left ventricular volume and left ventricular stroke volume gradually increase because the left ventricle receives blood from the aortic regurgitation during diastole in addition to blood from the pulmonary veins and left atrium. Left ventricular hypertrophy compensates for the increase in volume for several years, but eventually decompensation occurs. These changes may lead to arrhythmias, heart failure (HF), or cardiogenic shock.

Symptoms aortic regurgitation

Acute aortic regurgitation causes symptoms of heart failure and cardiogenic shock. Chronic aortic regurgitation is usually asymptomatic for many years; progressive dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and palpitations develop insidiously. Symptoms of heart failure correlate poorly with objective measures of left ventricular function. Chest pain (angina) occurs in approximately 5% of patients without underlying coronary artery disease, most often at night. Signs of endocarditis (eg, fever, anemia, weight loss, embolism at various sites) may develop because the abnormal aortic valve is prone to bacterial infection.

Symptoms vary with the severity of aortic regurgitation. As chronic disease progresses, systolic blood pressure increases with decreasing diastolic blood pressure, resulting in increased pulse pressure. Over time, the left ventricular impulse may intensify, widen, increase in amplitude, shift downward and to the sides, with systolic depression of the anterior left parasternal region, creating a "swinging" movement of the left half of the chest.

In later stages of aortic regurgitation, a systolic thrill may be palpated over the apex and carotid arteries; this is caused by a large stroke volume and low aortic diastolic pressure.

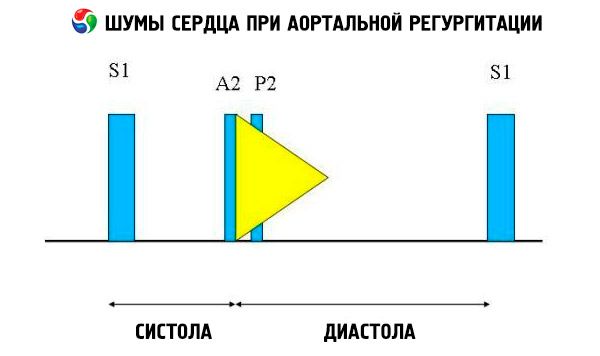

Auscultatory findings include a normal heart sound and a nonsplit, loud, pointed, or popping second heart sound due to increased resistance of the elastic aorta. The murmur of aortic regurgitation is bright, high-pitched, diastolic, fading, and begins shortly after the aortic component of S1. It is loudest in the third or fourth intercostal space to the left of the sternum. The murmur is best heard with a stethoscope with the diaphragm when the patient leans forward and holds the breath on expiration. It increases with maneuvers that increase afterload (eg, squatting, isometric handgrip). If aortic regurgitation is mild, the murmur may occur only in early diastole. If left ventricular diastolic pressure is very high, the murmur becomes shorter because aortic pressure and left ventricular diastolic pressure equalize in early diastole.

Other abnormal auscultatory findings include an ejection murmur and a regurgitant flow murmur, an ejection click shortly after S, and an aortic ejection flow murmur. A diastolic murmur heard in the axilla or mid-left hemithorax (Cole-Cecil murmur) is caused by fusion of the aortic murmur with the third heart sound (S 3 ), which occurs due to simultaneous filling of the left ventricle from the left atrium and aorta. A mid- to late diastolic murmur heard at the apex (Austin-Flint murmur) may result from rapid regurgitant flow into the left ventricle causing vibration of the mitral valve leaflet at the peak of the atrial flow; this murmur is similar to the diastolic murmur of mitral stenosis.

Other symptoms are rare and have low (or unknown) sensitivity and specificity. Visible signs include head shaking (Musset's sign) and pulsation of the nail capillaries (Quincke's sign, better felt with gentle pressure) or uvula (Müller's sign). Palpation may reveal a tense pulse with a rapid rise and fall (beating, water hammer, or collapse pulse) and pulsation of the carotid arteries (Corrigen's sign), retinal arteries (Becker's sign), liver (Rosenbach's sign), or spleen (Gerhard's sign). Blood pressure changes include increased systolic pressure in the legs (below the knee) by > 60 mmHg compared with the pressure in the arm (Hill's sign) and a drop in diastolic pressure of > 15 mmHg on raising the arm (Maine's sign). Auscultatory symptoms include a harsh murmur heard in the femoral pulse area (gunshot sound, or Traube sign), and a femoral systolic tone and diastolic murmur proximal to the compression artery (Duroziez murmur).

Diagnostics aortic regurgitation

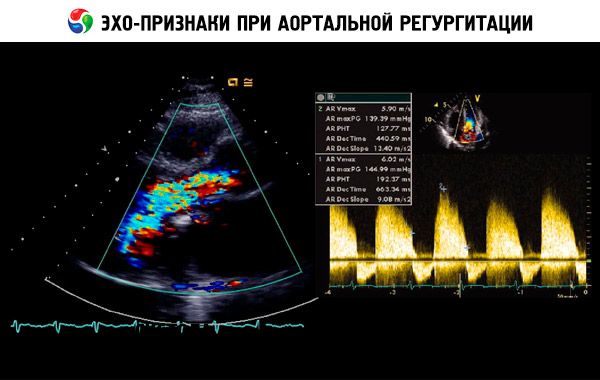

A presumptive diagnosis is made based on the history, physical examination, and confirmed by echocardiography. Doppler echocardiography is the imaging modality of choice for detecting and quantifying the magnitude of regurgitant flow. Two-dimensional echocardiography can help determine the size of the aortic root and the anatomy and function of the left ventricle. Left ventricular end-systolic volume > 60 mL/m 2, left ventricular end-systolic diameter > 50 mm, and LVEF < 50% indicate decompensation. Echocardiography can also assess the severity of pulmonary hypertension secondary to left ventricular failure, detect vegetations or pericardial effusion (eg, in aortic dissection), and assess prognosis.

Radionuclide scanning can be used to determine LVEF if echocardiographic findings are borderline abnormal or echocardiography is technically difficult to perform.

An ECG and chest radiography are performed. The ECG may demonstrate repolarization abnormalities with or without changes in the QRS complex characteristic of LV hypertrophy, left atrial enlargement, and T-wave inversion with ST-segment depression in the precordial leads. Chest radiography may reveal cardiomegaly and an enlarged aortic root in patients with chronic progressive aortic regurgitation. In severe aortic regurgitation, symptoms of pulmonary edema and heart failure may appear. Exercise testing helps to assess the functional reserve and clinical manifestations of pathology in patients with identified aortic regurgitation and questionable manifestations.

Coronary angiography is usually not needed for diagnosis, but it is performed before surgery, even in the absence of angina, since approximately 20% of patients with severe AR have severe coronary artery disease, which may be an indication for concomitant surgical treatment (CABG).

What do need to examine?

How to examine?

Who to contact?

Treatment aortic regurgitation

Treatment of acute aortic regurgitation is aortic valve replacement. Treatment of chronic aortic regurgitation depends on the clinical manifestations and the degree of LV dysfunction. Patients with symptoms that occur during normal daily activities or during exercise testing require aortic valve replacement. Patients who are unwilling to undergo surgery may be given vasodilators (eg, long-acting nifedipine 30 to 90 mg once daily or ACE inhibitors). Diuretics or nitrates may also be given to reduce preload in severe aortic regurgitation. Asymptomatic patients with LVEF < 55%, end-systolic diameter > 55 mm (rule of 55), or end-diastolic diameter > 75 mm also require surgery; drugs are the second choice for this group of patients. Additional surgical criteria include EF <25-29%, end-diastolic radius to myocardial wall thickness ratio >4.0, and cardiac index <2.2-2.5 L/min per m2.

Patients who do not meet these criteria should undergo a thorough physical examination, echocardiography, and possibly exercise and resting radionuclide angiography to determine LV contractility every 6 to 12 months.

Endocarditis prophylaxis with antibiotics is indicated before procedures that may result in bacteremia.

Forecast

With treatment, the 10-year survival rate in patients with mild to moderate aortic regurgitation is 80-95%. With timely valve replacement (before heart failure develops and taking into account the criteria described below), the long-term prognosis in patients with moderate to severe aortic regurgitation is good. However, with severe aortic regurgitation and heart failure, the prognosis is significantly worse.

[ 16 ]

[ 16 ]