Medical expert of the article

New publications

Postpartum hemorrhage

Last reviewed: 05.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Postpartum haemorrhage is generally defined as blood loss from the genital tract of more than 500 ml within 24 hours after delivery. It is the leading cause of pregnancy-related death worldwide, accounting for approximately one quarter of maternal deaths. [ 1 ] According to a systematic review, 34% of the 275 000 estimated maternal deaths globally in 2015 were due to haemorrhage. [ 2 ] This means that more than 10 deaths every hour worldwide are due to excessive obstetric haemorrhage. Most of these deaths occur in low-income countries; 2 however, women in high-income countries also continue to die from major obstetric haemorrhage. [ 3 ] In Europe, approximately 13% of obstetric patients will experience postpartum haemorrhage (≥500 ml) and about 3% will experience severe postpartum haemorrhage (≥1000 ml). [ 4 ] Moreover, PPH is associated with significant morbidity including anemia, need for blood transfusion, coagulopathy, Sheehan's syndrome (postpartum hypopituitarism), renal failure, and psychological morbidity such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. [ 5 ], [ 6 ] Active management of the third stage of labor and prophylactic administration of uterotonic drugs are the most effective strategies for preventing PPH and associated maternal mortality. [ 7 ]

Causes postpartum hemorrhage

Postpartum hemorrhage most often results from bleeding from the placental site. Risk factors for hemorrhage include uterine atony due to overdistension (caused by multiple gestations, polyhydramnios, or an excessively large fetus ), prolonged or complicated labor, multiparity (deliveries with more than five viable fetuses), use of muscle relaxants, rapid labor, chorioamnionitis, and retained placental tissue (eg, due to placenta accreta).

Other possible causes of bleeding are vaginal ruptures, rupture of an episiotomy wound, uterine rupture, and fibrous tumors of the uterus. Early postpartum hemorrhage is associated with subinvolution (incomplete involution) of the placental area, but can also occur 1 month after birth.

Postpartum hemorrhage is defined as primary if bleeding occurs before delivery of the placenta and within 24 hours of delivery of the fetus, or secondary if it occurs more than 24 hours after birth.[ 12 ] Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage include antepartum hemorrhage, augmented or induced labor, instrumental delivery or cesarean section, chorioamnionitis, fetal macrosomia, polyhydramnios, maternal anemia, thrombocytopenia or hypofibrinogenemia, maternal obesity, multiple gestation, preeclampsia, prolonged labor, placental abnormalities, and older age.[ 13 ],[ 14 ] Inherited hemostatic disorders and a history of postpartum hemorrhage in previous deliveries also increase the risk. [ 15 ], [ 16 ], [ 17 ] However, it is estimated that approximately 40% of PPH cases occur in women without any risk factors, highlighting the importance of surveillance in all women. [ 18 ]

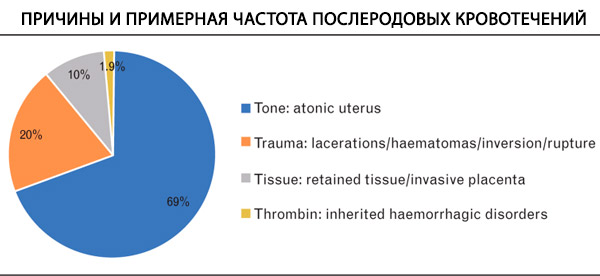

The main causes of postpartum hemorrhage can be classified into four Ts: tone, trauma, tissue, thrombin, and uterine atony, which underlies most cases. [ 19 ] Coagulopathy can worsen bleeding and contribute to the development of massive hemorrhage. They represent a state of impaired hemostasis and may include defects known before delivery or developed during or after delivery due to other complications. Causes of coagulopathy in massive hemorrhage include hyperfibrinolysis or dilutional coagulopathy due to resuscitation. Consumption coagulopathy, characterized by activation of the coagulation cascade and subsequent consumption of coagulation factors and platelets, is less common in postpartum hemorrhage but may contribute to severe cases of hemorrhage. [ 20 ] The onset and mechanism of coagulopathy depend on the etiology of the postpartum hemorrhage. In most episodes of postpartum hemorrhage (caused by uterine atony, trauma, uterine rupture), early coagulopathy is rare, whereas PPH diagnosed late or when the volume of blood loss is underestimated may be associated with an apparently earlier onset of coagulopathy. Evidence of coagulopathy is found in approximately 3% of cases of postpartum hemorrhage, with the incidence increasing with increasing hemorrhage volume.[ 21 ] Placental abruption and amniotic fluid embolism (AFE) are often associated with an early onset of coagulopathy, characterized by disseminated intravascular coagulation and hyperfibrinolysis.[ 22 ]

Pathogenesis

During pregnancy, uterine blood flow increases throughout pregnancy from approximately 100 ml/min pre-pregnancy to 700 ml/min at term, representing approximately 10% of total cardiac output, increasing the risk of massive bleeding after delivery. In addition, other significant physiological changes occur as a preventive measure to prepare the mother for blood loss and placental separation after delivery. These include profound changes in hemostasis, such as increased concentrations of certain coagulation factors, such as FVIII, von Willebrand factor (VWF), and fibrinogen, and decreased anticoagulant activity and fibrinolysis, creating a hypercoagulable state. [ 23 ], [ 24 ] During labor, blood loss is controlled by myometrial contraction, local decidual hemostatic factors, and systemic coagulation factors, and imbalances in these mechanisms may lead to postpartum hemorrhage. [ 25 ]

Diagnostics postpartum hemorrhage

The diagnosis is established on the basis of clinical data.

Who to contact?

Treatment postpartum hemorrhage

In most cases of postpartum hemorrhage, timely obstetric measures are initially stopped, including the administration of uterotonic drugs, bimanual uterine compression, removal of the retained placenta and intrauterine balloon tamponade, surgical suturing of any lacerations, in parallel with resuscitation and treatment of anemia and coagulopathy.

The intravascular volume is replenished with 0.9% sodium chloride solution up to 2 L intravenously; blood transfusion is performed if this volume of saline solution is insufficient. Hemostasis is achieved by bimanual uterine massage and intravenous administration of oxytocin; manual examination of the uterine cavity is performed to detect ruptures and remnants of placental tissue. The cervix and vagina are examined in speculums to detect ruptures; ruptures are sutured. If heavy bleeding continues with the administration of oxytocin, 15-methyl prostaglandin F2a is additionally prescribed at 250 mcg intramuscularly every 15-90 minutes up to 8 doses or methylergonovine 0.2 mg intramuscularly once (administration can be continued at 0.2 mg orally 34 times a day for 1 week). During cesarean section, these drugs can be injected directly into the myometrium. Prostaglandins are not recommended for patients with asthma; methylergonovine is undesirable for women with arterial hypertension. Sometimes misoprostol 800-1000 mcg can be used rectally to enhance uterine contractility. If hemostasis cannot be achieved, ligation of a. hypogastrica or hysterectomy is necessary.

Prevention

Risk factors such as uterine fibroids, polyhydramnios, multiple pregnancy, maternal coagulopathy, rare blood type, history of postpartum hemorrhage in previous deliveries are taken into account before delivery and, if possible, corrected. The correct approach is a gentle, unhurried delivery with a minimum of interventions. After separation of the placenta, oxytocin is administered at a dose of 10 U intramuscularly or diluted oxytocin infusions are performed (10 or 20 U in 1000 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride solution intravenously at 125-200 ml/h for 12 h), which helps improve uterine contractility and reduce blood loss. After delivery of the placenta, it is fully examined; if placental defects are detected, it is necessary to perform a manual examination of the uterine cavity with removal of residual placental tissue. Curettage of the uterine cavity is rarely required. Monitoring of uterine contractions and bleeding volume should be performed within 1 hour after completion of the 3rd stage of labor.

Sources

- 1. World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations for the Prevention and Treatment of Postpartum Haemorrhage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/75411/9789241548502_eng.pdf [Accessed 31 May 2022].

- 2. Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al.. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014; 2:e323–e333.

- 3. Kassebaum NJ, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, et al.. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016; 388:1775–1812.

- 4. Knight M, Callaghan WM, Berg C, et al.. Trends in postpartum hemorrhage in high resource countries: a review and recommendations from the International Postpartum Hemorrhage Collaborative Group. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009; 9:55.

- 5. Ford JB, Patterson JA, Seeho SKM, Roberts CL. Trends and outcomes of postpartum haemorrhage, 2003–2011. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015; 15:334.

- 6. MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers' Care. Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Inquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2017-19 2021. Available from: https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/maternal-report-2021/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_Report_2021_-_FINAL_-_WEB_VERSION.pdf. [Accessed May 31, 2022].

- 7. Calvert C, Thomas SL, Ronsmans C, et al.. Identifying regional variation in the prevalence of postpartum haemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012; 7:e41114.

- 8. Evensen A, Anderson JM, Fontaine P. Postpartum hemorrhage: prevention and treatment. Am Fam Physician 2017; 95:442–449.

- 9. Wormer KC JR, Bryant SB. Acute postpartum hemorrhage. [Updated 2020 Nov 30]. In: StatPearls, [Internet]., Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2021, Jan-., Available from:, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499988/. [Accessed May 31, 2022].

- 10. ACOG. Practice Bulletin No. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2017; 130:e168–e186.

- 11. Begley CM, Gyte GML, Devane D, et al.. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 2:CD007412-CD.

- 12. Knight M, Bunch K, Tuffnell D, Shakespeare J, Kotnis R, Kenyon S, et al. Saving lives, improving mothers' care: Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2016-18. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford 2020: p36-42.; 2019.

- 13. Rollins MD, Rosen MA. Gleason CA, Juul SE. 16 - Obstetric analgesia and anesthesia. Avery's Diseases of the Newborn (Tenth Edition). Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2018. 170–179.

- 14. Cerneca F, Ricci G, Simeone R, et al.. Coagulation and fibrinolysis changes in normal pregnancy. Increased levels of procoagulants and reduced levels of inhibitors during pregnancy induce a hypercoagulable state, combined with a reactive fibrinolysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1997; 73:31–36.

- 15. Stirling Y, Woolf L, North WR, et al.. Haemostasis in normal pregnancy. Thromb Haemost 1984; 52:176–182.

- 16. Bremme KA. Haemostatic changes in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2003; 16:153–168.

- 17. Gill P, Patel A, Van Hook J. Uterine atony. [Updated 2020 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493238/ [Accessed 12 May 2022].

- 18. Mousa HA, Blum J, Abou El Senoun G, et al. Treatment for primary postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 2014:Cd003249.

- 19. Liu CN, Yu FB, Xu YZ, et al.. Prevalence and risk factors of severe postpartum hemorrhage: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021; 21:332.

- 20. Nyfløt LT, Sandven I, Stray-Pedersen B, et al.. Risk factors for severe postpartum hemorrhage: a case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017; 17:17.

- 21. Nakagawa K, Yamada T, Cho K. Independent risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage. Crit Care Obst Gyne 2016; 2:1–7.

- 22. Wiegand SL, Beamon CJ, Chescheir NC, Stamilio D. Idiopathic polyhydramnios: severity and perinatal morbidity. Am J Perinatol 2016; 33:658–664.

- 23. Arcudi SRA, Ossola MW, Iurlaro E, et al.. Assessment of postpartum haemorrhage risk among women with thrombocytopenia: a cohort study [abstract]. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2020; 4:482–488.

- 24. Nyfløt LT, Stray-Pedersen B, Forsén L, Vangen S. Duration of labor and the risk of severe postpartum hemorrhage: a case-control study. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0175306.

- 25. Kramer MS, Dahhou M, Vallerand D, et al.. Risk Factors for Postpartum Hemorrhage: Can We Explain the Recent Temporal Increase? J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2011; 33:810–819.

- 26. Buzaglo N, Harlev A, Sergienko R, Sheiner E. Risk factors for early postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) in the first vaginal delivery, and obstetrical outcomes in subsequent pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2015; 28:932–937.

- 27. Majluf-Cruz K, Anguiano-Robledo L, Calzada-Mendoza CC, et al.. von Willebrand Disease and other hereditary haemostatic factor deficiencies in women with a history of postpartum haemorrhage. Haemophilia 2020; 26:97–105.

- 28. Main EK, Goffman D, Scavone BM, et al.. National partnership for maternal safety: consensus bundle on obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 126:155–162.

- 29. Anderson JM, Etches D. Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am Fam Physician 2007; 75:875–882.

- 30. Collis RE, Collins PW. Haemostatic management of obstetric haemorrhage. Anaesthesia 2015; 70: (Suppl 1): 78–86. e27-8.

[

[