Medical expert of the article

New publications

Hypothalamus

Last reviewed: 07.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

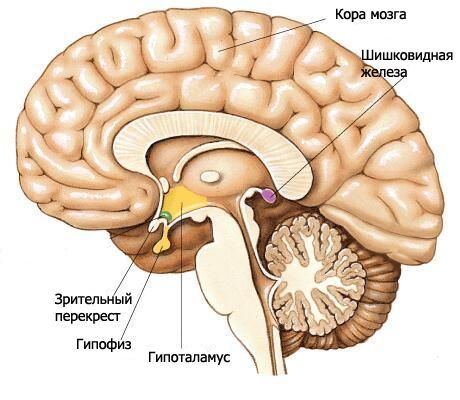

The hypothalamus forms the lower sections of the diencephalon and participates in the formation of the floor of the third ventricle. The hypothalamus includes the optic chiasm, the optic tract, the gray tubercle with the funnel, and the mammillary bodies.

The optic chiasma (chiasma opticum) is a transverse ridge formed by the fibers of the optic nerves (II pair of cranial nerves), partially crossing to the opposite side (forming a decussation). This ridge continues laterally and posteriorly on each side into the optic tract (tratus opticus). The optic tract is located medially and posteriorly from the anterior perforated substance, bends around the cerebral peduncle from the lateral side and ends with two roots in the subcortical visual centers. The larger lateral root (radix lateralis) approaches the lateral geniculate body, and the thinner medial root (radix medialis) goes to the superior colliculus of the roof of the midbrain.

The terminal plate, which belongs to the telencephalon, is adjacent to the anterior surface of the optic chiasm and fuses with it. It closes the anterior section of the longitudinal fissure of the cerebrum and consists of a thin layer of gray matter, which in the lateral sections of the plate continues into the substance of the frontal lobes of the hemispheres.

Behind the optic chiasm is the grey tubercle (tuber cinereum), behind which lie the mammillary bodies, and on the sides are the optic tracts. Below, the grey tubercle passes into the funnel (infundibulum), which connects with the pituitary gland. The walls of the grey tubercle are formed by a thin plate of grey matter containing the grey-tuberal nuclei (nuclei tuberales). From the side of the cavity of the third ventricle, a narrowing depression of the funnel projects into the region of the grey tubercle and further into the funnel.

The mammillary bodies (corpora mamillaria) are located between the gray tubercle in front and the posterior perforated substance behind. They look like two small, about 0.5 cm in diameter each, spherical white formations. The white matter is located only outside the mammillary body. Inside is the gray matter, in which the medial and lateral nuclei of the mammillary body (nuclei corporis mamillaris mediales et laterales) are distinguished. The columns of the fornix end in the mammillary bodies.

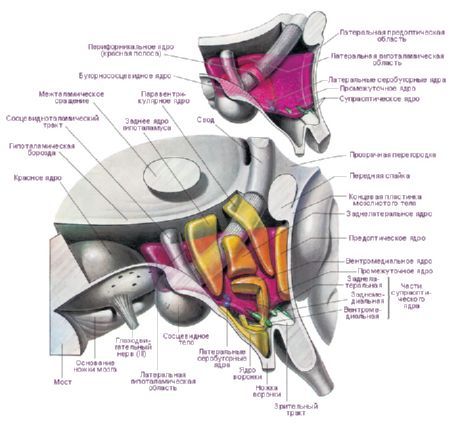

In the hypothalamus, there are three main hypothalamic regions - clusters of groups of nerve cells of different shapes and sizes: anterior (regio hypothalamica anterior), intermediate (regio hypothalamica intermedia) and posterior (regio hypothalamica posterior). Clusters of nerve cells in these regions form more than 30 nuclei of the hypothalamus.

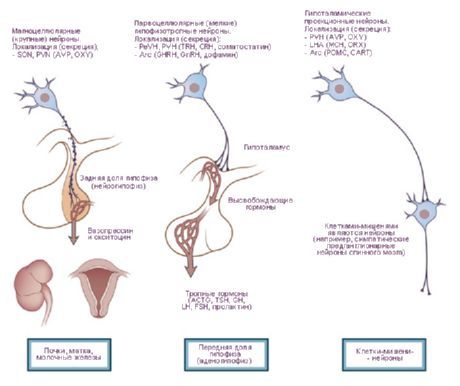

The nerve cells of the hypothalamic nuclei have the ability to produce a secretion (neurosecretion), which can be transported to the pituitary gland via the processes of these same cells. Such nuclei are called neurosecretory nuclei of the hypothalamus. In the anterior region of the hypothalamus are the supraoptic (supraoptic) nucleus (nucleus supraopticus) and the paraventricular nuclei (nuclei paraventriculares). The processes of the cells of these nuclei form the hypothalamic-pituitary bundle, ending in the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland. Among the group of nuclei of the posterior region of the hypothalamus, the largest are the medial and lateral nuclei of the mammillary body (nuclei corporis mamillaris mediales et laterales) and the posterior hypothalamic nucleus (nucleus hypothalamicus posterior). The group of nuclei of the intermediate hypothalamic region includes the inferomedial and superomedial hypothalamic nuclei (nuclei hypothalamic ventromediales et dorsomediales), the dorsal hypothalamic nucleus (nucleus hypothalamicus dorsalis), the nucleus of the infundibularis (nucleus infundibularis), the gray-tuberous nuclei (nuclei tuberales), etc.

The hypothalamus nuclei are connected by a rather complex system of afferent and efferent pathways. Therefore, the hypothalamus has a regulating effect on numerous vegetative functions of the body. The neurosecretion of the hypothalamus nuclei can influence the functions of the glandular cells of the pituitary gland, increasing or inhibiting the secretion of a number of hormones, which in turn regulate the activity of other endocrine glands.

The presence of neural and humoral connections between the hypothalamic nuclei and the pituitary gland made it possible to combine them into the hypothalamic-pituitary system.

Phylogenetic studies have shown that the hypothalamus exists in all chordates, is well developed in amphibians, and even more so in reptiles and fish. Birds have clearly expressed differentiation of nuclei. In mammals, the gray matter is highly developed, the cells of which differentiate into nuclei and fields. The human hypothalamus does not differ significantly from the hypothalamus of higher mammals.

There are a large number of classifications of the hypothalamic nuclei. E. Gruntel identified 15 pairs of nuclei, W. Le Gros Clark - 16, H. Kuhlenbek - 29. The most widely used classification is that of W. Le Gros Clark. I. N. Bogolepova (1968), based on the above classifications and taking into account ontogenesis data, proposes dividing the hypothalamic nuclei into four sections:

- anterior, or rostral, section (combining the preoptic area and the anterior group - W. Le Gros Clark) - preoptic medial and lateral areas, suprachiasmatic nucleus, supraoptic nucleus, paraventricular nucleus, anterior hypothalamic area;

- middle medial section - ventromedial nucleus, dorsomedial nucleus, infundibular nucleus, posterior hypothalamic area;

- middle lateral section - lateral hypothalamic area, lateral hypothalamic nucleus, tuberolateral nucleus, tuberomammillary nucleus, perifornical nucleus;

- posterior, or mamillary, section - medial mamillary nucleus, lateral mamillary nucleus.

The anatomical connections of the hypothalamus also clarify its (functional) significance. Among the most important afferent pathways, the following can be distinguished:

- the medial forebrain bundle, the lateral part of which connects the hypothalamus with the olfactory bulb and tubercle, the periamygdaloid region and the hippocampus, and the medial part with the septum, diagonal region, and caudate nucleus;

- the terminal strip, which runs from the tonsil to the anterior parts of the hypothalamus;

- fibers passing through the fornix from the hippocampus to the mammillary body;

- thalamo-, strio- and pallidohypothalamic connections;

- from the brainstem - the central tegmental tract;

- from the cerebral cortex (orbital, temporal, parietal).

Thus, the leading sources of afferentation are the limbic formations of the forebrain and the reticular formation of the brainstem.

The efferent systems of the hypothalamus can also be grouped into three directions:

- descending systems to the reticular formation and spinal cord - the periventricular system of fibers ending in the midbrain (longitudinal posterior bundle), at the autonomic centers of the caudal trunk and spinal cord, and the mammillary-tegmental bundle, going from the mammillary bodies to the reticular formation of the midbrain;

- pathways to the thalamus from the mammillary bodies (mammathalamic bundle), which are part of the closed functional limbic system;

- pathways to the pituitary gland - the hypothalamic-pituitary pathway from the paraventricular (10-20% of fibers) and supraoptic (80-90%) nuclei to the posterior and partially middle lobes of the pituitary gland, the tuberohypophyseal pathway from the ventromedial and infundibular nuclei to the adenohypophysis.

The works of J. Ranson (1935) and W. Hess (1930, 1954, 1968) presented data on the dilation and constriction of the pupil, the increase and decrease in arterial pressure, the acceleration and deceleration of the pulse upon stimulation of the hypothalamus. Based on these studies, zones were identified that exert sympathetic (posterior section of the hypothalamus) and parasympathetic (anterior section) effects, and the hypothalamus itself was considered as a center integrating the activity of the visceral system innervating organs and tissues. However, as these studies developed, a large number of somatic effects were also revealed, especially during free behavior of animals [Gellhorn E., 1948]. O. G. Baklavadzhan (1969), upon stimulation of various sections of the hypothalamus, observed in some cases an activation reaction in the cerebral cortex, facilitation of monosynaptic potentials of the spinal cord, an increase in arterial pressure, and in others, the opposite effect. In this case, vegetative reactions had the highest threshold. O. Sager (1962) discovered inhibition of the y-system and EEG synchronization during diathermy of the hypothalamus, and the opposite effect during excessive heating. The idea of the hypothalamus as a part of the brain that carries out interaction between regulatory mechanisms, integration of somatic and vegetative activity is formed. From this point of view, it is more correct to divide the hypothalamus not into sympathetic and parasympathetic parts, but to distinguish dynamogenic (ergotropic and trophotropic) zones in it. This classification is functional, biological in nature and reflects the participation of the hypothalamus in the implementation of holistic behavioral acts. Obviously, not only the vegetative, but also the somatic system participates in maintaining homeostasis. Ergotropic and trophotropic zones are located in all parts of the hypothalamus and overlap each other in some areas. At the same time, it is possible to identify zones of their "concentration". Thus, in the anterior sections (preoptic zone) trophotropic apparatuses are more clearly represented, and in the posterior sections (mamillary bodies) - ergotropic. Analysis of the main afferent and efferent connections of the hypothalamus with the limbic and reticular systems sheds light on its role in the organization of integrative forms of behavior. The hypothalamus occupies a special - central - position in this system both due to its topographic location in the center of these formations, and as a result of physiological features. The latter is determined by the role of the hypothalamus as a specifically constructed section of the brain, especially sensitive to shifts in the internal environment of the body, reacting to the slightest fluctuations in humoral indicators and forming expedient behavioral acts in response to these shifts. The special role of the hypothalamus is predetermined by its anatomical and functional proximity to the pituitary gland. The nuclei of the hypothalamus are divided into specific and nonspecific. The first group includes formations projecting onto the pituitary gland, the rest include other nuclei, the effects of stimulation of which may vary depending on the strength of the impact.Specific nuclei of the hypothalamus have a clear effect and differ from other brain formations in their ability to neurocrinia. These include the supraoptic, paraventricular and parvocellular nuclei of the gray tubercle. It was established that antidiuretic hormone (ADH) is formed in the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei, which descends along the axons of the hypothalamic-pituitary tract to the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland. It was later shown that releasing factors are formed in the neurons of the hypothalamus, which, entering the adenohypophysis, regulate the secretion of triple hormones: adrenocorticotropic (ACTH), luteinizing (LH), follicle-stimulating (FSH), and thyroid-stimulating (TSH). The zones of formation of the implementing factors for ACTH and TSH are the nuclei of the anterior part of the median eminence and the preoptic area, and for GTG - the posterior parts of the gray tubercle. It has been established that the hypothalamic-pituitary bundles in humans contain about 1 million nerve fibers.

Undoubtedly, other parts of the brain (medial-basal structures of the temporal region, reticular formation of the brainstem) also participate in neuroendocrine regulation. However, the most specific apparatus is the hypothalamus, which includes endocrine glands in the system of integral reactions of the body, in particular reactions of a stress nature. The tropho- and ergotropic systems have at their disposal not only the peripheral sympathetic and parasympathetic systems to ensure activity, but also specific neurohormonal apparatuses. The hypothalamic-pituitary system, functioning on the principle of feedback, is largely self-regulating. The activity of the formation of implementing factors is also determined by the level of hormones in the peripheral blood.

Thus, the hypothalamus is an important component of the limbic and reticular systems of the brain, but, being included in these systems, it retains its specific “inputs” in the form of special sensitivity to shifts in the internal environment, as well as specific “outputs” through the hypothalamic-pituitary system, paraventricular connections to the vegetative formations lying below, as well as through the thalamus and reticular formation of the brainstem to the cortex and spinal cord.

[

[