Medical expert of the article

New publications

Appendicitis

Last reviewed: 12.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Appendicitis is an acute inflammation of the appendix, usually characterized by abdominal pain, anorexia, and abdominal tenderness.

The diagnosis is established clinically, often supplemented by CT or ultrasound. [ 1 ]

Treatment of appendicitis involves surgical removal of the appendix. [ 2 ], [ 3 ]

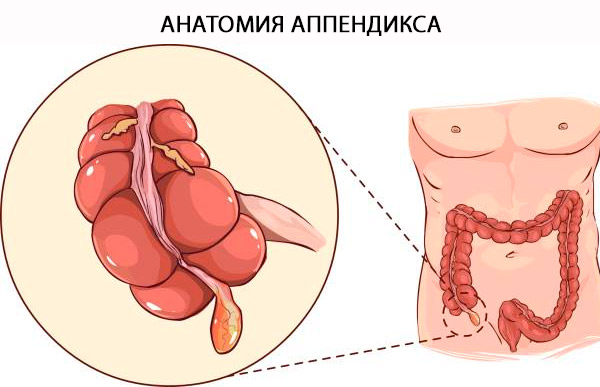

Anatomy of the appendix

The official name of the appendix is "Appendix Vermiformis". The appendix is a true diverticulum arising from the posteromedial margin of the cecum, located in close proximity to the ileocecal valve. The base of the appendix can be reliably located near the convergence of the taeniae coli at the apex of the cecum. The term "vermiformis" is Latin for "worm-shaped" [ 4 ] and is explained by its long tubular architecture. Unlike the acquired diverticulum, it is a true diverticulum of the colon, containing all layers of the colon: mucosa, submucosa, longitudinal and circular muscular coat, and serosa. The histologic distinction between the colon and the appendix depends on the presence of B and T lymphoid cells in the mucosa and submucosa of the appendix. [ 5 ]

Structure and functions

The appendix can have a variable length from 5 to 35 cm, with an average of 9 cm. [ 6 ] The function of the appendix has traditionally been a subject of debate. The neuroendocrine cells of the mucosa produce amines and hormones that help carry out various biological control mechanisms, while the lymphoid tissue is involved in the maturation of B lymphocytes and the production of IgA antibodies. There is no clear evidence for its function in humans. The presence of gut-associated lymphoid tissue in the lamina propria has led to the belief that it has an immune function, although the exact nature of this has never been established. As a result, the organ has largely retained its reputation as a vestigial organ. However, as the understanding of intestinal immunity has improved in recent years, a theory has emerged that the appendix is a "sanctuary" for symbiotic gut microbes. [ 7 ] Severe bouts of diarrhea that can clear the intestines of commensal bacteria may be replaced by drugs contained in the appendix. This suggests an evolutionary advantage in retaining the appendix and weakens the theory that the organ is vestigial. [ 8 ]

Physiological variants

Although the location of the appendiceal orifice at the base of the cecum is a stable anatomical feature, the position of its tip is not. Variations in position include retrocecal (but intraperitoneal), subcecal, pre- and postileal, pelvic, and up to the hepatorenal pouch. In addition, factors such as posture, respiration, and distention of adjacent bowel may influence the position of the appendix. The retrocecal position is the most common. This may cause clinical confusion in the diagnosis of appendicitis, since changes in position may cause different symptoms. Agenesis of the appendix, as well as duplication or triplication, are rarely described in the literature. As pregnancy progresses, the enlarging uterus displaces the appendix cranially so that by the end of the third trimester, pain with appendicitis may be felt in the right upper quadrant.

Clinical significance

The pathogenesis of acute appendicitis is similar to that of other hollow viscous organs and is thought to be most often caused by obstruction. A gallstone, or sometimes a gallstone, tumor, or worm, occludes the orifice of the appendix, causing increased intraluminal pressure and impaired venous outflow. In young adults, obstruction is more often due to lymphoid hyperplasia. The appendix receives its blood supply from the appendiceal artery, which is the terminal artery. As the intraluminal pressure exceeds the perfusion pressure, ischemic injury occurs, promoting bacterial overgrowth and causing an inflammatory response. This requires emergency surgical care, as perforation of the inflamed appendix may result in leakage of bacterial contents into the peritoneal cavity.[ 9 ]

When the wall of the appendix becomes inflamed, visceral afferent fibers are stimulated. These fibers enter the spinal cord at T8-T10, causing the classic diffuse periumbilical pain and nausea seen in early appendicitis. As the inflammation progresses, the parietal peritoneum becomes irritated, stimulating somatic nerve fibers and causing more localized pain. The location depends on the position of the apex of the appendix. For example, a retrocecal appendix may cause pain in the right flank. Extending the patient's right hip may cause this pain. Pain that occurs when the iliopsoas muscle is stretched by extending the hip in the left lateral decubitus position is known as the "psoas sign." Another classic sign of acute appendicitis is McBurney's sign. This is elicited by palpating the abdominal wall at McBurney's point (two-thirds of the distance from the umbilicus to the right anterior superior iliac spine) when pain occurs. Unfortunately, these signs and symptoms are not always present, making clinical diagnosis difficult. The clinical picture often includes nausea, vomiting, low-grade fever, and a slightly elevated white blood cell count.

Epidemiology

Acute abdominal pain accounts for 7–10% of all emergency department visits.[ 10 ] Acute appendicitis is one of the most common causes of lower abdominal pain for which patients present to the emergency department and is the most common diagnosis given to young patients admitted to the hospital with an acute abdomen.

The incidence of acute appendicitis has been steadily declining since the late 1940s. In developed countries, acute appendicitis occurs at a rate of 5.7–50 patients per 100,000 inhabitants per year, with a peak between the ages of 10 and 30 years.[ 11 ],[ 12 ]

Geographical differences have been reported, with the lifetime risk of developing acute appendicitis being 9% in the United States, 8% in Europe, and 2% in Africa.[ 13 ] Furthermore, there are large differences in the presentation, severity of disease, radiological examination, and surgical management of patients with acute appendicitis, which is related to country income.[ 14 ]

The incidence of perforations varies from 16% to 40%, with higher incidences occurring in younger age groups (40–57%) and in patients over 50 years of age (55–70%).[ 15 ]

Some authors report a gender predisposition at all ages, slightly higher among men, with a lifetime incidence of 8.6% for men and 6.7% for women.[ 16 ] However, women tend to have a higher rate of appendectomy due to various gynecological diseases that mimic appendicitis.[ 17 ]

According to population-based ethnic statistics, appendicitis is more common in white, non-Hispanic, and Hispanic groups and less common in blacks and other racial-ethnic groups.[ 18 ] However, data show that minority groups are at higher risk for perforation and complications.[ 19 ],[ 20 ]

Causes appendicitis

Appendicitis is thought to develop due to obstruction of the lumen of the appendix, usually as a result of lymphoid tissue hyperplasia, but sometimes by fecal stones, foreign bodies, or even helminths. Obstruction leads to expansion of the appendix, rapid development of infection, ischemia, and inflammation.

If left untreated, necrosis, gangrene, and perforation occur. If the perforation is covered by the omentum, an appendicular abscess forms.

In the United States, acute appendicitis is the most common cause of acute abdominal pain requiring surgical treatment.

Tumors of the appendix, such as carcinoid tumors, appendiceal adenocarcinoma, intestinal parasites, and hypertrophic lymphatic tissue, are known causes of appendiceal obstruction and appendicitis. The appendix may also be involved by Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis with pancolitis.

One of the most popular misconceptions is the story of Harry Houdini's death. After an unexpected blow to the abdomen, it is rumored that his appendix ruptured, leading to immediate sepsis and death. The facts are that Houdini did die of sepsis and peritonitis due to a ruptured appendix, but it had nothing to do with the blow to the abdomen. It had more to do with widespread peritonitis and the limited availability of effective antibiotics. [ 21 ], [ 22 ] The appendix contains aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, including Escherichia coli and Bacteroides spp. However, recent studies using next-generation sequencing have identified significantly more bacterial types in patients with complicated perforated appendicitis.

Other causes include stones, seeds, parasites such as Enterobius vermcularis (pinworms), and some rare tumors, both benign (mucinous tumors) and malignant (adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors).[ 23 ]

Risk factors

Research on the risk factors associated with acute appendicitis is limited. However, some factors that may potentially influence the likelihood of developing this disease include demographic factors such as age, gender, family history, and environmental and dietary factors. Research suggests that acute appendicitis can affect people of all ages, although it appears to be more common among adolescents and young adults, with a higher incidence seen in men.[ 24 ],[ 25 ] As with many other diseases, family history plays a significant role in acute appendicitis; evidence suggests that people with a positive family history of acute appendicitis are at increased risk of developing the disease.[ 26 ] Several dietary risk factors have been associated with appendicitis, such as a low-fiber diet, increased sugar intake, and decreased water intake. [ 27 ] Environmental factors involved in the development of appendicitis include exposure to air pollution, allergens, cigarette smoke, and gastrointestinal infections. [ 28 ], [ 29 ], [ 30 ]

New evidence suggests a potential correlation between elevated temperature and acute appendicitis, suggesting that high temperatures may increase the likelihood of developing the condition due to dehydration.[ 31 ]

Studies have also shown that patients with mental disorders who are prescribed high doses of antipsychotic drugs daily are at increased risk of developing complicated appendicitis.[ 32 ]

Symptoms appendicitis

Classic symptoms of acute appendicitis are pain in the epigastric or periumbilical region, accompanied by short-term nausea, vomiting, and anorexia; after a few hours, the pain moves to the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. The pain is aggravated by coughing and movement. [ 33 ]

Classic signs of appendicitis are localized directly in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen and at McBurney's point (a point located outward on 1/3 of the line connecting the navel and the anterior superior iliac spine), where pain is detected with a sudden decrease in pressure during palpation (e.g., Shchetkin-Blumberg symptom). [ 34 ]

Additional signs include pain that occurs in the right lower quadrant on palpation of the left lower quadrant (Rovsing's sign), increased pain with passive flexion of the right hip joint, which contracts the iliopsoas muscle (psoas sign), or pain that occurs with passive internal rotation of the flexed hip (obturator sign). A low-grade fever is common [rectal temperature 37.7-38.3° C (100-101° F)]. [ 35 ]

Unfortunately, these classic signs are observed in slightly more than 50% of patients. There are different variations of symptoms and signs.

The pain of appendicitis may not be localized, especially in infants and children. Tenderness may be diffuse or, rarely, absent. Stools are usually infrequent or absent; if diarrhea develops, retrocecal location of the appendix should be suspected. Red blood cells or white blood cells may be present in the urine. Atypical symptoms are common in older patients and pregnant women; in particular, pain and local tenderness may be mild.[ 36 ]

Anatomical aspects of acute appendicitis manifestation

The appendix is a tubular structure that attaches to the base of the cecum at the point where the taeniae coli enter. In adults, it is approximately 8–10 cm long and represents the underdeveloped distal end of the large cecum seen in other animals. In humans, it is considered a vestigial organ, and acute inflammation of this structure is called acute appendicitis.

Retrocecal/retrocolic (75%) - often presents with right lumbar pain, tenderness on examination. Muscle rigidity and tenderness on deep palpation are often absent due to protection from the overlying cecum. In this position, the psoas muscle may be irritated, causing hip flexion and increased pain on hip extension (sign of a psoas strain).

Subcecum and pelvic region (20%) - suprapubic pain and urinary frequency may predominate. Diarrhea may result from rectal irritation. Abdominal tenderness may be absent, but rectal or vaginal tenderness may be present on the right side. Microscopic hematuria and leukocytes may be present on urinalysis.

Pre- and post-ileal (5%) - signs and symptoms may be absent. Vomiting may be more severe and diarrhea may result from irritation of the distal ileum.

Symptoms of appendicitis in children

In children, appendicitis has a variability in presentation depending on age groups. [ 37 ] It is rare and difficult to diagnose in neonates and infants. [ 38 ] They typically present with abdominal distension, vomiting, diarrhea, a palpable abdominal mass, and irritability. [ 39 ] On physical examination, they often reveal dehydration, hypothermia, and respiratory distress, making a diagnosis of appendicitis unlikely for the physician. Preschool-aged children up to 3 years of age typically present with vomiting, abdominal pain, predominantly diffuse fever, diarrhea, difficulty walking, and right groin stiffness. [ 40 ] Evaluation may reveal abdominal distension, rigidity, or a mass on rectal examination. [ 41 ] Children aged 5 years and older are more likely to have classic symptoms, including migratory abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. Clinical evaluation reveals fever and tachycardia, decreased bowel sounds, and right lower quadrant tenderness, which increases the likelihood of the diagnosis in this age group.[ 42 ] The presentation of acute appendicitis in young children is usually atypical, with overlapping symptoms mimicking other systemic diseases, often leading to misdiagnosis and complications leading to morbidity. Furthermore, younger age is a well-known risk factor for adverse outcomes due to complicated appendicitis.[ 43 ]

The typical presentation of appendicitis in adults includes migratory pain in the right iliac fossa, anorexia, nausea with or without vomiting, fever, and localized rigidity/generalized rigidity.[ 44 ],[ 45 ] The classic symptom sequence includes vague umbilical pain, anorexia/nausea/transient vomiting, migratory pain in the right lower quadrant, and low-grade fever.

Atypical signs and symptoms of appendicitis

In addition to the typical presentation of appendicitis, atypical signs and symptoms may also be observed. These may include left-sided abdominal pain localized to the left upper quadrant. Although left-sided appendicitis is relatively rare, occurring in approximately 0.02% of the adult population, it is more common in people with intestinal malrotation or inverted bowel.[ 46 ] Appendicitis is also associated with diarrhea as an atypical symptom in disseminated appendicitis, especially in patients with interintestinal abscesses.[ 47 ]

In children, the symptoms are generally vague, making diagnosis difficult based on history and examination. Atypical presentation of appendicitis in children may include pain and tenderness throughout the right flank, extending from the right upper quadrant to the right iliac fossa. This may result from cecal descent arrest of the appendix, with the cecum being in a subhepatic position.[ 48 ] Adult males may present with atypical symptoms of appendicitis, such as severe right hemiplegic pain, which later becomes mild diffuse abdominal pain. In contrast, females may present with genitourinary complaints, such as thigh tenderness with a mass and diarrhea.[ 49 ],[ 50 ] In the elderly, appendicitis may present atypically as an incarcerated inguinal hernia with nonspecific symptoms.[ 51 ]

Pregnant patients are more likely to present with atypical complaints such as gastroesophageal reflux, malaise, pelvic pain, epigastric discomfort, indigestion, flatulence, dysuria, and change in bowel habits.[ 52 ] Furthermore, physical examination findings are challenging and abnormal because the abdomen is distended, increasing the distance between the inflamed appendix and the peritoneum, resulting in masking of rigidity and decreased tenderness. In late pregnancy, the appendix may displace cranially into the upper abdomen due to the enlarging uterus, resulting in RUQ pain.[ 53 ] However, regardless of gestational age, RLQ pain remains the most common clinical manifestation of acute appendicitis during pregnancy. [ 54 ] Leukocytosis may not be a reliable indicator of acute appendicitis in pregnant women due to the physiological leukocytosis during pregnancy. Studies have shown that pregnant women have a lower incidence of appendicitis than non-pregnant women. However, there is a higher risk of developing acute appendicitis in the second trimester. [ 55 ]

Complications and consequences

The predominant microbial flora associated with acute appendicitis are E. Coli, Kleibciella, Proteus, and Bacteroides (Altemeier 1938 [ 56 ]; Leigh 1974 [ 57 ]; Bennion 1990 [ 58 ]; Blewett 1995 [ 59 ]). These microbes may cause postoperative infection depending on the degree of appendiceal inflammation, surgical technique, and duration of surgery. [ 60 ]

Perforation of the appendix

Perforation of the appendix is associated with increased morbidity and mortality compared with non-perforating acute appendicitis. The mortality risk in acute but non-gangrenous acute appendicitis is less than 0.1%, but in gangrenous acute appendicitis the risk increases to 0.6%. On the other hand, perforated acute appendicitis has a higher mortality rate of about 5%. There is now increasing evidence to suggest that perforation is not necessarily an inevitable result of appendiceal obstruction, and a growing body of evidence now suggests not only that not all patients with AA will progress to perforation, but that resolution may even be common.[ 61 ]

Postoperative wound infection

The incidence of postoperative wound infection is determined by intraoperative wound contamination. The incidence of infection varies from < 5% in simple appendicitis to 20% in perforation and gangrene. The use of perioperative antibiotics has been shown to reduce the incidence of postoperative wound infections.

Intra-abdominal or pelvic abscesses

Intra-abdominal or pelvic abscesses may form in the postoperative period when the peritoneal cavity is grossly contaminated. The patient is febrile, and the diagnosis can be confirmed by ultrasound or CT scanning. Abscesses can be treated radiographically with pigtail drainage, although pelvic abscesses may require open or rectal drainage. The use of perioperative antibiotics has been shown to reduce the incidence of abscesses.

Peritonitis

If the appendix bursts, the lining of the abdomen (peritoneum) becomes infected with bacteria. This condition is called peritonitis.

Symptoms of peritonitis may include:

- severe, constant abdominal pain;

- to feel sick or to be ill;

- high temperature;

- increased heart rate;

- shortness of breath with rapid breathing;

- bloating.

If peritonitis is not treated immediately, it can cause long-term problems and even be fatal.

Diagnostics appendicitis

The Alvarado score can be used to stratify patients with symptoms suggestive of appendicitis; the reliability of the score in specific patient groups and at different points is still unclear. The Alvarado score is a useful diagnostic "rule-out" score with a cutoff of 5 for all patient groups. It is well calibrated in men, inconsistent in children, and over-predicts the likelihood of appendicitis in women across all risk strata.[ 62 ]

The Alvarado score allows risk stratification in patients with abdominal pain by relating the likelihood of appendicitis to recommendations for discharge, observation or surgery.[ 63 ] Further investigations such as ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) are recommended when the likelihood of appendicitis is in the intermediate range.[ 64 ] However, the time lag, high cost and variable availability of imaging procedures mean that the Alvarado score may be a valuable diagnostic aid when appendicitis is suspected to be the underlying cause of the acute abdomen, particularly in low-resource settings where imaging is not available.

Although the Alvarado score lacks specificity for the diagnosis of AA, a cutoff score of <5 is sensitive enough to exclude acute appendicitis (99% sensitivity). Thus, the Alvarado score may be used to reduce the length of emergency department stay and radiation exposure in patients with suspected acute appendicitis. This is supported by a large retrospective cohort study that found that 100% of men with an Alvarado score of 9 or greater and 100% of women with an Alvarado score of 10 had acute appendicitis confirmed by surgical pathology. Conversely, 5% or less of female patients with an Alvarado score of 2 or less and 0% of male patients with an Alvarado score of 1 or less were diagnosed with acute appendicitis at the time of surgery.[ 65 ]

However, the Alvarado scale does not differentiate complicated from uncomplicated acute appendicitis in elderly patients and appears to be less sensitive in HIV-positive patients.[ 66 ],[ 67 ]

The RIPASA (Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Saleh appendicitis) score showed better sensitivity and specificity than the Alvarado score in Asian and Middle Eastern populations. Malik et al. recently published the first study evaluating the utility of the RIPASA score in predicting acute appendicitis in a Western population. With a value of 7.5 (a score indicative of acute appendicitis in an Eastern population), RIPASA demonstrated reasonable sensitivity (85.39%), specificity (69.86%), positive predictive value (84.06%), negative predictive value (72.86%), and diagnostic accuracy (80%) in Irish patients with suspected AA and was more accurate than the Alvarado score.[ 68 ]

The Adult Appendicitis Score (AAS) stratifies patients into three groups: high, intermediate, and low risk for developing acute appendicitis. This score has been shown to be a reliable tool for stratifying patients for selective imaging, resulting in a low rate of negative appendectomies. In a prospective study of 829 adults with clinical suspicion of acute appendicitis, 58% of patients with histologically confirmed acute appendicitis had a score of at least 16 and were classified as a high probability group with a specificity of 93%. Patients with a score below 11 were classified as having a low probability of acute appendicitis. Only 4% of patients with acute appendicitis had a score below 11, and none of them had complications of acute appendicitis. In contrast, 54% of non-AA patients had a score below 11. The area under the ROC curve was significantly larger with the new score of 0.882 compared with the Alvarado score AUC of 0.790 and AIR of 0.810.[ 69 ]

The Alvarado score may be higher in pregnant women due to higher WBC values and incidence of nausea and vomiting, especially in the first trimester, resulting in lower accuracy compared to the non-pregnant population. Studies show that the sensitivity of the Alvarado score (cutoff 7 points) is 78.9% and specificity 80.0% in pregnant women.[ 70 ],[ 71 ] The specificity of the RIPASA score (cutoff 7.5 points) is 96%, but needs to be verified in larger studies. There are no studies on the Alvarado score that can differentiate between uncomplicated and complicated AA during pregnancy.

In the presence of classic symptoms and signs, the diagnosis is made clinically. In such patients, delaying laparotomy due to additional instrumental studies only increases the likelihood of perforation and subsequent complications. In patients with atypical or questionable data, instrumental studies should be performed without delay.

Contrast-enhanced CT has reasonable accuracy in diagnosing appendicitis and can also verify other causes of acute abdomen. Graded compression ultrasound can usually be performed more quickly than CT, but the study is sometimes limited by the presence of gas in the intestine and is less informative in the differential diagnosis of causes of nonappendiceal pain. The use of these studies has reduced the percentage of negative laparotomies.

Laparoscopy may be used for diagnosis; the study is particularly useful in women with unexplained lower abdominal pain. Laboratory studies usually show leukocytosis (12,000-15,000/μl), but these findings are highly variable; the leukocyte count should not be used as a criterion for excluding appendicitis.

The emergency department physician should refrain from prescribing any pain medications to the patient until the patient has been seen by a surgeon. Analgesics may mask peritoneal signs and lead to a delay in diagnosis or even rupture of the appendix.

Lab testing

Laboratory measurements, including total white blood cell (WBC) count, percentage of neutrophils, and C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration, are essential to continue the diagnostic workup in patients with suspected acute appendicitis.[ 72 ] Classically, an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count with or without a left shift or bandemia is present, but up to one-third of patients with acute appendicitis have normal WBC counts. Ketones are commonly detected in the urine, and C-reactive protein levels may be elevated. The combination of normal WBC and CRP results has a specificity of 98% for excluding acute appendicitis. Furthermore, WBC and CRP results have a positive predictive value for differentiating between noninflamed, uncomplicated, and complicated appendicitis. Both elevations in CRP and WBC levels correlate with a significantly increased likelihood of complicated appendicitis. The likelihood of developing appendicitis in a patient with normal WBC and CRP values is extremely low. [ 73 ] A WBC count of 10,000 cells/mm^3 is quite predictable in patients with acute appendicitis; however, the level will be increased in patients with complicated appendicitis. Accordingly, a WBC count equal to or greater than 17,000 cells/mm^3 is associated with complications of acute appendicitis, including perforated and gangrenous appendicitis.

Visualization

Appendicitis is traditionally a clinical diagnosis. However, several imaging techniques are used to guide the diagnostic steps, including abdominal CT, ultrasound, and MRI.

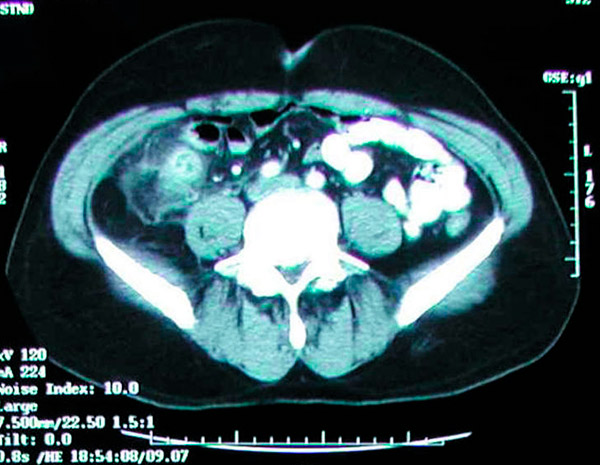

Computer tomography

Abdominal CT has an accuracy of >95% for the diagnosis of appendicitis and is increasingly used. CT criteria for appendicitis include an enlarged appendix (>6 mm in diameter), thickened appendiceal wall (>2 mm), periappendiceal fat accumulation, enhancement of the appendiceal wall, and the presence of an appendicolith (in about 25% of patients). It is unusual to see air or contrast in the lumen in appendicitis because of lumen dilation and possible obstruction in most cases of appendicitis. Failure to visualize the appendix does not exclude appendicitis. Ultrasound is less sensitive and specific than CT but may be useful to avoid ionizing radiation in children and pregnant women. MRI may also be useful in pregnant women with suspected appendicitis and an indeterminate ultrasound result. Classically, the best way to diagnose acute appendicitis is with a good history and a thorough physical examination by an experienced surgeon; however, it is very easy to obtain a CT scan in the emergency department. It has become common practice to rely primarily on CT scans to make the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Occasionally, appendicoliths are discovered incidentally on routine x-rays or CT scans.

CT scan shows an inflammatory mass in the right iliac fossa caused by acute appendicitis.

The primary concern with abdominal and pelvic CT is radiation exposure; however, the average radiation exposure from a typical CT scan will not exceed 4 mSv, which is slightly higher than the background radiation of nearly 3 mSv. Despite the higher resolution of CT images obtained with a maximum radiation dose of 4 mSv, lower doses will not affect clinical outcomes. Additionally, abdominal and pelvic CT with intravenous contrast in patients with suspected acute appendicitis should be limited to an acceptable glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 30 mL/min or greater. These patients are at higher risk of developing appendicitis than the general population. Prophylactic appendectomy should be considered in these patients. Studies have also shown that the incidence of appendicoliths in appendectomy specimens performed for acute appendicitis ranges from 10% to 30%. [ 74 ], [ 75 ], [ 76 ]

Ultrasound echography

Abdominal ultrasound is a widely used and affordable initial evaluation of patients with acute abdominal pain. A specific compressibility index of less than 5 mm in diameter is used to exclude appendicitis. In contrast, certain findings, including an anteroposterior diameter greater than 6 mm, appendicoliths, and abnormally increased echogenicity of the periappendiceal tissue, suggest acute appendicitis. The major concerns with using abdominal ultrasound to evaluate a potential diagnosis of acute appendicitis include the inherent limitations of sonography in obese patients and operator dependence in detecting suggestive features. Furthermore, graded compression is difficult to tolerate in patients complicated by peritonitis.[ 77 ]

MRI

Despite the high sensitivity and specificity of MRI in the context of detecting acute appendicitis, there are significant problems with performing abdominal MRI. Not only is performing abdominal MRI expensive, but it also requires a high level of expertise to interpret the results. Therefore, its indications are largely limited to special patient groups, including pregnant women, who have an unacceptable risk of radiation exposure. [ 78 ]

What do need to examine?

How to examine?

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes Crohn's ileitis, mesenteric adenitis, cecal diverticulum inflammation, Mittelschmerz, salpingitis, ovarian cyst rupture, ectopic pregnancy, tubo-ovarian abscess, musculoskeletal disorders, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, gastroenteritis, right-sided colitis, renal colic, kidney stones, irritable bowel disease, testicular torsion, ovarian torsion, round ligament syndrome, epididymitis, and other nondescript gastrointestinal problems. A detailed medical history and problem-oriented physical examination are necessary to exclude differential diagnoses. Accordingly, recent viral infection generally suggests acute mesenteric adenitis and worsening severe tenderness with cervical motion during transvaginal examination, which is commonly seen in pelvic inflammatory disease. One of the difficult differential diagnoses is acute Crohn's disease. Although a positive history of Crohn's disease in the past may prevent unnecessary surgical procedures, Crohn's disease may present acutely for the first time, mimicking acute appendicitis. The presence of an inflamed ileum at the time of surgery should raise the suspicion of Crohn's disease along with other bacterial causes of acute ileitis, including Yersinia or Campylobacter ileitis. The preferred approach is appendectomy, even in the absence of signs of acute appendicitis. However, in patients with signs of ileitis along with cecal inflammation, appendectomy is contraindicated, as it will further complicate the procedure. [ 79 ]

Who to contact?

Treatment appendicitis

The goal of non-operative management (NOM) is to allow patients to avoid surgery by using antibiotics.[ 80 ] Early studies in the 1950s reported successful treatment of acute appendicitis with antibiotics alone and recommended treatment for appendicitis with symptoms lasting less than 24 hours.[ 81 ],[ 82 ] In recent years, there has been renewed interest in NOM of uncomplicated acute appendicitis, with several studies reporting successful treatment of approximately 65% of cases using antibiotics alone. However, studies such as APPAC, ACTUAA, and meta-analyses have shown mixed results, with short- and long-term NOM failure rates ranging from 11.9% to 39.1%. [ 83 ] Furthermore, studies on the use of NOM in complicated appendicitis are limited but have shown that although it may be successful, it is associated with increased readmission rates and longer hospital stays. [ 84 ], [ 85 ]

Treatment of acute appendicitis consists of removing the inflamed appendix; since mortality increases with delay in treatment, a 10% negative appendectomy rate is considered acceptable. The surgeon usually removes the appendix even if it is perforated. Sometimes it is difficult to determine the location of the appendix: in these cases, the appendix is usually located behind the cecum or ileum, or the mesentery of the right flank of the colon.

Contraindications to appendectomy include inflammatory bowel disease involving the cecum. However, in cases of terminal ileitis with an intact cecum, the appendix should be removed.

Removal of the appendix should be preceded by intravenous antibiotics. Third-generation cephalosporins are preferred. In uncomplicated appendicitis, further antibiotics are not required. If perforation occurs, antibiotic therapy should be continued until the patient's temperature and white blood cell count return to normal (approximately 5 days). If surgery is not possible, antibiotics, although not a treatment, significantly improve survival. Without surgery or antibiotic therapy, mortality reaches more than 50%.

In the emergency department, the patient should be kept on no oral fluids (NPO) and hydrated intravenously with crystalloids, and antibiotics should be given intravenously as directed by the surgeon. Consent is the responsibility of the surgeon. The gold standard treatment for acute appendicitis is appendectomy. Laparoscopic appendectomy is preferred over the open approach. Most uncomplicated appendectomies are performed laparoscopically. Several studies have compared the outcomes of a laparoscopic appendectomy group with patients who underwent open appendectomy. The results showed a lower rate of wound infection, reduced need for postoperative analgesics, and a shorter postoperative hospital stay in the former group. The main disadvantage of laparoscopic appendectomy is the longer operative time.[ 86 ]

Operation time

A recent retrospective study found no significant difference in complications between early (<12 hours after presentation) and late (12–24 hours) appendectomy.[ 87 ] However, this does not take into account the actual time from symptom onset to presentation, which may influence the perforation rate.[ 88 ] After the first 36 hours from symptom onset, the average perforation rate is 16% to 36%, and the risk of perforation is 5% for every subsequent 12 hours.[ 89 ] Therefore, once the diagnosis is made, appendectomy should be performed without unnecessary delay.

Laparoscopic appendectomy

In cases of abscess or advanced infection, an open approach may be necessary. The laparoscopic approach offers less pain, a quicker recovery, and the ability to explore a larger portion of the abdomen through small incisions. Situations where there is a known abscess of a perforated appendix may require a percutaneous drainage procedure, usually performed by an interventional radiologist. This stabilizes the patient and allows time for the inflammation to subside, allowing a less complex laparoscopic appendectomy to be performed at a later date. Practitioners also prescribe broad-spectrum antibiotics to patients. There is some controversy regarding the preoperative use of antibiotics in uncomplicated appendicitis. Some surgeons believe that routine antibiotic use is inappropriate in these cases, while others prescribe them routinely.

In patients with appendiceal abscess, some surgeons continue antibiotics for several weeks and then perform an elective appendectomy. In the case of a ruptured appendix, the procedure can be performed laparoscopically, but extensive irrigation of the abdomen and pelvis is necessary. In addition, trocar sites may have to be left open. A significant number of patients with suspected acute appendicitis can be treated without complications using the laparoscopic approach. However, several factors predict the demand for conversion to an open approach. The only preoperative independent factor predicting conversion to laparoscopic appendectomy is the presence of comorbidities. Moreover, several intraoperative findings, including the presence of periappendiceal abscess and diffuse peritonitis, are independent predictors of not only a higher conversion rate but also a significant increase in postoperative complications.[ 90 ]

Open appendectomy

Although laparoscopic appendectomy is widely used as the preferred surgical treatment for acute appendicitis in many centers, open appendectomy may still be chosen as a practical option, especially in the treatment of complicated appendicitis with cellulitis and in patients who have undergone a surgical conversion from the laparoscopic approach mainly because of potential problems associated with poor visibility.

Alternative surgical approaches

Recently, several other alternative surgical approaches have been introduced including natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) and single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS). The idea of using a flexible endoscope to enter the gastrointestinal or vaginal tract and then transecting the said organ to enter the abdominal cavity is an interesting alternative for patients who are sensitive to the cosmetic aspects of the procedures. It was later tested in a successful transgastric appendectomy in a group of ten Indian patients. The main potential advantages of appendectomy by NOTES are the absence of scarring and limitation of postoperative pain. Given the limited number of patients undergoing appendectomy by NOTES, a detailed comparison of postoperative outcomes is not yet possible. Therefore, the main drawback of using this technique is the need to combine it with a laparoscopic approach to ensure adequate retraction during the procedure and to confirm closure of the entry site. [ 91 ], [ 92 ], [ 93 ] As a surgical technique, SILS for appendectomy is performed through an umbilical incision or a pre-existing abdominal scar. Potential benefits of SILS include reduced postoperative pain, postprocedural wound complications, and resulting shorter periods of sick leave. [ 94 ] However, up to 40% of patients still convert to traditional laparoscopy at some point during the procedure. The main disadvantage of SILS for appendectomy is the higher long-term complication associated with incisional hernia.

In case of detection of a large inflammatory space-occupying lesion involving the appendix, distal ileum and cecum, resection of the entire lesion and ileostomy are preferable.

In advanced cases, when a pericolic abscess has already formed, the latter is drained with a tube inserted percutaneously under ultrasound control or by open surgery (with subsequent delayed removal of the appendix). Meckel's diverticulum is removed in parallel with the removal of the appendix, but only if the inflammation around the appendix does not interfere with this procedure.

More information of the treatment

Forecast

With timely surgical intervention, the mortality rate is less than 1%, and recovery is usually rapid and complete. In case of complications (perforation and development of abscess or peritonitis), the prognosis is worse: repeated operations and prolonged recovery are possible.