Medical expert of the article

New publications

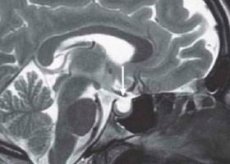

Empty saddle syndrome.

Last reviewed: 04.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

The phrase "empty sella turcica" (ETS) entered medical practice in 1951. After anatomical work, it was proposed by S. Busch, who studied autopsy material from 788 patients who died from diseases not associated with pituitary pathology. In 40 cases (34 women), a combination of almost complete absence of the sella turcica diaphragm with flattening of the pituitary gland in the form of a thin layer of tissue at its bottom was found. In this case, the sella was empty. Similar pathology had been described earlier by other anatomists, but Busch was the first to associate a partially empty sella turcica with diaphragmatic insufficiency. His observations were confirmed by later studies. In the literature, this phrase denotes various nosological forms, the common feature of which is the expansion of the subarachnoid space into the intrasellar region. The sella turcica is usually enlarged.

Causes Empty Turkish saddle syndrome.

The cause and pathogenesis of empty sella turcica are not completely clear. Empty sella turcica that develops after radiation or surgical treatment is secondary, while that which occurs without prior intervention in the pituitary gland is primary. The clinical manifestations of secondary empty sella turcica are determined by the underlying disease and complications of the therapy used. This chapter is devoted to the problem of primary empty sella turcica. It is believed that for the development of an "empty sella turcica" it is necessary to have an insufficiency of its diaphragm, i.e., a thickened protrusion of the dura mater that forms the roof of the sella turcica and closes the exit from it. The diaphragm separates the sella cavity from the subarachnoid space, excluding only the opening through which the pituitary stalk passes. The attachment of the diaphragm, its thickness, and the nature of the opening in it are subject to significant anatomical variations.

The line of its attachment to the back of the sella and its tubercle may be lowered, the overall surface is uniformly thinned, and the opening is widened due to the almost complete reduction of the diaphragm, which remains as a thin (2 mm) rim along the periphery. The resulting insufficiency leads to the spread of the subarachnoid space into the intrasellar region and to the emergence of the ability of the cerebrospinal fluid pulsation to directly affect the pituitary gland, which may lead to a decrease in its volume.

All variants of congenital pathology of the diaphragm structure cause its absolute or relative insufficiency, which is a necessary prerequisite for the development of empty sella syndrome. Other factors only predispose to the following changes:

- increased pressure in the suprasellar subarachnoid space, which, through an incomplete diaphragm, increases the impact on the pituitary gland (in cases of intracranial hypertension, hypertension, hydrocephalus, intracranial tumors);

- a decrease in the size of the pituitary gland and a violation of the volumetric relationships between it and the sella turcica, with a violation of the blood supply and pituitary infarction or adenoma (in diabetes mellitus, head injuries, meningitis, sinus thrombosis) as a result of physiological involution of the pituitary gland (during pregnancy - during this period, the volume of the pituitary gland can double, and in women who have given birth to many children it becomes even larger in size, since after childbirth it does not return to its original volume following the onset of menopause, when the volume of the pituitary gland decreases - such involution can be observed in patients with primary hypofunction of the peripheral endocrine glands, in which there is an increase in the secretion of tropic hormones and pituitary hyperplasia, and the beginning of replacement therapy leads to involution of the pituitary gland and the development of an empty sella turcica; a similar mechanism has been described after taking oral contraceptives);

- to one of the rare variants of the development of an empty sella turcica - a rupture of the intrasellar cistern containing fluid.

Thus, an empty sella turcica is a polyetiological syndrome, the main cause of which is an incomplete diaphragm of the sella turcica.

[ 1 ]

[ 1 ]

Symptoms Empty Turkish saddle syndrome.

An empty sella turcica is often asymptomatic and is accidentally detected during an X-ray examination. An "empty sella turcica" is found mainly in women (80%), more often after 40 years of age, multiparous. About 75% of patients are obese. Clinical signs are varied. Headache occurs in 70% of patients, which is the reason for an initial skull X-ray, which in 39% of cases demonstrates an altered sella turcica and leads to further more detailed examination. Headache varies widely in localization and severity - from mild, periodic, to unbearable, almost constant.

Decreased visual acuity, generalized narrowing of its peripheral fields, and bitemporal hemianopsia are possible. Edema of the papilla of the optic nerve is observed rarely, but its descriptions are found in the literature.

Rhinorrhea is a rare complication associated with rupture of the sella turcica floor by pulsating cerebrospinal fluid. The resulting connection between the suprasellar subarachnoid space and the sphenoid sinus increases the risk of meningitis. The occurrence of rhinorrhea requires surgical intervention, such as muscle tamponade of the sella turcica.

Endocrine disorders with an empty sella turcica are manifested in changes in the tropic functions of the pituitary gland. Studies using sensitive radioimmune methods and stimulation tests have revealed a high percentage of hormone secretion disorders (subclinical forms). Thus, K. Brismer et al. found that 8 of 13 patients had a reduced response to somatotropic hormone secretion to stimulation by insulin hypoglycemia, and when studying the pituitary-adrenal cortex axis, cortisol secretion after intravenous administration of ACTH changed inadequately in 2 of 16 patients; the response to metyrapone was normal in all patients examined. In contrast to these data, Faglia et al. (1973) observed an inadequate release of corticotropin to various stimuli (hypoglycemia, lysine vasopressin) in all patients examined. TSH and GT reserves were also studied using TRH and RG, respectively. The tests showed a number of changes. The nature of these disturbances is still unclear.

There are more and more papers describing hypersecretion of tropic hormones in combination with an empty sella turcica. The first of these was information about a patient with acromegaly and elevated levels of somatotropic hormone. JN Dominique et al. reported an empty sella turcica in 10% of patients with acromegaly. Usually, these patients also have a pituitary adenoma. Primary empty sella turcica develops as a result of necrosis and involution of adenomas, and adenomatous remnants continue to hypersecrete somatotropic hormone.

The most common symptom of the "empty sella turcica" syndrome is an increase in prolactin. Its growth is reported in 12-17% of patients. As in cases of STH hypersecretion, hyperprolactinemia and an empty sella turcica are often associated with the presence of adenomas. An analysis of observations shows that adenomas are found during surgery in 73% of patients with an empty sella turcica and hyperprolactinemia.

There is a description of the primary "empty sella turcica" in patients with ACTH hypersecretion. Most often these are cases of Itsenko-Cushing's disease with pituitary microadenoma. However, there is a known case of a patient with Addison's disease, in whom prolonged stimulation of corticotrophs due to adrenal insufficiency led to an ACTH-secreting adenoma and an empty sella turcica. Of interest is the description of 2 patients with an empty sella turcica and ACTH hypersecretion with normal cortisol levels. The authors suggest the production of an ACTH peptide with low biological activity and subsequent infarction of hyperplastic corticotrophs with the formation of an empty sella turcica. A number of authors provide examples of isolated ACTH insufficiency and an empty sella turcica, a combination of an empty sella turcica and adrenal carcinoma.

Thus, endocrine dysfunctions in the empty sella syndrome are extremely diverse. Both hyper- and hyposecretion of tropic hormones are encountered. Disorders range from subclinical forms detected by stimulation tests to pronounced panhypopituitarism. The variability of endocrine function changes corresponds to the breadth of etiologic factors and pathogenesis of the formation of the primary empty sella turcica.

Diagnostics Empty Turkish saddle syndrome.

The diagnosis of empty sella syndrome is usually established during the examination for a pituitary tumor. It should be emphasized that the presence of neuroradiological data indicating enlargement and destruction of the sella turcica does not necessarily indicate a pituitary tumor. The frequency of primary intrasellar pituitary tumors and empty sella syndrome in these cases was the same, 36 and 33%, respectively.

The most reliable methods for diagnosing an empty sella turcica are pneumoencephalography and computed tomography, especially in combination with the introduction of contrast agents intravenously or directly into the cerebrospinal fluid. However, signs characteristic of the empty sella turcica syndrome can be detected even on conventional X-ray and tomograms. These are the localization of changes below the diaphragm of the sella turcica, the symmetrical location of its bottom in the frontal projection, the "closed" shape of the sella, an increase mainly in the vertical size, the absence of signs of thinning and erosion of the cortical layer, a two-contour bottom on the sagittal image, with the lower line thick and clear, and the upper one blurred.

Thus, the presence of an "empty sella turcica" with its characteristic enlargement should be assumed in patients with minimal clinical symptoms and unchanged endocrine function. In these cases, there is no need to perform pneumoencephalography; the patient should simply be observed. It should be emphasized that an empty sella turcica, accompanied by an increase in its size, is often observed with an erroneous diagnosis of pituitary adenoma. However, the presence of an "empty sella turcica" does not exclude a pituitary tumor. In this case, differential diagnostics is aimed at determining the hyperproduction of hormones.

Of the radiological methods for establishing a diagnosis, the most informative is the combination of pneumoencephalography and polytomographic studies.

What do need to examine?

How to examine?

Who to contact?

Treatment Empty Turkish saddle syndrome.

There is no specific therapy for an empty sella turcica. Although the combination with an empty sella turcica does not affect the tumor treatment plan, it is important for the neurosurgeon to be aware of its coexistence, since in these cases the risk of developing postoperative meningitis increases.

Prevention

Prevention of an empty sella turcica includes the prevention of injuries, inflammatory diseases, including intrauterine ones, as well as thrombosis and tumors of the brain and pituitary gland.

Forecast

Empty sella syndrome has a different prognosis. It depends on the nature and course of concomitant diseases of the brain and pituitary gland.