Medical expert of the article

New publications

Movement coordination study

Last reviewed: 04.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Disorders of movement coordination are designated by the term "ataxia". Ataxia is a lack of coordination between different muscle groups, leading to a violation of the accuracy, proportionality, rhythm, speed and amplitude of voluntary movements, as well as to a violation of the ability to maintain balance. Disorders of movement coordination can be caused by damage to the cerebellum and its connections, disorders of deep sensitivity; asymmetry of vestibular influences. Accordingly, a distinction is made between cerebellar, sensory and vestibular ataxia.

Cerebellar ataxia

The cerebellar hemispheres control the ipsilateral limbs and are primarily responsible for the coordination, smoothness, and precision of movements in them, especially in the arms. The cerebellar vermis controls gait and coordination of trunk movements to a greater extent. Cerebellar ataxia is divided into static-locomotor and dynamic. Static-locomotor ataxia manifests itself mainly during standing, walking, and movements of the trunk and proximal parts of the limbs. It is more typical for damage to the cerebellar vermis. Dynamic ataxia manifests itself during voluntary movements of the limbs, mainly their distal parts, it is typical for damage to the cerebellar hemispheres and occurs on the affected side. Cerebellar ataxia is especially noticeable at the beginning and end of movements. The clinical manifestations of cerebellar ataxia are as follows.

- Terminal (noticeable at the end of the movement) dysmetria (discrepancy between the degree of muscle contraction and that required for precise execution of the movement; movements are usually too sweeping - hypermetria).

- Intention tremor (shaking that occurs in a moving limb as it approaches a target).

Sensory ataxia develops with dysfunction of the deep muscular-articular sensitivity pathways, more often with pathology of the posterior funiculi of the spinal cord, less often - with lesions of the peripheral nerves, posterior spinal roots, medial loop in the brainstem or thalamus. The lack of information about the position of the body in space causes a violation of reverse afferentation and ataxia.

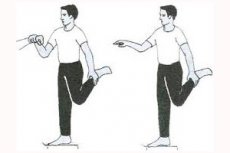

To detect sensory ataxia, dysmetria tests are used (finger-nose and heel-knee, tests for tracing a drawn circle with a finger, "drawing" an eight in the air); adiadochokinesis (pronation and supination of the hand, flexion and extension of the fingers). The standing and walking functions are also checked. All these tests are asked to be performed with closed and open eyes. Sensory ataxia decreases when visual control is turned on and increases when the eyes are closed. Intention tremor is not characteristic of sensory ataxia.

In sensory ataxia, "postural fixation defects" may occur: for example, when visual control is switched off, a patient holding his arms in a horizontal position will experience slow movement of the arms in different directions, as well as involuntary movements in the hands and fingers, reminiscent of athetosis. It is easier to hold the limbs in extreme flexion or extension positions than in average positions.

Sensory ataxia with isolated damage to the spinocerebellar tracts occurs rarely and is not accompanied by a disturbance of deep sensitivity (since these tracts, although they carry impulses from the proprioceptors of muscles, tendons and ligaments, are not related to the conduction of signals that are projected into the postcentral gyrus and create a sense of the position and movement of the limbs).

Sensory ataxia with damage to the deep sensory pathways in the brainstem and thalamus is detected on the side opposite the lesion (with localization of the lesion in the caudal parts of the brainstem, in the area of the crossing of the medial loop, ataxia can be bilateral).

[ 1 ], [ 2 ], [ 3 ], [ 4 ], [ 5 ], [ 6 ]

[ 1 ], [ 2 ], [ 3 ], [ 4 ], [ 5 ], [ 6 ]

Standing function

A person's ability to maintain an upright body position depends on sufficient muscle strength, the ability to receive information about body posture (feedback), and the ability to instantly and accurately compensate for those deviations of the trunk that threaten balance. The patient is asked to stand as he usually stands, that is, to take his natural posture in a standing position. The distance between the feet, which he involuntarily chose to maintain balance, is assessed. The patient is asked to stand up straight, put his feet together (heels and toes together), and look straight ahead. The doctor should stand next to the patient and be ready to support him at any time. Pay attention to whether the patient deviates to one side or another and whether instability increases when closing the eyes.

A patient who is unable to stand in a feet-together position with eyes open is likely to have a cerebellar pathology. Such patients walk with their legs wide apart, are unsteady when walking, and have difficulty maintaining balance without support not only when standing and walking, but also when sitting.

Romberg's symptom is the patient's inability to maintain balance in a standing position with the feet tightly together and the eyes closed. This symptom was first described in patients with tabes dorsalis, i.e., with damage to the posterior funiculi of the spinal cord. Instability in this position with the eyes closed is typical of sensory ataxia. In patients with cerebellar damage, instability in the Romberg pose is also detected with the eyes open.

Gait

Gait analysis is very important for diagnosing diseases of the nervous system. It should be remembered that balance disorders during walking can be masked by various compensatory techniques. In addition, gait disorders can be caused not by neurological, but by other pathologies (for example, joint damage).

Gait is best assessed when the patient is unaware that he or she is being observed: for example, when entering a doctor's office. The gait of a healthy person is fast, springy, light, and energetic, and maintaining balance while walking does not require special attention or effort. When walking, the arms are slightly bent at the elbows (palms facing the hips) and the movements are performed in time with the steps. Additional tests include checking the following types of walking: walking at a normal pace around the room; walking "on the heels" and "on the toes"; "tandem" walking (along a ruler, heel to toe). When conducting additional tests, it is necessary to rely on common sense and offer the patient only those tasks that he or she can actually perform at least partially.

The patient is asked to walk quickly across the room. Attention is paid to the posture while walking; the effort required to initiate and stop walking; the length of the step; the rhythm of walking; the presence of normal associated arm movements; involuntary movements. An assessment is made of how wide the patient places his legs while walking, whether he lifts his heels off the floor, and whether he drags one leg. The patient is asked to turn while walking and attention is paid to how easy it is for him to turn; whether he loses his balance; how many steps he must take to turn 360° around his axis (normally, such a turn is completed in one or two steps). Then the subject is asked to walk first on his heels, and then on his toes. An assessment is made of whether he lifts his heels/toes off the floor. The heel walking test is especially important, since dorsiflexion of the foot is impaired in many neurological diseases. The patient is observed performing the task of walking along an imaginary straight line so that the heel of the stepping foot is directly in front of the toes of the other foot (tandem walking). Tandem walking is a test that is more sensitive to balance disturbances than the Romberg test. If the patient performs this test well, other tests for upright posture stability and truncal ataxia are likely to be negative.

Gait disturbances occur in a variety of neurological diseases, as well as in muscular and orthopedic pathologies. The nature of the disturbances depends on the underlying disease.

- Cerebellar gait: when walking, the patient places his legs wide apart; is unstable in standing and sitting positions; has different step lengths; deviates to the side (in case of unilateral cerebellar damage - to the side of the lesion). Cerebellar gait is often described as "unsteady" or "drunk gait", it is observed in multiple sclerosis, cerebellar tumor, cerebellar hemorrhage or infarction, cerebellar degeneration.

- The gait in posterior cord sensory ataxia (the "tabetic" gait) is characterized by marked instability when standing and walking, despite good strength in the legs. Leg movements are jerky and abrupt; when walking, the different length and height of the step are noticeable. The patient stares at the road in front of him (his gaze is "riveted" to the floor or ground). Loss of muscle-joint feeling and vibration sensitivity in the legs is characteristic. In the Romberg position with closed eyes, the patient falls. Tabetic gait, in addition to tabes dorsalis, is observed in multiple sclerosis, compression of the posterior cords of the spinal cord (for example, by a tumor), funicular myelosis.

- Hemiplegic gait is observed in patients with spastic hemiparesis or hemiplegia. The patient "dragging" a straightened paralyzed leg (there is no flexion in the hip, knee, ankle joints), its foot is rotated inward, and the outer edge touches the floor. With each step, the paralyzed leg describes a semicircle, lagging behind the healthy leg. The arm is bent and brought to the body.

- Paraplegic spastic gait is slow, with small steps. The toes touch the floor, the legs are difficult to lift off the floor when walking, they "cross" due to increased tone of the adductor muscles and do not bend well at the knee joints due to increased tone of the extensor muscles. It is observed in bilateral lesions of the pyramidal systems (in multiple sclerosis, ALS, long-term compression of the spinal cord, etc.).

- Parkinsonian gait is shuffling, with small steps, propulsions are typical (the patient starts moving faster and faster while walking, as if catching up with his center of gravity, and cannot stop), difficulties in initiating and completing walking. The body is tilted forward while walking, the arms are bent at the elbows and pressed to the body, and are motionless while walking (acheirokinesis). If a standing patient is lightly pushed in the chest, he begins to move backwards (retropulsion). In order to turn around his axis, the patient needs to take up to 20 small steps. When walking, "freezing" in the most uncomfortable position may be observed.

- Steppage (cock gait, stamping gait) is observed when dorsiflexion of the foot is impaired. The toe of the hanging foot touches the floor when walking, as a result of which the patient is forced to lift the leg high and throw it forward while walking, while slapping the front part of the foot on the floor. The steps are of equal length. Unilateral steppage is observed when the common peroneal nerve is affected, bilateral - with motor polyneuropathy, both congenital (Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease) and acquired.

- The "duck" gait is characterized by pelvic rocking and swaying from one leg to the other. It is observed with bilateral weakness of the pelvic girdle muscles, primarily the gluteus medius. With weakness of the hip abductor muscles, the pelvis on the opposite side drops during the standing phase on the affected leg. Weakness of both gluteus medius muscles leads to bilateral disruption of the fixation of the hip of the supporting leg, the pelvis drops and rises excessively during walking, the torso "rolls" from side to side. Due to weakness of other proximal leg muscles, patients experience difficulty climbing stairs and getting up from a chair. Getting up from a sitting position is done with the help of the arms, with the patient resting his hands on the thigh or knee and only in this way can he straighten the torso. Most often, this type of gait is observed in progressive muscular dystrophies (PMD) and other myopathies, as well as in congenital hip dislocation.

- Dystonic gait is observed in patients with hyperkinesis ( chorea, athetosis, muscular dystonia). As a result of involuntary movements, the legs move slowly and awkwardly, involuntary movements are observed in the arms and torso. Such gait is called "dancing", "twitching".

- Antalgic gait is a reaction to pain: the patient spares the sore leg, moving it very carefully and trying to load mainly the second, healthy leg.

- Hysterical gait can be very different, but does not have those typical signs that are characteristic of certain diseases. The patient may not lift his leg off the floor at all, dragging it, may demonstrate pushing off the floor (as when skating) or may sway sharply from side to side, avoiding, however, falls, etc.

Involuntary pathological movements

Involuntary violent movements that interfere with the performance of voluntary motor acts are designated by the term "hyperkinesis". If a patient has hyperkinesis, it is necessary to assess its rhythm, stereotypy or unpredictability, to find out in what positions they are most pronounced, with what other neurological symptoms they are combined. When collecting anamnesis from patients with involuntary movements, it is necessary to find out the presence of hyperkinesis in other family members, the effect of alcohol on the intensity of hyperkinesis (this is important only in relation to tremor), medications used previously or at the time of examination.

- Tremor is a rhythmic or partially rhythmic shaking of a body part. Tremor is most often observed in the hands (in the wrists), but it can occur in any part of the body (head, lips, chin, torso, etc.); tremor of the vocal cords is possible. Tremor occurs as a result of alternative contraction of oppositely acting agonist and antagonist muscles.

Types of tremor are distinguished by localization, amplitude, and conditions of occurrence.

- Low-frequency slow tremor of rest (occurring in a resting limb and decreasing/disappearing with voluntary movement) is typical of Parkinson's disease. Tremor usually occurs on one side, but later becomes bilateral. The most typical (although not obligatory) movements are "rolling pills", "counting coins", amplitude and localization of muscle contractions. Therefore, when characterizing clinical forms, localized and generalized; unilateral or bilateral; synchronous and asynchronous; rhythmic and arrhythmic myoclonus are distinguished. Familial degenerative diseases, in the clinical picture of which myoclonus is the main symptom, include Davidenkov's familial myoclonus, Tkachev's familial localized myoclonus, Lenoble-Aubino familial nystagmus-myoclonus, and Friedreich's multiple paramyoclonus. Rhythmic myoclonus (myorhythmia) is a special local form of myoclonus, characterized by stereotypy and rhythm. Hyperkinesis is limited to the involvement of the soft palate (velopalatine myoclonus, velopalatine "nystagmus"), individual muscles of the tongue, neck, and, less frequently, limbs. Symptomatic forms of myoclonus occur in neuroinfections and dysmetabolic and toxic encephalopathies.

- Asterixis (sometimes called "negative myoclonus") is a sudden, arrhythmic "fluttering" oscillatory movement of the limbs at the wrist or, less commonly, ankle joints. Asterixis is caused by variability in postural tone and short-term atony of the muscles that maintain posture. It is most often bilateral, but occurs asynchronously on both sides. Asterixis most often occurs with metabolic (renal, liver ) encephalopathy, and is also possible with hepatocerebral dystrophy.

- Tics are fast, repetitive, arrhythmic, but stereotypical movements in individual muscle groups that occur as a result of the simultaneous activation of agonist and antagonist muscles. The movements are coordinated and resemble a caricature of a normal motor act. Any attempt to suppress them by willpower leads to increased tension and anxiety (although a tic can be voluntarily suppressed). Performing a desired motor reaction provides relief. Imitation of a tic is possible. Tics intensify with emotional stimuli (anxiety, fear), and decrease with concentration, after drinking alcohol, or during pleasant entertainment. Tics may appear in different parts of the body or be limited to one part. According to the structure of hyperkinesis, simple and complex tics are distinguished, according to localization - focal (in the muscles of the face, head, limbs, trunk) and generalized. Generalized complex tics can outwardly resemble a purposeful motor act in complexity. Sometimes the movements resemble myoclonus or chorea, but, unlike them, tics make normal movements in the affected part of the body less difficult. In addition to motor tics, there are also phonetic tics: simple - with elementary vocalization - and complex, when the patient shouts out whole words, sometimes curses (coprolalia). The frequency of tic localization decreases in the direction from the head to the feet. The most common tic is blinking. Generalized tic or syndrome (disease) of Gilles de la Tourette is a hereditary disease transmitted by an autosomal dominant type. Most often begins at the age of 7-10 years. It is characterized by a combination of generalized motor and phonetic tics (screaming, coprolalia, etc.), as well as psychomotor (obsessive stereotypical actions), emotional (suspiciousness, anxiety, fear) and personality (isolation, shyness, lack of self-confidence) changes.

- Dystonic hyperkinesis is an involuntary, prolonged, violent movement that can involve muscle groups of any size. It is slow, constant, or occurs periodically during specific motor acts; it distorts the normal position of the limb, head, and torso in the form of certain poses. In severe cases, fixed poses and secondary contractures may occur. Dystonias can be focal or involve the entire body (torsion dystonia). The most common types of focal muscular dystonia are blepharospasm (involuntary closing/squinting of the eyes); oromandibular dystonia (involuntary movements and spasms of the facial and tongue muscles); spasmodic torticollis (tonic, clonic, or tonic-clonic contraction of the neck muscles, leading to involuntary tilts and turns of the head); writer's cramp.

- Athetosis is a slow dystonic hyperkinesis, the "creeping" spread of which in the distal parts of the limbs gives involuntary movements a worm-like character, and in the proximal parts of the limbs - a serpentine character. The movements are involuntary, slow, occur mainly in the fingers and toes, tongue and replace each other in a disorderly sequence. The movements are smooth and slower compared to choreic. The poses are not fixed, but gradually pass from one to another ("mobile spasm"). In more pronounced cases, the proximal muscles of the limbs, the muscles of the neck and face are also involved in hyperkinesis. Athetosis intensifies with voluntary movements and emotional stress, decreases in certain poses (in particular, on the stomach), during sleep. Unilateral or bilateral athetosis in adults may occur in hereditary diseases with damage to the extrapyramidal nervous system ( Huntington's chorea, hepatocerebral dystrophy); in vascular lesions of the brain. In children, athetosis most often develops as a result of brain damage in the perinatal period as a result of intrauterine infections, birth trauma, hypoxia, fetal asphyxia, hemorrhage, intoxication, hemolytic disease.