Medical expert of the article

New publications

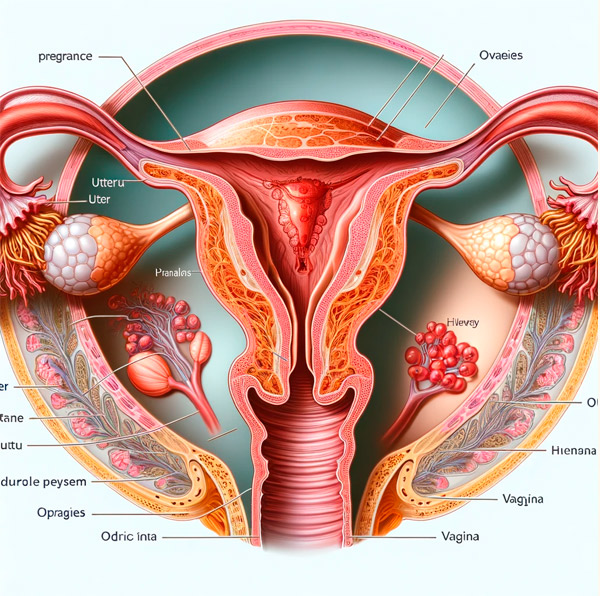

Bleeding in the II and III trimesters of pregnancy

Last reviewed: 04.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Bleeding in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy occurs in 6% of all pregnancies and has a different etiology from bleeding in the first trimester. [ 1 ] In the vast majority of cases, antepartum bleeding is vaginal and obvious; [ 2 ] however, in rare cases it may be located in the uterine cavity, intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal space.

The most common causes of bleeding are placenta previa and premature separation of a normally located placenta. In cases of severe antepartum hemorrhage, complications include preterm labor, cesarean section, blood transfusion, coagulopathy, [ 3 ] hemodynamic instability, multiple organ failure, salpingectomy/oophorectomy, postpartum hysterectomy, and in some cases, perinatal or maternal death.

Placenta previa is an abnormal attachment of the placenta in the uterus, its location in the area of the lower uterine segment, above the internal os, which leads to its partial or complete overlap and the location of the placenta below the presenting part of the fetus, i.e. in the path of the fetus being born.

Epidemiology

The incidence of placenta previa in relation to the total number of pregnancies is 0.2–0.6%. In approximately 80% of cases, this pathology is observed in multiparous women (more than 2 births in the anamnesis). Maternal morbidity is 23%, premature births develop in 20% of cases. Maternal mortality in placenta previa ranges from 0 to 0.9%. The main causes of death are shock and hemorrhage. Perinatal mortality is high and varies from 17 to 26%. [ 4 ], [ 5 ]

Causes bleeding in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy

Placenta previa

Placenta previa occurs when the placenta partially or completely covers the internal cervical os. This contrasts with a low-lying placenta, in which the placenta lies within 2 cm of but does not extend beyond the internal cervical os. The etiology of placenta previa is unknown. Risk factors include smoking, advanced maternal age, multiple gestation, in vitro fertilization, multiple gestation, Asian race, previous endometrial damage, previous pregnancy loss or spontaneous abortion, previous cesarean section, and previous placenta previa.[ 6 ],[ 7 ] These risk factors suggest that the pathogenesis may be due to endometrial damage or suboptimal endometrial perfusion in other areas of the uterus. The incidence of placenta previa at term is approximately 1 in 200 pregnancies; The incidence is higher in early pregnancy, but many placenta previas resolve as the lower uterine segment matures and the placenta expands preferentially toward the more vascularized areas of the uterus.

Abnormal location of the placenta

Anomalously adherent placenta occurs when the placenta is abnormally implanted into the uterine myometrium, rather than the normal implantation of the placenta into the basal decidua of the uterus.[ 8 ] Invasive placentation results from the absence of the decidua basalis and incomplete development or damage to the Nitabuch's layer. The incidence of anomalously adherent placenta ranges from 1 in 300 to 1 in 500 pregnancies. The most significant risk factor is placenta previa in the context of one or more prior cesarean sections or other uterine surgeries. With one prior cesarean section and placenta previa, the risk is 11%; with three or more prior cesarean sections and placenta previa, the risk exceeds 60%. [ 9 ] Other common risk factors include advanced maternal age, high parity, pregnancy in a cesarean section scar, and in vitro fertilization.[ 10 ], [ 11 ], [ 12 ]

Placental abruption

Placental abruption occurs when the placenta prematurely separates from the implantation site. Traditionally viewed as an “acute” event, often resulting from physical abdominal trauma, current evidence suggests that placental abruption is often chronic.[ 13 ],[ 14 ] However, acute placental abruptions still occur. Abruptions may be either overt, with vaginal bleeding as an early symptom, or occult, with blood remaining in the uterus. Pathophysiological mechanisms involved in abruption include uteroplacental insufficiency, ischemia, placental infarction, and chronic hypoxia.[ 15 ],[ 16 ] Very rarely, fetal abruption may occur following diagnostic and therapeutic intrauterine procedures in the second trimester (amniocentesis, cardiovascular surgery, fetal surgery). Abruption affects approximately 1% of pregnancies but is associated with a recurrence risk of approximately 10–15% for one previous abruption, 20–30% after two, and ≥30% after three or more abruptions.[ 17 ],[ 18 ] Other risk factors include first trimester bleeding, hypertension, thrombophilia, illicit drug use (especially cocaine), smoking, trauma, in vitro fertilization, and premature rupture of membranes.[ 19 ],[ 20 ],[ 21 ] Pregnancies diagnosed with abruption end 3–4 weeks earlier than other pregnancies, with more than half delivering preterm. This contrasts with a preterm birth rate of 12% among unaffected pregnancies.[ 22 ],[ 23 ]

Vasa previa

Vasa previa occurs when fetal blood vessels pass within the amniotic membranes at or within 2 cm of the internal cervical os. Type I vasa previa occurs when the umbilical cord is attached to the membranes, allowing fetal vessels to pass freely within the membranes between the cord and placenta. Type II vasa previa occurs when the succenturiate lobe of the placenta and the main lobe of the placenta are connected by fetal vessels that flow freely within the membranes. Vasa previa is rare, occurring in 1 in 2,500 births. Risk factors include a resected low-lying placenta, placenta previa, and multiple gestations.

Pregnancy in a cesarean section scar

A cesarean scar pregnancy is an ectopic pregnancy implanted in a previous cesarean section (hysterotomy) scar surrounded by myometrium and connective tissue. It occurs due to a small defect in the cesarean scar resulting from poor healing and poor vascularization of the lower uterine segment with subsequent fibrosis.[ 24 ] The pathophysiology of a cesarean scar pregnancy is similar to that of an intrauterine pregnancy with an abnormally implanted placenta.[ 25 ] Cesarean scar pregnancy occurs in approximately 1 in 2,000 pregnancies and accounts for 6% of ectopic pregnancies among women who have had a previous cesarean section. Because cesarean scar pregnancy has only recently been recognized, risk factors are not yet clear; However, as with placenta accreta, the incidence appears to be correlated with the number of previous cesarean sections.

Intra-abdominal pregnancy

Intra-abdominal pregnancy is a rare form of ectopic pregnancy in which the fetus implants in the abdominal cavity or abdominal organs. It is most often due to ectopic pregnancy with tubal extrusion or rupture and secondary implantation; primary implantation in the abdominal cavity is also possible. The pregnancy may be asymptomatic or accompanied by life-threatening intra-abdominal bleeding. The incidence is difficult to determine because data are derived from case reports, but it has been reported to be 1–2 per 10,000. Risk factors include artificial insemination, in vitro fertilization, uterine surgery, and previous tubal or cornual pregnancy.[ 26 ],[ 27 ]

Uterine rupture

Uterine rupture is a complete, non-surgical disruption of all layers of the uterus. Uterine rupture can occur either in an unscarred uterus or at the site of a scar from a previous hysterotomy. The incidence of unscarred uterine rupture is approximately 1 in 20,000 deliveries in high-resource settings, but may be as high as 1 in 100 deliveries in low-resource settings, where the majority of ruptures of this type occur.[ 28 ],[ 29 ] Risk factors for uterine rupture in an unscarred uterus include a contracted pelvis, prolonged dystotic labour, multiple pregnancy, malpositioned placenta, malpresentation, use of potent uterotonic drugs possibly with pelvic disproportion, operative vaginal delivery at a high station, and congenital myometrial weakness. In high-resource settings, uterine rupture most often occurs in the context of a previous hysterotomy scar or transfundal surgery. The incidence of this event ranges from approximately 1 in 200 to 1 in 10, depending on the type of hysterotomy and the use of labor.[ 30 ],[ 31 ] Additional risk factors include the number of previous cesarean sections, an interval between births of less than 18 months, single-layer uterine closure, and open fetal surgery.[ 32 ],[ 33 ]

Forms

By degree of placenta previa:

- complete - the internal os is completely covered by the placenta;

- partial - the internal os is partially covered by the placenta;

- marginal - the edge of the placenta is located at the edge of the internal os;

- low - the placenta is implanted in the lower segment of the uterus, but its edge does not reach the internal os.

Diagnostics bleeding in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy

The medical history includes a large number of births, previous abortions, post-abortion and postpartum septic diseases, uterine fibroids, deformation of the uterine cavity (scars after cesarean section and other operations, uterine developmental anomalies), advanced age of primiparous women, pregnancy as a result of ovulation stimulation, in vitro fertilization.

Symptoms of placenta previa before the development of bleeding are extremely scanty. They note the high position of the presenting part of the fetus, its unstable position, often oblique or transverse position, breech presentation, often there are symptoms of threatened termination of pregnancy, fetal hypotrophy.

The main clinical symptom of placenta previa is bleeding, characterized by the absence of pain syndrome ("painless bleeding"), frequent recurrence and progressive anemia of the pregnant woman. Uterine bleeding with placenta previa most often develops at 28-30 weeks of pregnancy, when the preparatory activity of the lower uterine segment is most pronounced. The diagnosis of placenta previa is based on clinical data, mainly on bleeding with scarlet blood.

It is necessary to examine the cervix with vaginal speculums and perform a vaginal examination. During the examination with speculums, scarlet blood is detected from the cervical canal. During the vaginal examination, placental tissue and rough membranes are determined behind the internal os. If there are ultrasound data, a vaginal examination should not be performed.

Screening

Conducting ultrasound at 10–13, 16–24, 32–36 weeks of pregnancy. The location of the placenta is determined during each examination, starting from the 9th week of pregnancy.

What do need to examine?

How to examine?

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis should be made with the following conditions:

- premature detachment of a normally located placenta;

- rupture of the marginal sinus of the placenta;

- rupture of the umbilical cord vessels at their membrane attachment;

- uterine rupture;

- ectopia of the cervix;

- rupture of varicose veins of the vagina;

- bleeding ectopia;

- polyps;

- cervical carcinoma.

Treatment bleeding in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy

The goal of treatment is to stop bleeding.

Indications for hospitalization

Complete placenta previa even in the absence of clinical symptoms; occurrence of bloody discharge from the genital tract.

Non-drug treatment of bleeding in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy

Elimination of physical activity, bed rest, sexual abstinence.

Drug therapy for bleeding in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy

The therapy is aimed at relieving uterine excitability and strengthening the vascular wall:

- drotaverine 2% solution (2 ml intramuscularly);

- hexoprenaline sulfate (500 mcg - 1 tablet every 3 hours, then every 4-6 hours);

- fenoterol 10 ml intravenously by drip in 400 ml of 5% glucose solution;

- menadione sodium bisulfite 1% solution (1.0 v/m);

- etamsylate 12.5% solution (2.0 i/v, i/m) in [5, 9].

In premature pregnancy (up to 34 weeks), in order to prevent fetal respiratory distress syndrome, it is recommended to administer high doses of glucocorticoids - dexamethasone 8-12 mg (4 mg 2 times a day intramuscularly for 2-3 days or per os 2 mg 4 times on the 1st day, 2 mg 3 times on the 2nd day, 2 mg 2 times on the 3rd day) (see the article "Treatment of threatened premature labor").

Surgical treatment of bleeding in the II and III trimesters of pregnancy

The choice of therapy method depends on the amount of blood loss, the general condition of the pregnant woman, the type of placenta previa, the duration of pregnancy, and the position of the fetus.

In case of central placenta previa without bleeding, delivery by caesarean section at 37 weeks is indicated on a planned basis.

If bleeding amounts to 250 ml or more, regardless of the degree of placenta previa, emergency delivery by cesarean section is indicated at any stage of pregnancy.

Due to insufficient development of the decidual membrane in the lower uterine segment, dense attachment of the placenta, sometimes its true accretion, often occurs. In such cases, removal of the uterus is indicated.

In case of marginal placenta previa, expectant management can be used until spontaneous onset of labor, and early amniotomy is indicated during labor.

Patient education

The pregnant woman should be informed about the presence of placenta previa, the need for sexual rest, bed rest, and immediate hospitalization if even minor bleeding from the genital tract occurs.

Prevention

Reduction in the number of conditions that cause abnormal implantation of the fertilized egg - abortions, intrauterine interventions, inflammatory diseases of the internal genital organs.

Forecast

The prognosis for the life of the mother and fetus is ambiguous. The outcome of the disease depends on the etiological factor, the nature and severity of the bleeding, the timeliness of the diagnosis, the choice of an adequate treatment method, the condition of the pregnant woman's body, and the degree of maturity of the fetus.

Sources

- Hull AD, Resnik R. 6th ed. Saunders; Philadelphia (PA): 2009. Placenta previa, placenta accreta, abruptio placentae, and vasa previa.

- Silver RM Abnormal placement: placenta previa, vasa previa, and placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:654–668.

- Taylor V., Peacock S., Kramer M., Vaughan T. Increased risk of placenta previa among women of Asian origin. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:805–808.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Clinical Opinion Placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:430–439.

- Francois KE, Foley MR Antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage. In: Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, editors. Obstetrics: normal and problem pregnancies. 5th ed. Elsevier; Philadelphia (PA): 2007.

- Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Thom EA Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1226–1232.

- Fitzpatrick KE, Sellers S., Spark P., Kurinczuk JJ, Brocklehurst P., Knight M. Incidence and risk factors for placenta accreta/increta/percreta in the UK: a national case-control study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52893.

- Esh-Broder E., Ariel I., Abas-Bashir N., Bdolah Y., Celnikier DH Placenta accreta is associated with IVF pregnancies: a retrospective chart review. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;118:1084–1089.

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A., Cali G., Vintzileos A., Viscarello R., Al-Khan A. Cesarean scar pregnancy is a precursor of morbidly adherent placenta. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol Off J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;44:346–353.

- Pritchard JA, Mason R., Corley M., Pritchard S. Genesis of severe placental abruption. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970;108:22–27.

- Lowe TW, Cunningham FG Placental abruption. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1990;33:406–413

- Naeye RL Abruptio placentae and placenta previa: frequency, perinatal mortality, and cigarette smoking. Obstet Gynecol. 1980;55:701–704.

- Kettel LM, Branch DW, Scott JR Occult placental abruption after maternal trauma. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:449–453.

- Ananth CV, Getahun D., Peltier MR, Smulian JC Placental abruption in term and preterm gestations: evidence for heterogeneity in clinical pathways. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:785–792.

- Ananth CV, Peltier MR, Chavez MR, Kirby RS, Getahun D., Vintzileos AM Recurrence of ischemic placental disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:128–133.

- Ananth CV, Peltier MR, Kinzler WL, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM Chronic hypertension and risk of placental abruption: is the association modified by ischemic placental disease? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(273):e1–e7.

- Ananth CV, Oyelese Y., Yeo L., Pradhan A., Vintzileos AM Placental abruption in the United States, 1979 through 2001: temporal trends and potential determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:191–198.

- Ananth CV, Savitz DA, Williams MA Placental abruption and its association with hypertension and prolonged rupture of membranes: a methodological review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:309–318.

- Lucovnik M., Tul N., Verdenik I., Blickstein I. Perinatal outcomes in singleton and twin pregnancies following first-trimester bleeding. J Perinatol. 2014;34:673–676.

- Brenner B., Kupferminc M. Inherited thrombophilia and poor pregnancy outcome. Est Pr Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;17:427–439.

- Qin J., Liu X., Sheng X., Wang H., Gao S. Assisted reproductive technology and the risk of pregnancy-related complications and adverse pregnancy outcomes in singleton pregnancies: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(73–85):e6.

- Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine Consult Series. Diagnosis and management of vasa previa. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:615–9.

- Rotas MA, Haberman S., Levgur M. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1373–1381.

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A. Unforeseen consequences of the increasing rate of cesarean deliveries: early placenta accreta and cesarean scar pregnancy. A review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:14–29.

- Huang K., Song L., Wang L., Gao Z., Meng Y., Lu Y. Advanced abdominal pregnancy: an increasingly challenging clinical concern for obstetricians. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5461.

- Costa SD, Presley J., Bastert G. Advanced abdominal pregnancy (review) Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1991;46:515–525.

- Berhe Y., Wall L.L. Uterine rupture in resource-poor countries. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2014;69:695–707.

- Gibbins KJ, Weber T., Holmgren CM, Porter TF, Varner MW, Manuck TA Maternal and fetal morbidity associated with uterine rupture of the unscarred uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(382):e1–e6.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Say L., Gülmezoglu AM WHO systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity: the prevalence of uterine rupture. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112:1221–1228.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG practice bulletin no. 115: vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:450–463.

- Smith JG, Mertz HL, Merrill DC Identifying risk factors for uterine rupture. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35:85–99. viii.

[

[