Medical expert of the article

New publications

Pathogenesis of hepatitis B

Last reviewed: 07.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

In the pathogenesis of hepatitis B, several leading links in the pathogenetic chain can be identified:

- introduction of the pathogen - infection;

- fixation on the hepatocyte and penetration into the cell;

- multiplication of the virus and its “pushing out” onto the surface of the hepatocyte, as well as into the blood;

- activation of immunological reactions aimed at eliminating the pathogen;

- immune complex damage to organs and systems;

- formation of immunity, release from the pathogen, recovery.

Since infection with hepatitis B always occurs parenterally, it can be considered that the moment of infection is practically equivalent to the penetration of the virus into the blood. Attempts by some researchers to distinguish enteral and regional phases in hepatitis B are poorly substantiated. There are more grounds to believe that the virus immediately enters the liver with the blood flow.

The tropism of the hepatitis B virus to liver tissue is predetermined by the presence of a special receptor in the HBsAg - a polypeptide with a molecular weight of 31,000 Da (P31), which has albumin-binding activity. A similar albumin zone is also found on the membrane of hepatocytes in the liver of humans and chimpanzees, which essentially determines the tropism of HBV to the liver of humans and chimpanzees.

When the virus penetrates the hepatocyte, viral DNA is released, which, entering the hepatocyte nucleus and acting as a matrix for the synthesis of nucleic acids, triggers a series of sequential biological reactions, the result of which is the assembly of the nucleocapsid of the virus. The nucleocapsid migrates through the nuclear membrane into the cytoplasm, where the final assembly of Dane particles - the complete hepatitis B virus - occurs.

It should be noted, however, that when a hepatocyte is infected, the process can proceed in two ways - replicative and integrative. In the first case, a picture of acute or chronic hepatitis develops, and in the second - virus carriage.

The reasons that determine the two types of interaction between viral DNA and hepatocytes have not been precisely established. Most likely, the type of response is genetically determined.

The result of replicative interaction is the assembly of the core antigen structures (in the nucleus) and the assembly of the complete virus (in the cytoplasm), followed by the presentation of the complete virus or its antigens on the membrane or in the structure of the hepatocyte membrane.

It is generally accepted that virus replication does not result in cell damage at the hepatocyte level, since the hepatitis B virus does not have a cytopathic effect. This position cannot be considered indisputable, since it is based on experimental data that, although they indicate the absence of a cytopathic effect of the hepatitis B virus, were obtained on tissue cultures and therefore cannot be fully extrapolated to viral hepatitis B in humans. In any case, the issue of the absence of hepatocyte damage during the replicative phase requires additional study.

However, regardless of the nature of the interaction of the virus with the cell, the liver is necessarily included in the immunopathological process. In this case, the damage to hepatocytes is associated with the fact that as a result of the expression of viral antigens on the hepatocyte membrane and the release of viral antigens into free circulation, a chain of sequential cellular and humoral immune reactions is included, ultimately aimed at removing the virus from the body. This process is carried out in full compliance with the general patterns of the immune response to viral infections. To eliminate the pathogen, cellular cytotoxic reactions are included, mediated by various classes of effector cells: K cells, T cells, natural killers, macrophages. During these reactions, the infected hepatocytes are destroyed, which is accompanied by the release of viral antigens (HBcAg, HBeAg, HBsAg), which trigger the antibody genesis system, as a result of which specific antibodies accumulate in the blood, primarily to the core - anti-HBc and e-antigen - anti-HBE. Consequently, the release of the liver cell from the virus occurs in the process of its death due to the reactions of cellular cytolysis.

At the same time, specific antibodies accumulating in the blood bind the virus antigens, forming immune complexes phagocytized by macrophages and excreted by the kidneys. In this case, various immune complex lesions may occur in the form of glomerulonephritis, arteritis, arthralgia, skin rashes, etc. With the participation of specific antibodies, the body is cleansed of the pathogen and complete recovery occurs.

In accordance with the outlined concept of the pathogenesis of hepatitis B, all the diversity of clinical variants of the course of the disease is usually explained by the peculiarities of the interaction of the virus and the cooperation of immunocompetent cells, in other words, the strength of the immune response to the presence of viral antigens. According to modern concepts, the strength of the immune response is genetically determined and linked to the histocompatibility antigens of the HLA locus of the first class.

It is generally accepted that under conditions of an adequate immune response to virus antigens, acute hepatitis develops clinically with a cyclic course and complete recovery. Against the background of a decrease in the immune response to virus antigens, immune-mediated cytolysis is expressed insignificantly, therefore, there is no effective elimination of infected liver cells, which leads to mild clinical manifestations with long-term persistence of the virus and, possibly, the development of chronic hepatitis. At the same time, on the contrary, in the case of a genetically determined strong immune response and massive infection (hemotransfusion), extensive areas of liver cell damage arise, which clinically correspond to severe and malignant forms of the disease.

The presented scheme of the pathogenesis of hepatitis B is distinguished by its coherence; however, it contains a number of controversial and poorly studied points.

If we follow the concept of hepatitis B as an immunopathological disease, we could expect an increase in cellular cytotoxicity reactions with increasing severity of the disease. However, in severe forms, the indices of the cellular link of immunity are sharply reduced, including a multiple drop, compared with those in healthy children, and the K-cell cytotoxicity index. In the malignant form, during the period of development of massive liver necrosis and especially hepatic coma, a complete inability of lymphocytes to blast transformation under the influence of phytohemattlutinin, staphylococcal endotoxin and HBsAg is noted. In addition, there is no ability of leukocytes to migrate according to the leukocyte migration inhibition reaction (LMIC), and a sharp increase in the permeability of lymphocyte membranes is revealed according to the results of their studies using a fluorescent tetracycline probe.

Thus, if the fluorescence indices of lymphocytes in healthy people are 9.9±2%, and in typical hepatitis B with a benign course they increase to 22.3±2.7%, then in malignant forms the number of fluorescent lymphocytes reaches an average of 63.5±5.8%. Since an increase in the permeability of cell membranes is unambiguously assessed in the literature as a reliable indicator of their functional inferiority, it can be concluded that with hepatitis B, especially in the malignant form, there is gross damage to lymphocytes. This is also evidenced by the indices of K-cell cytotoxicity. In a severe form, on the 1-2nd week of the disease, cytotoxicity is 15.5±8.8%, and in the malignant form on the 1st week - 6.0±2.6, on the 2nd - 22.0±6.3% with a norm of 44.8±2.6%.

The presented data clearly indicate pronounced disturbances in the cellular link of immunity in patients with severe forms of hepatitis B. It is also obvious that these changes occur secondarily, as a result of damage to immunocompetent cells by toxic metabolites and, possibly, circulating immune complexes.

As studies have shown, in patients with severe forms of hepatitis B, especially in the case of the development of massive liver necrosis, the titer of HBsAg and HBeAg in the blood serum decreases and at the same time antibodies to the surface antigen begin to be detected in high titers, which is completely uncharacteristic for benign forms of the disease, in which anti-HBV appear only in the 3rd-5th months of the disease.

The rapid disappearance of hepatitis B virus antigens with the simultaneous appearance of high titers of antiviral antibodies suggests the intensive formation of immune complexes and their possible participation in the pathogenesis of the development of massive liver necrosis.

Thus, the factual materials do not allow us to interpret hepatitis B unambiguously only from the standpoint of immunopathological aggression. And the point is not only that no connection is found between the depth and prevalence of morphological changes in the liver, on the one hand, and the severity of cellular immunity factors, on the other. Theoretically, this circumstance could be explained by the late stages of the study of cellular immunity indicators, when immunocompetent cells were subjected to powerful toxic effects due to increasing functional insufficiency of the liver. Of course, it can be assumed that immune cytolysis of hepatocytes occurs at the earliest stages of the infectious process, possibly even before the appearance of clinical symptoms of severe liver damage. However, such an assumption is unlikely, since similar indicators of cellular immunity were detected in patients with the most acute (lightning) course of the disease and, in addition, during morphological examination of liver tissue, massive lymphocytic infiltration was not detected, while at the same time, continuous fields of necrotic epithelium were detected without the phenomena of resorption and lymphocytic aggression.

It is very difficult to explain the morphological picture of acute hepatitis only from the standpoint of immune cellular cytolysis, therefore, in early studies, the cytotoxic effect of the hepatitis B virus was not excluded.

Currently, this assumption has been partially confirmed by the discovery of the hepatitis B virus. As studies have shown, the frequency of detection of hepatitis D markers is directly dependent on the severity of the disease: in mild forms, they are detected in 14%, moderate - in 18%, severe - 30%, and malignant - in 52% of patients. Considering that the hepatitis D virus has a necrosogenic cytopathic effect, it can be considered established that coinfection with hepatitis B and D viruses is of great importance in the development of fulminant forms of hepatitis B.

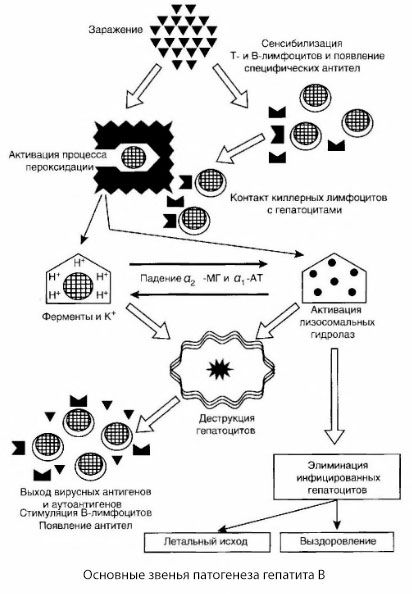

The pathogenesis of hepatitis B can be presented as follows. After the penetration of the hepatitis B virus into hepatocytes, an immunological attack on the infected hepatocytes is induced by T-killers, which secrete lymphotoxins in the direction of liver cells.

The intimate mechanisms of hepatocyte damage in hepatitis B have not yet been established. The leading role is played by activated processes of lipid peroxidation and lysosomal hydrolases. The trigger may be lymphotoxins released from effector cells upon their contact with hepatocytes, but it is possible that the virus itself may be the initiator of peroxidation processes. Subsequently, the pathological process most likely develops in the following sequence.

- Interaction of the aggression factor (lymphotoxins or virus) with biological macromolecules (possibly with components of the endoplasmic reticulum membranes capable of participating in detoxification processes, by analogy with other damaging agents, as was shown in relation to carbon tetrachloride).

- Formation of free radicals, activation of lipid peroxidation processes and increased permeability of all hepatocellular membranes (cytolysis syndrome).

- Movement of biologically active substances along the concentration gradient - loss of enzymes of various intracellular localizations, energy donors, potassium, etc. Accumulation of sodium and calcium in cells, shift in pH towards intracellular acidosis.

- Activation and release of lysosomal hydrolases (RNAse, DNAse, cathepsins, etc.) with the breakdown of liver cells and the release of autoantigens.

- Stimulation of the T- and B-immune systems with the formation of specific sensitization of T-lymphocytes to liver lipoprotein, as well as the formation of antihepatic humoral autoantibodies.

In the proposed scheme of hepatitis B pathogenesis, the triggering factor is viral antigens, whose intensive production is observed at the earliest stages of the disease and throughout the acute period, with the exception of malignant forms, in which the production of viral antigens practically ceases at the time of development of massive liver necrosis, which predetermines a rapid decrease in viral replication.

It is also obvious that viral antigens activate the T- and B-systems of immunity. During this process, a characteristic redistribution of T-lymphocyte subpopulations occurs, aimed at organizing an adequate immune response, eliminating infected hepatocytes, neutralizing viral antigens, sanogenesis and recovery.

When immunocompetent cells interact with viral antigens on hepatocyte membranes or during virus reproduction inside a hepatocyte, conditions arise for the activation of lipid peroxidation processes, which, as is known, controls the permeability of all cellular and subcellular membranes.

From this position, the occurrence of cytolysis syndrome, an increased permeability of cell membranes, which is so natural and highly characteristic of viral hepatitis, becomes understandable.

The final outcome of cytolysis syndrome may be complete uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation, leakage of cellular material, and death of the liver parenchyma.

However, in the vast majority of cases, these processes do not acquire such a fatal development. Only in malignant forms of the disease does the pathological process proceed in an avalanche-like manner and irreversibly, since massive infection, a pronounced immune process, excessive activation of peroxidation processes and lysosomal hydrodases, and autoimmune aggression phenomena occur.

The same mechanisms are observed in the favorable course of hepatitis B, with the only peculiarity that they are all realized at a qualitatively different level. Unlike cases of massive liver necrosis, in the favorable course of the disease the number of infected hepatocytes, and therefore the zone of immunopathological cytolysis is smaller, the processes of lipid peroxidation are not as significantly enhanced, the activation of acid hydrolases leads only to limited autolysis with an insignificant release of autoantigens, and therefore, without massive autoaggression, that is, all stages of pathogenesis in the favorable course are carried out within the framework of the preserved structural organization of the liver parenchyma and are restrained by defense systems (antioxidants, inhibitors, etc.) and therefore do not have such a destructive effect.

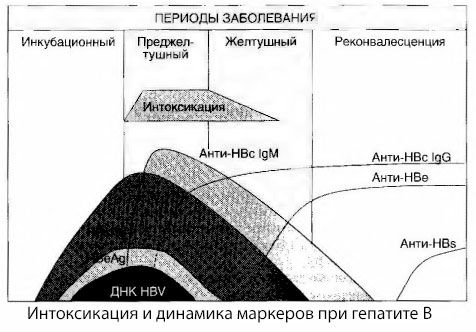

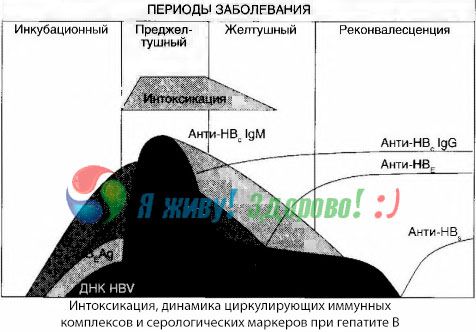

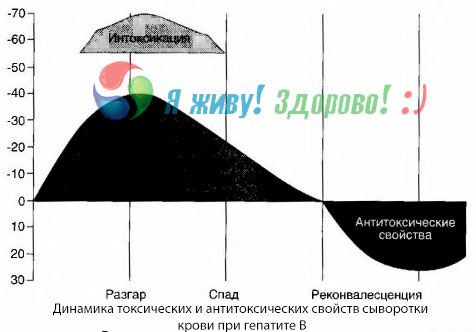

The causes of intoxication symptoms in viral hepatitis have not been fully studied. The proposal to distinguish between the so-called primary, or viral, intoxication and secondary (exchange, or metabolic) can be considered positive, although this does not reveal the intimate mechanism of the occurrence of general toxic syndrome. Firstly, hepatitis viruses do not have toxic properties, and secondly, the concentration of many metabolites does not always correlate with the severity of the disease and the degree of expression of toxicosis symptoms. It is also known that the concentration of viral antigens does not strictly correlate with the severity of intoxication. On the contrary, with an increase in the severity of the disease, and therefore, the increase in the degree of toxicosis, the concentration of HBsAg decreases and is lowest in malignant forms at the time of the onset of deep hepatic coma. At the same time, the frequency of detection and titers of specific antiviral antibodies directly depend on the severity of the disease.

Intoxication appears not at the moment of registration of viral antigens, but during the period of circulation in the blood of antiviral antibodies of class IgM to the cow antigen and the antigen of the E system. Moreover, in severe and especially malignant forms, a significant proportion of patients even have anti-HBs in the blood, which is usually never observed in mild and moderate forms of the disease.

The presented data allow us to conclude that the toxicosis syndrome in viral hepatitis, and hepatitis B in particular, does not arise as a result of the appearance of viral antigens in the blood, but is a consequence of the interaction of viral antigens with antiviral antibodies of the IgM class. The result of such interaction, as is known, is the formation of immune complexes and, possibly, active toxic substances.

Symptoms of intoxication arise at the moment of the appearance of immune complexes in free circulation, but subsequently such a correlation is not observed.

A partial explanation for this can be found in the study of the composition of immune complexes. In patients with severe forms, predominantly medium-sized complexes circulate in the blood, and in their composition, at the height of the toxic syndrome, antibodies of the class predominate, whereas during the period of decline in clinical manifestations and convalescence, the complexes become larger, and in their composition, antibodies of the IgG class begin to predominate.

The presented data concern the mechanisms of development of toxic syndrome in the initial period of the disease, but in toxicosis occurring at the height of clinical manifestations, they have only partial significance, and especially in the development of hepatic coma.

The method of blood cultures has shown that with hepatitis B, toxins constantly accumulate in the blood, released from the damaged, decaying liver tissue. The concentration of these toxins is proportional to the severity of the disease, they are of a protein nature.

During the recovery period, antibodies to this toxin appear in the blood; but in the event of hepatic coma, the concentration of the toxin in the blood increases sharply, and antibodies are not detected in the blood.

Pathomorphology of hepatitis B

Based on the nature of morphological changes, three forms of acute hepatitis B are distinguished:

- cyclic form,

- massive liver necrosis;

- cholestatic pericholangiolytic hepatitis.

In the cyclic form of hepatitis B, dystrophic, inflammatory and proliferative changes are more pronounced in the center of the lobules, while in hepatitis A they are localized along the periphery of the lobule, spreading to the center. These differences are explained by different routes of virus penetration into the liver parenchyma. The hepatitis A virus enters the liver through the portal vein and spreads to the center of the lobules, the hepatitis B virus penetrates through the hepatic artery and capillary branches that evenly supply all the lobules, right up to their center.

The degree of damage to the liver parenchyma in most cases corresponds to the severity of the clinical manifestations of the disease. In mild forms, focal necrosis of hepatocytes is usually observed, and in moderate and severe forms - zonal necrosis (with a tendency to merge and form bridge-like necrosis in severe forms of the disease).

The greatest morphological changes in the parenchyma are observed at the height of clinical manifestations, which usually coincides with the first decade of the disease. During the 2nd and especially the 3rd decade, regeneration processes intensify. By this period, necrobiotic changes almost completely disappear and cellular infiltration processes begin to predominate with slow subsequent restoration of the structure of the hepatocellular plates. However, complete restoration of the structure and function of the liver parenchyma occurs only 3-6 months after the onset of the disease and not in all patients.

The generalized nature of the infection in hepatitis B is confirmed by the detection of HBsAg not only in hepatocytes, but also in the kidneys, lungs, spleen, pancreas, bone marrow cells, etc.

Cholestatic (pericholangiolytic) hepatitis is a special form of the disease, in which the greatest morphological changes are found on the part of the intrahepatic bile ducts, with a picture of cholangiolitis and pericholangiolitis. In the cholestatic form, cholestasis occurs with dilation of the bile capillaries with stasis of bile in them, with proliferation of cholangiole and cellular infiltrates around them. Liver cells are affected insignificantly in this form of hepatitis. Clinically, the disease is characterized by a protracted course with prolonged jaundice. It has been shown that the cause of such a peculiar course of the disease is the predominant effect of the virus on the walls of the cholangiole with an insignificant effect on hepatocytes.