Medical expert of the article

New publications

Cryptococcal meningitis

Last reviewed: 12.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

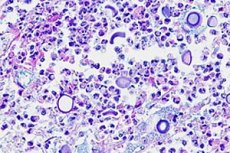

Inflammation of the meninges can be caused not only by bacteria, viruses, and protists, but also by fungal infections. Cryptococcal meningitis is caused by encapsulated yeast fungi Cryptococcus neoformans, which is an opportunistic pathogen of humans. [ 1 ] It was named Busse-Buschke disease due to its first description by Otto Busse and Abraham Buschke in 1894. [ 2 ]

According to ICD-10, the disease code is G02.1 (in the section on inflammatory diseases of the central nervous system), and also B45.1 in the section on mycoses (that is, fungal diseases).

Epidemiology

Eight out of ten cases of cryptococcal meningitis occur in people infected with HIV/AIDS.

According to data published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases in the spring of 2017, the fungus causes about 220,000 cases of cryptococcal meningitis each year among people with HIV or AIDS, and more than 180,000 die. Most cases of cryptococcal meningitis occur in sub-Saharan Africa.

According to WHO statistics, in 2017, 165.8 thousand cases of cryptococcal meningitis were registered in Africa, 43.2 thousand in Asian countries, 9.7 thousand in North and South America, and 4.4 thousand cases of the disease in European countries.

Causes cryptococcal meningitis

The causes of this type of meningitis are infection with the fungus Cryptococcus neoformans (class Tremellomycetes, genus Filobasidiella), which lives in the environment: in the soil (including dust), on rotting wood, in the droppings of birds (pigeons) and bats, etc. Infection occurs through the air - by inhaling aerosol basidiospores of the fungus, although in most people with sufficient immunity to the development of the disease, C. neoformans does not lead and remains a facultative intracellular opportunistic microorganism (which cannot infect other people). Read also - Cryptococci - causative agents of cryptococcosis [ 3 ]

As a rule, cryptococcal meningitis develops in HIV-infected individuals (at stage IVB) – as a secondary infection, as well as in people with a poorly functioning immune system in other diseases accompanied by long-term immunosuppression. [ 4 ]

Cryptococcal meningitis is considered a cerebral or extrapulmonary form of cryptococcosis, which develops after hematogenous dissemination of C. neoformans from the respiratory tract and lungs to the brain and spinal cord.[ 5 ]

Risk factors

The factors that increase the risk of developing cryptococcal meningitis include:

- neonatal period (newborn period) and prematurity of infants;

- weakening of the immune system in oncological diseases (including leukemia, multiple melanoma, lymphosarcoma), in patients with HIV infection and AIDS;

- diabetes;

- viral hepatitis and other immune complex diseases;

- sickle cell anemia;

- chemotherapy in the presence of an oncological diagnosis;

- exceeding the permissible level of ionizing radiation;

- long courses of antibiotic or steroid treatment;

- installation of intravascular catheters and shunts;

- bone marrow or internal organ transplant.

Pathogenesis

Cryptococci, protected from human immune cells by a polysaccharide capsule (which inhibits phagocytosis), secrete proteases, urease, phospholipase and nuclease – enzymes capable of destroying host cells. [ 6 ]

And the pathogenesis of cryptococcosis lies in the fact that these enzymes damage cells by lysing membranes, modifying molecules, disrupting the functions of cellular organelles and changing the cytoskeleton. [ 7 ]

Fungal serine proteases destroy the peptidic bonds of cellular proteins, cleave immunoglobulins and proteins of immune effector cells, and C. neoformans replication occurs within mononuclear phagocytes (macrophages), which facilitates their spread. [ 8 ]

In addition, by passing through endothelial cells and by being carried inside infected macrophages, cryptococci disrupt the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The fungus spreads through the bloodstream into the cerebrospinal fluid and then into the soft membranes of the brain, forming “colonies” of fungal cells in the brain tissue in the form of gelatinous pseudocysts. [ 9 ]

Symptoms cryptococcal meningitis

The first signs of cryptococcal meningitis are fever (temperature rises to +38.5-39°C) and severe headaches.

Clinical symptoms also include nausea and vomiting, seizures, stiffness of the neck, increased sensitivity of the eyes to light, and disturbances in consciousness and behavior. [ 10 ]

As experts note, the development of meningeal syndrome is slower than with bacterial infection of the meninges.

Complications and consequences

Complications and consequences of fungal meningitis caused by cryptococcus are:

- significant increase in intracranial pressure;

- isolated damage to the cranial nerves with paresis/paralysis of the facial nerve and atrophic changes in the optic nerve (leading to ophthalmological problems);

- the spread of the inflammatory process to the tissues of the subcortex and hemispheres of the brain - cryptococcal meningoencephalitis;

- development of brain abscess (cryptococcoma);

- effusion into the subdural space (under the dura mater of the brain);

- spinal cord injury;

- mental changes and decreased cognitive functions.

Diagnostics cryptococcal meningitis

In addition to the medical history and physical examination, diagnosis of C. neoformans infection in meningitis necessarily includes blood tests: general clinical and biochemical, blood serum analysis for antibodies to C. neoformans proteins, and blood culture.

A lumbar puncture is performed and an analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid for antigen and a bacterioscopic analysis (bacterial culture) of the cerebrospinal fluid is done. [ 11 ]

Instrumental diagnostics are carried out using chest X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes meningitis and meningoencephalitis of bacterial and viral etiology, brain damage by fungi Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, Blastomyces dermatidis or amoebas (including Naegleria fowleri).

Treatment cryptococcal meningitis

Etiological treatment is aimed at eradicating cryptococci, for which antifungal drugs are used.

The treatment regimen includes intravenous administration (drip, via a central venous catheter, or by peritoneal infusion) of the polyene antifungal antibiotic Amphotericin B (Amphocyl) in combination with the antifungal drug Flucytosine (5-fluorocytosine) or Fluconazole, which has a fungicidal and fungistatic effect. The dosage of these drugs is calculated depending on the patient's body weight.

Constant monitoring of the patient's condition is necessary, since Amphotericin B has a toxic effect on the kidneys, and the side effects of Flucytosine can include suppression of the hematopoietic function of the bone marrow, respiratory or cardiac arrest, the development of skin lesions in the form of epidermal necrolysis, etc.

According to the recommendations published in the 2010 IDSA (Infectious Diseases Society of America) update, treatment has not changed for ten years. First-line antifungal treatment is based on induction, consolidation, and maintenance of the following three types of patients: [ 12 ]

HIV-related diseases

- Induction therapy

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate (0.7-1.0 mg/kg/day) + flucytosine (100 mg/kg/day orally) for 2 weeks (Evidence A1)

- Liposomal amphotericin B (3-4 mg/kg/day) or lipid complex amphotericin B (5 mg/kg/day; monitor renal function) + flucytosine (100 mg/kg/day) for 2 weeks (Evidence B2)

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate (0.7 to 1.0 mg/kg/day) or liposomal amphotericin B (3 to 4 mg/kg/day) or amphotericin B lipid complex (5 mg/kg/day, for patients who cannot tolerate flucytosine) for 4 to 6 weeks (Evidence B2)

- Alternatives to induction therapy

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate + fluconazole (Evidence B1)

- Fluconazole + flucytosine (Evidence B2)

- Fluconazole (Evidence B2)

- Itraconazole (Evidence C2)

- Fluconazole (400 mg/day) for 8 weeks (Data A1)

- Fluconazole (200 mg/day) for 1 or more years (Evidence A1)

- Itraconazole (400 mg/day) for 1 or more years (Evidence C1)

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate (1 mg/kg/week) for 1 or more years (Evidence C1)

- Consolidation therapy

- Supportive therapy

- Alternatives to maintenance therapy

Transplant-related diseases

- Induction therapy

- Liposomal amphotericin B (3-4 mg/kg/day) or lipid complex amphotericin B (5 mg/kg/day) + flucytosine (100 mg/kg/day) for 2 weeks (Evidence B3)

- Alternatives to induction therapy

- Liposomal amphotericin B (6 mg/kg/day) or lipid complex amphotericin B (5 mg/kg/day) for 4-6 weeks (Evidence B3)

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate (0.7 mg/kg/day) for 4-6 weeks (Evidence B3)

- Fluconazole (400 to 800 mg/day) for 8 weeks (Evidence B3)

- Fluconazole (200 to 400 mg/day) for 6 months to 1 year (Evidence B3)

- Consolidation therapy

- Supportive therapy

Non-HIV/Transplant Related Disease

- Induction therapy

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate (0.7 to 1.0 mg/kg/day) + flucytosine (100 mg/kg/day) for 4 or more weeks (Evidence B2)

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate (0.7–1.0 mg/kg/day) for 6 weeks (Evidence B2)

- Liposomal amphotericin B (3-4 mg/kg/day) or lipid complex amphotericin B (5 mg/kg/day) in combination with flucytosine, 4 weeks (Evidence B3)

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate (0.7 mg/kg/day) + flucytosine (100 mg/kg/day) for 2 weeks (Evidence B2)

- Consolidation therapy

- Fluconazole (400 to 800 mg/day) for 8 weeks (Evidence B3)

- Fluconazole (200 mg/day) for 6-12 months (Evidence B3)

- Supportive therapy

The combination of amphotericin B and flucytosine has been shown to be the most effective in eliminating the infection and has shown a greater survival benefit than amphotericin alone. However, due to its cost, flucytosine is often unavailable in resource-limited settings where the disease burden is high. Combinations of amphotericin B and fluconazole have been studied and have shown superior results compared to amphotericin B alone.[ 13 ], [ 14 ], [ 15 ]

Without treatment, the clinical course progresses to confusion, seizures, decreased level of consciousness, and coma.

Headache refractory to analgesics may be treated with spinal decompression after adequate neuroimaging evaluation with CT or MRI. The safe maximum volume of CSF that can be drained with a single lumbar puncture is unclear, but up to 30 ml is often removed with pressure checking after each 10 ml removal.[ 16 ]

Prevention

Prevention of infection with the fungus Cryptococcus neoformans is necessary, first of all, in cases of a weak immune system. [ 17 ] It is recommended to avoid dusty places and working with soil, and HIV-infected people should receive ongoing antiretroviral therapy.

Forecast

Without treatment, the prognosis for any fungal meningitis is poor.

Initial prognosis depends on mortality predictors such as the following [ 18 ], [ 19 ]:

- The opening pressure of the cerebrospinal fluid is more than 25 cm H2O.

- Low white blood cell count in cerebrospinal fluid

- Sensory impairment

- Late diagnosis

- Elevated cerebrospinal fluid antigen titers

- Rate of infection clearance

- The amount of yeast in the CSF exceeds 10 mm3 ( common practice in Brazil) [ 20 ]

- Non-HIV related patients and prognostic factors in these patients, in addition to those already mentioned:

- Markers of a weak inflammatory response

- No headaches

- Primary hematological malignancy

- Chronic kidney or liver disease

Mortality varies from country to country depending on resource settings. It remains high in the United States and France, with 10-week mortality rates ranging from 15% to 26%, and even higher in HIV-uninfected patients due to late diagnosis and dysfunctional immune responses. On the other hand, in resource-poor countries, mortality increases from 30% to 70% at 10 weeks due to late presentation and lack of access to medications, blood pressure monitors, and optimal monitoring.