Medical expert of the article

New publications

Chronic meningitis

Last reviewed: 04.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Chronic meningitis is an inflammatory disease that, unlike the acute form, develops gradually over several weeks (sometimes more than a month). The symptoms of the disease are similar to those of acute meningitis: patients experience headaches, high fever, and sometimes neurological disorders. There are also characteristic pathological changes in the cerebrospinal fluid.

Epidemiology

One of the most pronounced outbreaks of meningitis occurred in 2009 in epidemically dangerous areas of West Africa – in the region of the “meningitis belt”, located south of the Sahara, between Senegal and Ethiopia. The outbreak affected countries such as Nigeria, Mali, Niger: almost 15 thousand cases were registered. Such outbreaks in these regions occur regularly, approximately every 6 years, and the causative agent of the disease is most often meningococcal infection.

Meningitis, including chronic meningitis, is characterized by a fairly high risk of death. Complications, immediate and remote, often develop.

In European countries, the disease is registered much less frequently - about 1 case per hundred thousand of the population. Children are more often ill (about 85% of cases), although in general people of any age can get sick. Meningitis is especially common in infants.

The pathology was first described by Hippocrates. The first officially registered outbreaks of meningitis occurred in the 19th century in Switzerland, North America, then in Africa and Russia. At that time, the mortality rate of the disease was over 90%. This figure decreased significantly only after the invention and introduction of a specific vaccine into practice. The discovery of antibiotics also contributed to the reduction in mortality. By the 20th century, epidemic outbreaks were registered less and less often. But even now, acute and chronic meningitis are considered fatal diseases that require immediate diagnosis and treatment.

Causes chronic meningitis

Chronic meningitis is usually caused by an infectious agent. Among the many different microorganisms, the most common "culprits" of the disease are:

- tuberculous mycobacteria; [ 1 ]

- the causative agent of Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi);

- fungal infection (including Cryptococcus neoformans, Cryptococcus gatti, Coccidioides immitis, Histoplasma capsulatum, blastomycetes).

Tuberculosis mycobacteria can cause rapidly progressing chronic meningitis. The disease develops during the primary infection of the patient, but in some people the pathogen remains inside the body in a "dormant" state, activating under favorable conditions and causing the development of meningitis. Activation can occur against the background of taking drugs that suppress the immune system (for example, immunosuppressants, chemotherapy drugs), or with other sharp decreases in immune protection.

Meningitis resulting from Lyme disease can be either acute or chronic. Most patients experience slow progression of the disease.

Fungal infection provokes the development of chronic inflammation of the meninges mainly in people with weak immunity, suffering from various immunodeficiency conditions. Sometimes fungal infection takes on a wave-like course: symptoms slowly increase, then disappear, and reappear.

Less common pathogens causing chronic meningitis include:

- pale treponema; [ 2 ]

- protozoa (for example, Toxoplasma gondii);

- viruses (in particular, enteroviruses).

Chronic meningitis is often diagnosed in HIV-infected patients, especially against the background of bacterial and fungal infections. [ 3 ] In addition, the disease may have a non-infectious etiology. Thus, chronic meningitis is sometimes found in patients with sarcoidosis, [ 4 ] systemic lupus erythematosus, [ 5 ] rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren's syndrome, Behcet's disease, lymphoma, leukemia. [ 6 ]

Fungal chronic meningitis can develop after injection of corticosteroids into the epidural space with violation of aseptic rules: such injections are used to relieve pain in patients with radiculitis. In this case, signs of the disease appear within several months after the injection. [ 7 ], [ 8 ]

Cerebral aspergillosis occurs in approximately 10-20% of patients with invasive disease and results from hematogenous spread of the organism or direct extension from rhinosinusitis.[ 9 ]

In some cases, people are diagnosed with chronic meningitis, but no infection is found during the tests. In such a situation, they talk about idiopathic chronic meningitis. It is noteworthy that this type of disease does not respond well to treatment, but often goes away on its own - self-healing occurs.

Risk factors

Almost any infectious pathology that causes inflammation can become provoking factors in the development of chronic meningitis. Weak immunity further increases the risk.

A person can become infected with an infectious disease from a sick person or a bacteria carrier (virus carrier) - an apparently healthy person who is contagious to others. The infection can be transmitted by airborne droplets or by contact in everyday conditions - for example, when using common cutlery, kissing, and also during cohabitation (camp, barracks, dormitory, etc.).

The risk of developing chronic meningitis increases significantly in children with immature immune defense (infancy), in people traveling to epidemically dangerous regions, in patients with immunodeficiency conditions. Smoking and alcohol abuse also have an adverse effect.

Pathogenesis

Infectious toxic processes play a leading role in the pathogenetic mechanism of chronic meningitis development. They are caused by large-scale bacteremia with pronounced bacterial decay and release of toxic products into the blood. Endotoxin exposure is caused by the release of toxins from the cell walls of the pathogen, which entails a violation of hemodynamics, microcirculation, and leads to intense metabolic disorders: oxygen deficiency and acidosis gradually increase, hypokalemia worsens. The coagulation and anticoagulation systems of the blood suffer. At the first stage of the pathological process, hypercoagulation is observed with an increase in the level of fibrinogen and other coagulation factors, and at the second stage, fibrin falls out in small vessels, blood clots are formed. With a further decrease in the level of fibrinogen in the blood, the likelihood of hemorrhages, bleeding into various organs and tissues of the body increases.

The pathogen's entry into the membranes of the brain initiates the development of symptoms and pathomorphological picture of chronic meningitis. At first, the inflammatory process affects the soft and arachnoid membranes, then it can spread to the brain substance. The type of inflammation is predominantly serous, and in the absence of treatment it turns into a purulent form. A characteristic sign of chronic meningitis is the gradually increasing damage to the spinal roots and cranial nerves.

Symptoms chronic meningitis

The main symptoms of chronic meningitis are persistent headache (possibly in combination with tension in the occipital muscles and hydrocephalus), radiculopathy with neuropathy of the cranial nerves, personality disorders, deterioration of memory and mental performance, as well as other disorders of cognitive functions. These manifestations can occur simultaneously or separately from each other.

Due to excitation of the nerve endings of the meninges, severe pain in the head is supplemented by pain in the neck and back. Hydrocephalus and increased intracranial pressure may develop, which in turn causes increased headache, vomiting, apathy, drowsiness, irritability. Edema of the optic nerves, deterioration of visual function, paresis of upward gaze are noted. Damage to the facial nerve is possible.

With the addition of vascular disorders, cognitive problems, behavioral disorders, and seizures appear. Acute cerebrovascular accidents and myelopathies may develop.

With the development of basal meningitis against the background of deterioration of vision, weakness of the facial muscles, deterioration of hearing and smell, sensory disturbances, and weakness of the chewing muscles are detected.

As the inflammatory process worsens, complications may develop in the form of edema and swelling of the brain, infectious toxic shock with the development of DIC syndrome.

First signs

Since chronic meningitis progresses slowly, the first signs of the pathology do not immediately make themselves known. The infectious process is manifested by a gradual increase in temperature, headache, general weakness, loss of appetite, as well as symptoms of an inflammatory reaction outside the central nervous system. In people suffering from immunodeficiency conditions, body temperature indicators may be within normal limits.

Chronic meningitis should be ruled out first if the patient has persistent, unremitting headache, hydrocephalus, progressive cognitive impairment, radicular syndrome, cranial neuropathy. If these signs are present, a spinal puncture should be performed, or at least an MRI or CT scan should be performed.

The most likely initial symptoms of chronic meningitis are:

- increase in temperature (stable readings within 38-39°C);

- headache;

- psychomotor disorders;

- deterioration of gait;

- double vision;

- convulsive muscle twitching;

- visual, auditory, olfactory problems;

- meningeal signs of varying intensity;

- disturbances of the facial muscles, tendon and periosteal reflexes, the appearance of spastic thymes and paraparesis, rarely - paralysis with hyper or hypoesthesia, coordination disorders;

- cortical disturbances in the form of mental disorders, partial or complete amnesia, auditory or visual hallucinations, euphoric or depressive states.

Symptoms of chronic meningitis can last for months or even years. In some cases, patients may notice a visible improvement, after which a relapse occurs again.

Complications and consequences

The consequences of chronic meningitis are almost impossible to predict. In most cases, they develop in the late period and can be expressed in the following disorders:

- neurological complications: epilepsy, dementia, focal neurological defects;

- systemic complications: endocarditis, thrombosis and thromboembolism, arthritis;

- neuralgia, cranial nerve palsy, contralateral hemiparesis, visual impairment;

- hearing loss, migraines.

In many cases, the likelihood of complications depends on the underlying cause of chronic meningitis and the state of a person's immunity. Meningitis caused by a parasitic or fungal infection is more difficult to cure and tends to recur (especially in HIV-infected patients). Chronic meningitis that develops against the background of leukemia, lymphoma, or cancerous neoplasms has a particularly unfavorable prognosis.

Diagnostics chronic meningitis

If chronic meningitis is suspected, a general blood test and a spinal puncture to examine the cerebrospinal fluid (if there are no contraindications) are required. After the spinal puncture, blood is examined to assess the glucose level.

Additional tests:

- biochemical blood test;

- determination of the leukocyte formula;

- Blood culture test with PCR.

In the absence of contraindications, a spinal puncture is performed as soon as possible. A sample of cerebrospinal fluid is sent to the laboratory: this procedure is fundamental for the diagnosis of chronic meningitis. The following are determined as standard:

- number of cells, protein, glucose;

- Gram staining, culture, PCR.

The following signs may indicate the presence of meningitis:

- high blood pressure;

- turbidity of the liquor;

- increased number of leukocytes (mainly polymorphonuclear neutrophils);

- elevated protein levels;

- low ratio of glucose levels in cerebrospinal fluid and blood.

Other biological materials, such as urine or sputum samples, may be collected for bacterial culture.

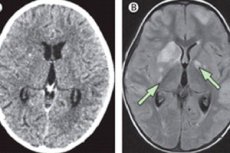

Instrumental diagnostics may include magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography, biopsy of altered skin (with cryptococcosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Lyme disease, trypanosomiasis) or enlarged lymph nodes (with lymphoma, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, secondary syphilis or HIV infection).

A thorough examination by an ophthalmologist is carried out. It is possible to detect uveitis, dry keratoconjunctivitis, iridocyclitis, and deterioration of visual function due to hydrocephalus.

A general examination can reveal aphthous stomatitis, hypopyon or ulcerative lesions – in particular, those characteristic of Behcet's disease.

Enlargement of the liver and spleen may indicate the presence of lymphoma, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, brucellosis. In addition, chronic meningitis can be suspected if there are additional sources of infection in the form of purulent otitis, sinusitis, chronic pulmonary pathologies, or provoking factors in the form of intrapulmonary blood shunting.

It is very important to collect epidemiological information correctly and completely. The most important anamnestic data are the following:

- the presence of tuberculosis or contact with a tuberculosis patient;

- travel to epidemiologically unfavorable regions;

- the presence of immunodeficiency states or a sharp weakening of the immune system. [ 10 ]

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnostics are carried out with various types of meningitis (viral, tuberculous, borreliosis, fungal, caused by protozoa), as well as:

- with aseptic meningitis associated with systemic pathologies, neoplastic processes, chemotherapy;

- with viral encephalitis;

- with brain abscess, subarachnoid hemorrhage;

- with neoblastoses of the central nervous system.

The diagnosis of chronic meningitis is based on the results of a study of cerebrospinal fluid, as well as information obtained during etiological diagnostics (culture, polymerase chain reaction). [ 11 ]

Treatment chronic meningitis

Depending on the origin of chronic meningitis, the doctor prescribes appropriate treatment:

- if tuberculosis, syphilis, Lyme disease, or another bacterial process is diagnosed, antibiotic therapy is prescribed according to the sensitivity of specific microorganisms;

- if there is a fungal infection, antifungal agents are prescribed, mainly Amphotericin B, Flucytosine, Fluconazole, Voriconazole (orally or by injection);

- if a non-infectious nature of chronic meningitis is diagnosed – in particular, sarcoidosis, Behcet's syndrome – corticosteroids or immunosuppressants are prescribed for a long time;

- If cancer metastases are detected in the membranes of the brain, radiation therapy of the head area and chemotherapy are combined.

For chronic meningitis caused by cryptococcosis, Amphotericin B is prescribed together with Flucytosine or Fluconazole.

In addition, symptomatic treatment is used: analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics and detoxifying drugs are used according to indications. [ 12 ]

Prevention

Preventive measures to prevent the development of chronic meningitis include the following recommendations:

- compliance with personal hygiene rules;

- avoiding close contact with sick people;

- inclusion in the diet of foods rich in vitamins and microelements;

- during periods of seasonal disease outbreaks, avoiding areas with large crowds of people (especially indoor areas);

- drinking only boiled or bottled water;

- consumption of thermally processed meat, dairy and fish products;

- avoiding swimming in stagnant waters;

- wet cleaning of residential premises at least 2-3 times a week;

- general hardening of the body;

- avoiding stress and hypothermia;

- maintaining an active lifestyle, maintaining physical activity;

- timely treatment of various diseases, especially those of infectious origin;

- quitting smoking, drinking alcohol and taking drugs;

- refusal of self-medication.

In many cases, chronic meningitis can be prevented by timely diagnosis and treatment of systemic diseases.