Medical expert of the article

New publications

Laryngoscopy

Last reviewed: 06.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Laryngoscopy is the main type of examination of the larynx. The difficulty of this method is that the longitudinal axis of the larynx is located at a right angle to the axis of the oral cavity, which is why the larynx cannot be examined in the usual way.

Examination of the larynx can be performed either with the help of a laryngeal mirror (indirect laryngoscopy), when using which the laryngoscopic image is mirrored, or with the help of special directoscopes designed for direct laryngoscopy.

Indirect laryngoscopy

In 1854, the Spanish singer Garcia (son) Manuel Patricio Rodriguez (1805-1906) invented a laryngoscope for indirect laryngoscopy. For this invention, he was awarded the degree of Doctor of Medicine in 1855. It should be noted, however, that the method of indirect laryngoscopy was known from earlier publications, beginning in 1743 (the glotoscope of the obstetrician Levert). Then Dozzini (Frankfurt, 1807), Sem (Geneva, 1827), and Babynston (London, 1829) reported on similar devices that operated on the periscope principle and allowed for a mirror image examination of the interior of the larynx. In 1836 and 1838, the Lyon surgeon Baums demonstrated a laryngeal mirror that exactly corresponded to the modern one. Then in 1840 Liston used a mirror similar to a dentist's mirror, which he used to examine the larynx in a disease that caused its swelling. The wide introduction of the Garcia laryngoscope into medical practice is due to the neurologist of the Vienna hospital L. Turck (1856). In 1858, the professor of physiology from Pest (Hungary) Schrotter first used artificial lighting and a round concave mirror with a hole in the middle (Schroetter's reflector) for indirect laryngoscopy with a rigid vertical Kramer head adapted to it. Previously, sunlight reflected by a mirror was used to illuminate the larynx and pharynx.

Modern techniques of indirect laryngoscopy are no different from those used 150 years ago.

Flat laryngeal mirrors of various diameters are used, attached to a narrow rod inserted into a special handle with a screw lock. To avoid fogging of the mirror, it is usually heated on an alcohol lamp with the mirror surface to the flame or in hot water. Before inserting the mirror into the oral cavity, its temperature is checked by touching the back metal surface to the skin of the back of your hand. Indirect laryngoscopy is usually performed in a sitting position with the patient's body slightly tilted forward and head slightly tilted back. If removable dentures are present, they are removed. The technique of indirect laryngoscopy requires certain skills and appropriate training. The essence of the technique is as follows. The doctor takes the handle with the mirror fixed in it with his right hand, like a writing pen, so that the mirror surface is directed at an angle downwards. The patient opens his mouth wide and sticks out his tongue as much as possible. The doctor grasps the tongue wrapped in a gauze napkin with the first and third fingers of the left hand and holds it in a protruding position, at the same time, with the second finger of the same hand, lifts the upper lip for a better view of the pharyngeal region, directs a beam of light into the oral cavity and inserts a heated mirror into it. The back surface of the mirror is pressed against the soft palate, moving it back and up. To avoid reflection of the uvula of the soft palate in the mirror, which interferes with viewing the larynx, it must be completely covered with a mirror. When inserting the mirror into the oral cavity, do not touch the root of the tongue and the back wall of the pharynx, so as not to cause a pharyngeal reflex. The stem and handle of the mirror rest on the left corner of the mouth, and its surface should be oriented so that it forms an angle of 45° with the axis of the oral cavity. The light flux directed at the mirror and reflected from it into the larynx illuminates it and the corresponding anatomical structures. To examine all structures of the larynx, the angle of the mirror is changed by manipulating the handle so as to consistently examine the interarytenoid space, arytenoids, vestibular folds, vocal folds, pyriform sinuses, etc. Sometimes it is possible to examine the subglottic space and the posterior surface of two or three tracheal rings. The larynx is examined during calm and forced breathing of the subject, then during phonation of the sounds "i" and "e". When these sounds are pronounced, the muscles of the soft palate contract, and protruding the tongue helps to lift the epiglottis and open the supraglottic space for examination. At the same time, phonatory closure of the vocal folds occurs. Examination of the larynx should not last more than 5-10 seconds, a repeat examination is carried out after a short pause.

Sometimes examination of the larynx by indirect laryngoscopy causes significant difficulties. The obstructing factors include an infantile, slightly mobile epiglottis blocking the entrance to the larynx; a pronounced (uncontrollable) gag reflex, most often observed in smokers, alcoholics, neuropaths; a thick, "unruly" tongue and a short frenulum; a comatose or soporous state of the examined person and a number of other reasons. An obstacle to examining the larynx is contracture of the temporomandibular joint, which occurs with a peritonsillar abscess or its arthrosis arthritis, as well as with mumps, phlegmon of the oral cavity, a fracture of the lower jaw or trismus caused by some diseases of the central nervous system. The most common obstacle to indirect laryngoscopy is a pronounced pharyngeal reflex. There are some techniques for suppressing it. For example, the subject is asked to mentally count two-digit numbers backwards as a distraction, or to clasp the hands with bent fingers and pull them with all his might, or the subject is asked to hold his tongue. This technique is also necessary when the doctor must have both hands free to perform certain manipulations inside the larynx, such as removing a fibroma on the vocal fold.

In case of an uncontrollable gag reflex, application anesthesia of the root of the tongue, soft palate and back wall of the pharynx is used. Preference should be given to lubrication rather than aerosol spraying of the anesthetic, since the latter causes anesthesia that spreads to the mucous membrane of the oral cavity and larynx, which can cause spasm of the latter. Indirect laryngoscopy is almost impossible in young children, therefore, if mandatory examination of the larynx is necessary (for example, in case of its papillomatosis), direct laryngoscopy under anesthesia is used.

Picture of the larynx during indirect laryngoscopy

The picture of the larynx during indirect laryngoscopy is very characteristic, and since it is the result of a mirror image of the true picture, and the mirror is located at an angle of 45° to the horizontal plane (the periscope principle), the image is located in the vertical plane. With this arrangement of the displayed endoscopic picture, the anterior sections of the larynx are visible in the upper part of the mirror, often covered at the commissure by the epiglottis; the posterior sections, including the arytenoids and interarytenoid space, are displayed in the lower part of the mirror.

Since indirect laryngoscopy allows examination of the larynx with only the left eye, i.e. monocularly (which can be easily verified by closing it), all elements of the larynx are visible in one plane, although the vocal folds are located 3-4 cm below the edge of the epiglottis. The lateral walls of the larynx are visualized as sharply shortened and as if in profile. From above, i.e. actually from the front, part of the root of the tongue with the lingual tonsil is visible, then the pale pink epiglottis, the free edge of which rises during phonation of the sound "i", freeing the cavity of the larynx for viewing. Directly under the epiglottis in the center of its edge, a small tubercle can sometimes be seen - tubеrculum cpiglotticum, formed by the leg of the epiglottis. Below and behind the epiglottis, diverging from the angle of the thyroid cartilage and commissure to the arytenoid cartilages, are the vocal folds of a whitish-pearlescent color, easily identified by their characteristic quivering movements, sensitively reacting even to a slight attempt at phonation. During quiet breathing, the lumen of the larynx has the form of an isosceles triangle, the lateral sides of which are represented by the vocal folds, the apex seems to rest against the epiglottis and is often covered by it. The epiglottis is an obstacle to examining the anterior wall of the larynx. To overcome this obstacle, the Turk position is used, in which the person being examined throws back his head, and the doctor performs indirect laryngoscopy standing, as if from top to bottom. For a better view of the posterior sections of the larynx, the Killian position is used, in which the doctor examines the larynx from below (standing on one knee in front of the patient), and the patient tilts his head down.

Normally, the edges of the vocal folds are even and smooth; when inhaling, they diverge slightly; during a deep inhalation, the vocal folds diverge to the maximum distance and the upper rings of the trachea become visible, and sometimes even the tracheal carina. In some cases, the vocal folds have a dull reddish hue with a fine vascular network. In thin individuals, of asthenic build with a pronounced Adam's apple, all internal elements of the larynx stand out more clearly, the boundaries between fibrous and cartilaginous tissues are well differentiated.

In the superolateral regions of the laryngeal cavity, the vestibular folds, pink and more massive, are visible above the vocal folds. They are separated from the vocal folds by spaces that are more visible in thin individuals. These spaces are the entrances to the ventricles of the larynx. The interarytenoid space, which is like the base of the triangular slit of the larynx, is limited by the arytenoid cartilages, which are visible as two club-shaped thickenings covered with a pink mucous membrane. During phonation, they can be seen rotating towards each other with their anterior parts and bringing the vocal folds attached to them closer together. The mucous membrane covering the back wall of the larynx becomes smooth when the arytenoid cartilages diverge during inspiration; during phonation, when the arytenoid cartilages come closer together, it gathers into small folds. In some individuals, the arytenoid cartilages are so closely adjacent that they overlap. From the arytenoid cartilages, the aryepiglottic folds extend upward and forward, reaching the lateral margins of the epiglottis and together with it forming the upper boundary of the entrance to the larynx. Sometimes, with subatrophic mucous membrane, small elevations above the arytenoid cartilages can be seen in the thickness of the aryepiglottic folds; these are the corniculate cartilages; lateral to them are the wedge-shaped cartilages. To examine the posterior wall of the larynx, the Killian position is used, in which the person being examined tilts his head toward his chest, and the physician examines the larynx from the bottom up, either kneeling in front of the patient or standing.

Indirect laryngoscopy also reveals some other anatomical structures. Thus, above the epiglottis, actually in front of it, are visible the epiglottic fossae formed by the lateral glosso-epiglottic fold and separated by the medial glosso-epiglottic fold. The lateral parts of the epiglottis are connected to the walls of the pharynx by means of the pharyngeal-epiglottic folds, which cover the entrance to the piriform sinuses of the laryngeal part of the pharynx. During the expansion of the glottis, the volume of these sinuses decreases, and during the narrowing of the glottis, their volume increases. This phenomenon occurs due to the contraction of the interarytenoid and aryepiglottic muscles. It is of great diagnostic importance, since its absence, especially on one side, is the earliest sign of tumor infiltration of these muscles or the onset of neurogenic damage to them.

The color of the mucous membrane of the larynx should be assessed in accordance with the anamnesis of the disease and other clinical signs, since normally it is not constant and often depends on smoking, alcohol consumption, and exposure to occupational hazards. In hypotrophic (asthenic) individuals with asthenic physique, the color of the mucous membrane of the larynx is usually pale pink; in normosthenics - pink; in obese, plethoric (hypersthenic) individuals or smokers, the color of the mucous membrane of the larynx can be from red to cyanotic without any pronounced signs of disease of this organ.

Direct laryngoscopy

Direct laryngoscopy allows examining the internal structure in a direct image and performing various manipulations on its structures in a fairly wide range (removal of polyps, fibromas, papillomas by conventional, cryo- or laser surgical methods), as well as performing emergency or planned intubation. The method was introduced into practice by M. Kirshtein in 1895 and subsequently improved many times. It is based on the use of a rigid directoscope, the introduction of which into the laryngopharynx through the oral cavity becomes possible due to the elasticity and pliability of the surrounding tissues.

Indications for direct laryngoscopy

Indications for direct laryngoscopy are numerous and their number is constantly growing. This method is widely used in pediatric otolaryngology, since indirect laryngoscopy in children is almost impossible. For young children, a one-piece laryngoscope with a non-removable handle and a fixed spatula is used. For adolescents and adults, laryngoscopes with a removable handle and a retractable spatula plate are used. Direct laryngoscopy is used when it is necessary to examine parts of the larynx that are difficult to view with indirect laryngoscopy - its ventricles, commissure, anterior wall of the larynx between the commissure and epiglottis, subglottic space. Direct laryngoscopy allows for various endolaryngeal diagnostic manipulations, as well as for inserting an intubation tube into the larynx and trachea during anesthesia or intubation in case of emergency mechanical ventilation.

Contraindications for the procedure

Direct laryngoscopy is contraindicated in cases of severe stenotic breathing, severe changes in the cardiovascular system (decompensated heart defects, severe hypertension and angina), epilepsy with a low seizure threshold, lesions of the cervical vertebrae that do not allow the head to be thrown back, and aortic aneurysm. Temporary or relative contraindications include acute inflammatory diseases of the mucous membrane of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, bleeding from the pharynx and larynx.

Technique of direct laryngoscopy

Of great importance for the effective performance of direct laryngoscopy is the individual selection of the appropriate model of laryngoscope (Jackson, Undritz, Brunings Mezrin, Zimont, etc.), which is determined by many criteria - the purpose of interventions (diagnostic or surgical), the position of the patient in which laryngoscopy is supposed to be performed, his age, anatomical features of the maxillofacial and cervical regions and the nature of the disease. The study is carried out on an empty stomach, except for emergency cases. In young children, direct laryngoscopy is performed without anesthesia, in younger children - under anesthesia, older children - either under anesthesia or under local anesthesia with appropriate premedication, as in adults. For local anesthesia, various topical anesthetics can be used in combination with sedatives and anticonvulsants. To reduce general sensitivity, muscle tension and salivation, the patient is given one tablet of phenobarbital (0.1 g) and one tablet of sibazon (0.005 g) 1 hour before the procedure. 30-40 minutes before, 0.5-1.0 ml of a 1% solution of promedol and 0.5-1 ml of a 0.1% solution of atropine sulfate are administered subcutaneously. 10-15 minutes before the procedure, application anesthesia is administered (2 ml of a 2% solution of dicaine or 1 ml of a 10% solution of cocaine). 30 minutes before the specified premedication, in order to avoid anaphylactic shock, it is recommended to administer 1-5 ml of a 1% solution of dimedrome or 1-2 ml of a 2.5% solution of diprazine (pipolfen) intramuscularly.

The position of the patient may vary and is determined mainly by the patient's condition. It can be performed in a sitting position, lying on the back, less often in a position on the side or on the stomach. The most comfortable position for the patient and the doctor is the lying position. It is less tiring for the patient, prevents saliva from flowing into the trachea and bronchi, and in the presence of a foreign body, prevents its penetration into the deeper parts of the lower respiratory tract. Direct laryngoscopy is performed in compliance with the rules of asepsis.

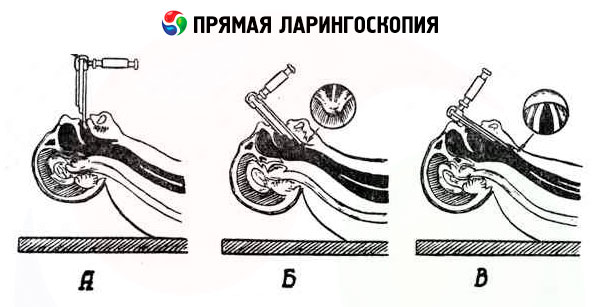

The procedure consists of three stages:

- advancement of the spatula towards the epiglottis;

- passing it through the edge of the epiglottis in the direction of the entrance to the larynx;

- its advancement along the posterior surface of the epiglottis to the vocal folds.

The first stage can be carried out in three variants:

- with the tongue sticking out, which is held in place with a gauze napkin either by the doctor's assistant or by the examiner himself;

- with the tongue in the normal position in the oral cavity;

- when inserting a spatula from the corner of the mouth.

In all variants of direct laryngoscopy, the upper lip is moved upward. The first stage is completed by pressing the root of the tongue downwards and moving the spatula to the edge of the epiglottis.

At the second stage, the end of the spatula is slightly raised, placed behind the edge of the epiglottis and advanced by 1 cm; after this, the end of the spatula is lowered down, covering the epiglottis. In this case, the spatula presses on the upper incisors (this pressure should not be excessive). The correct direction of the spatula advancement is confirmed by the appearance of whitish vocal folds in the friction field behind the arytenoid cartilages, extending from them at an angle.

When approaching the third stage, the patient's head is tilted back even more. The tongue, if it was held outside, is released. The examiner increases the pressure of the spatula on the root of the tongue and the epiglottis (see the third position - the direction of the arrows) and, adhering to the midline, positions the spatula vertically (with the patient in a sitting position) accordingly along the longitudinal axis of the larynx (with the patient in a lying position). In both cases, the end of the spatula is directed along the middle part of the respiratory slit. In this case, the posterior wall of the larynx comes into the field of view first, then the vestibular and vocal folds, and the ventricles of the larynx. For a better view of the anterior sections of the larynx, the root of the tongue should be pressed down slightly.

Special types of direct laryngoscopy include the so-called suspension laryngoscopy proposed by Killian, an example of which is the Seifert method. Currently, the Seifert principle is used when pressure on the root of the tongue (the main condition for introducing the spatula into the larynx) is provided by counterpressure of a lever resting on a special metal stand or on the chest of the person being examined.

The main advantage of the Seifert method is that it frees both hands of the doctor, which is especially important during long and complex endolaryngeal surgical interventions.

Modern foreign laryngoscopes for suspension and support laryngoscopy are complex systems, which include spatulas of various sizes and sets of various surgical instruments, specially adapted for endolaryngeal intervention. These systems are equipped with technical means for infectious artificial ventilation, injection anesthesia and special video equipment, allowing to perform surgical interventions using an operating microscope and a television screen.

[

[