New publications

Study identifies bacteria linked to preterm labor

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

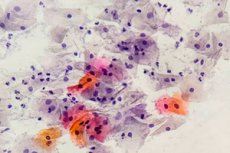

Researchers at North Carolina State University have found that multiple species of Gardnerella, bacteria sometimes associated with bacterial vaginosis (BV) and preterm labor, can coexist in the same vaginal microbiome. The findings, published in the journal mSystems, add to a growing understanding of the impact of Gardnerella on human health.

Gardnerella is a group of anaerobic bacteria that are common in the vaginal microbiome. Elevated levels of these bacteria are a hallmark of BV and are associated with an increased risk of preterm birth, but they are also found in women with no evidence of the disease.

"We were trying to understand the diversity within Gardnerella," says Ben Callahan, an associate professor of population health and pathobiology at North Carolina State University and a co-author of the paper.

"Scientists have only recently begun to study individual species of Gardnerella, so we don't yet know whether different species might have different health effects. Our main goal was to study the ecology of Gardnerella."

A unique challenge of vaginal microbiome sequencing is that any samples are primarily composed of host DNA, making microbial data extraction more expensive and labor-intensive. The research team’s first task was to develop a methodology that would allow identification of different Gardnerella species from microbiome data.

"The tools available to study the vaginal microbiome treat all Gardnerella as a single species," said Hannah Berman, a postdoctoral fellow at North Carolina State University and lead author of the paper. "To do this work, we had to build our own database of Gardnerella genomes and develop a method to identify different species of Gardnerella. Hopefully, this will also allow more researchers to study the diversity of Gardnerella."

The research team examined sequencing data from three cohorts: two random populations of pregnant women and one population with a history of preterm birth. They analyzed the metagenomic sequences of Gardnerella from the samples to see if there was an association between specific Gardnerella species and preterm birth.

Although they didn't find the "smoking gun," they did make two surprising discoveries.

First, they identified a potential 14th species of Gardnerella among the samples—prior to this work, only 13 species had been identified.

They also found that in most samples that contained Gardnerella, multiple Gardnerella species coexisted in the same microbiome: between two and all 14 known Gardnerella species were found in individual samples.

"Usually, if a species of bacteria colonizes an environment, we expect it to exclude close relatives that occupy the same ecological niche and consume the same resources," Callahan says. "I often say that with bacteria, anything is possible, but this is still unusual. We also saw that when the overall microbial load is higher, Gardnerella makes up a larger portion of that load.

"The evidence continues to accumulate that Gardnerella is linked to preterm birth, but the details of this relationship are complex. In this work, we did not find one harmful species of Gardnerella - perhaps they are all harmful. This is far from the end of the story."

The researchers hope to further study issues of species coexistence and microbiome composition.

"The vaginal microbiome is underappreciated," Callahan says. "For example, it's often dominated by one species of Lactobacillus, which creates an environment that excludes other bacteria. When that's gone, Gardnerella is there. So how do these bacteria interact?

"Answers to these questions could lead to more effective treatments for BV and ways to predict and prevent preterm birth. This work is an important step in that process."