New publications

Dreaming is associated with improved memory consolidation and emotion regulation

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

A night spent dreaming may help you forget the mundane and better process the extreme, according to a new study from the University of California, Irvine. The new work by researchers at the UC Irvine Sleep and Cognition Lab examined how dream memories and mood influence memory consolidation and emotion regulation the next day.

The findings, published recently in the journal Scientific Reports, suggest a trade-off in which emotionally charged memories are prioritized but their severity is reduced.

"We found that people who report dreaming show greater emotional memory processing, suggesting that dreams help us process our emotional experiences," said lead study author Sarah Mednick, a UC Irvine professor of cognitive science and director of the lab.

"This is important because we know that dreams can reflect our waking experiences, but this is the first evidence that they play an active role in transforming our responses to waking experiences, prioritizing negative memories over neutral ones and reducing our emotional reactivity the next day."

Lead author Jing Zhang, who received her PhD in cognitive science from UC Irvine in 2023 and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard Medical School, added: "Our work provides the first empirical evidence for the active involvement of dreams in sleep-dependent emotional memory processing, suggesting that dreaming after an emotional experience may help us feel better the next morning."

The study included 125 women — 75 via Zoom and 50 in the Sleep and Cognition Lab — who were in their 30s and part of a larger research project examining the effects of the menstrual cycle on sleep.

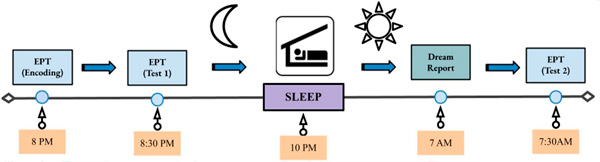

Each session began at 7:30 p.m. for subjects with an emotional picture task in which they viewed a series of pictures depicting negative and neutral situations (e.g., a car accident or a field of grass), rating each on a nine-point scale for the intensity of the feelings they evoked.

Participants then immediately completed the same test with new images and only a subset of previously viewed images. In addition to rating their emotional responses, the women had to indicate whether each image was old or new, which helped the researchers develop a baseline for both memory and emotional response.

The subjects then went to sleep either at home or in one of the sleep lab's private bedrooms. All wore a ring that tracked their sleep-wake patterns. When they woke up the next day, they rated whether they had dreamed the night before and, if so, recorded dream details and their overall mood in a sleep diary, using a seven-point scale from extremely negative to extremely positive.

Study protocol. At 8 p.m., participants memorized images from an EPT (emotional picture task) task and then underwent immediate testing. Participants then slept either at home or in the lab, depending on whether they were tested remotely or in person. Upon awakening, participants reported the presence and content of their dreams and underwent delayed EPT testing. Source: Scientific Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-58170-z

Two hours after waking up, the women repeated the second emotional picture task to measure their memory of and reactions to the images.

"Unlike typical sleep diary studies that collect data over several weeks to see whether daytime experiences appear in dreams, we used a single-night study that focused on emotionally charged material and asked whether dream recall was associated with changes in memory and emotional response," Zhang said.

Participants who reported dreams remembered negative images better and were less reactive to them than neutral images, which was not the case for those who did not remember dreams. In addition, the more positive the dream, the more positively the participant rated negative images the following day.

"This research gives us new insight into the active role of dreams in how we naturally process our everyday experiences and may lead to interventions that increase dreaming to help people cope with difficult life situations," Mednick said.