Why Sleep Calms Stress: Neuroscience Explained

Last reviewed: 14.06.2024

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

The study, published in Nature Reviews Neuroscience by an international team including Dr. Rick Wasing of the Woolcock Institute, reviewed more than two decades of sleep disorder research and found that good Night sleep is an ideal remedy for emotional stress.

“Some might say this is a known fact, but our work explains why this is so,” says Dr. Wasing, who has devoted the last two years to this project. "We looked at research from the fields of neuroscience, neurochemistry and clinical psychology to gain real insight into the mechanisms underlying how sleep helps us cope with emotional memories."

A team of researchers, summarizing more than 20 years of scientific knowledge, has concluded that the regulation of certain neurochemicals (for example, serotonin and norepinephrine) during sleep is key to the processing of emotional memories and long-term mental health.

Chemistry and neural circuits

Serotonin is involved in many, if not all, aspects of emotional learning, helping us evaluate and understand the world around us. Norepinephrine is responsible for the fight-or-flight response and helps assess and respond to danger. Both neurotransmitters turn off during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, creating "a really great opportunity for the brain to engage in processes that aren't possible when we're awake," explains Dr. Wasing.

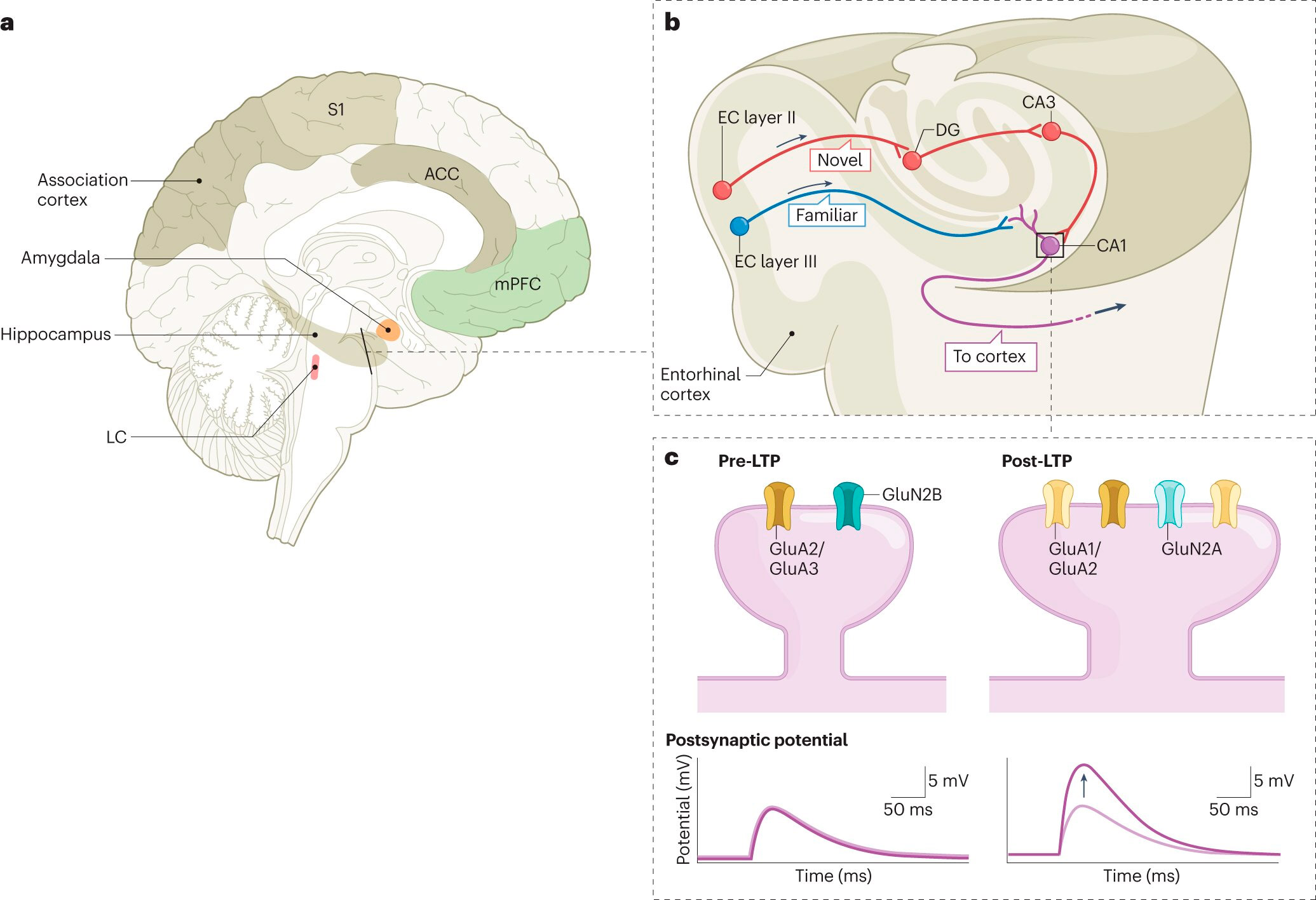

There are two main ways that emotional memories are processed during sleep, and they involve the hippocampus and the amygdala.

Our brain stores what we learn every day, with the hippocampus aggregating and cataloging this new information into “recency” memory. At the same time, if the new experience is emotional, the amygdala is very active and connected to the autonomic nervous system, which causes an increased heart rate and other physical reactions.

During REM sleep, the brain reactivates these new memories, replaying them as if all over again. But when the noradrenergic and serotonergic systems are turned off, these memories can be moved into “familiar” storage without the physical fight-or-flight response. This is not possible when we are awake or when people with sleep disorders do not receive consistent periods of REM sleep.

New opportunities for the treatment of sleep disorders

Much of what we know about how information is processed in the brain comes from the relatively new field of optogenetics, which allows very specific types of cells in a neural network to be activated or inhibited. This allowed the researchers to see which cell types and brain regions are involved in encoding emotional memories.

System, chain and molecular levels of the memory trace. Source: Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41583-024-00799-w

“At the neuronal, receptor, and neuronal circuit levels, our research has shown that shutting down amygdala reactivity and suppressing the autonomic nervous system during REM sleep is critical,” says Dr. Wasing.

Creating "good sleepers"

"We know that with insomnia or other sleep disorders, when people wake up frequently, their risk of developing mental health problems increases. Our hypothesis is that these awakenings lead to to the fact that the noradrenergic system does not turn off for a long time (and perhaps even shows increased activity), and therefore these people cannot regulate emotional memories."

"The solution is to try to get a good night's sleep, but how to do this? We know that two out of three people with insomnia benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI), but this is largely based on subjective estimates. A patient with insomnia after CBTI does not necessarily become a good sleeper, they may still have sleep disturbances, but CBTI helps them cope better with them."

"We have to critically look at the mechanisms that regulate sleep. It's very difficult to target one system because sleep is so dynamic—the noradrenergic system is turned off during REM sleep, but it must be active during non-REM sleep, so you can't just turn it off for the entire sleep."

"We need really creative ideas about how to develop an intervention or drug that can target these dynamic processes that occur during sleep and allow these systems to normalize. We need to strive for objective improvements in sleep and make people with insomnia good sleepers again."