New publications

Why sleep calms stress: a neurobiology explanation

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

A study published in the journal Nature Reviews Neuroscience by an international team including Dr Rick Wasing from the Woolcock Institute reviewed more than two decades of research into sleep disorders and found that a good night's sleep is the perfect antidote to emotional stress.

"Some might say this is a well-known fact, but our work explains why," says Dr. Wasing, who has spent the past two years on the project. "We looked at research in neuroscience, neurochemistry and clinical psychology to get a real understanding of the mechanisms behind how sleep helps us cope with emotional memories."

A team of researchers pooled more than 20 years of scientific knowledge to find that the regulation of certain neurochemicals (such as serotonin and norepinephrine ) during sleep is key to the processing of emotional memories and long-term mental health.

Chemistry and neural circuits

Serotonin is involved in many, if not all, aspects of emotional learning, helping us evaluate and understand the world around us. Norepinephrine is responsible for the fight-or-flight response and helps us evaluate and respond to danger. Both neurotransmitters are turned off during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, creating “a really wonderful opportunity for the brain to engage in processes that aren’t possible when we’re awake,” explains Dr. Wasing.

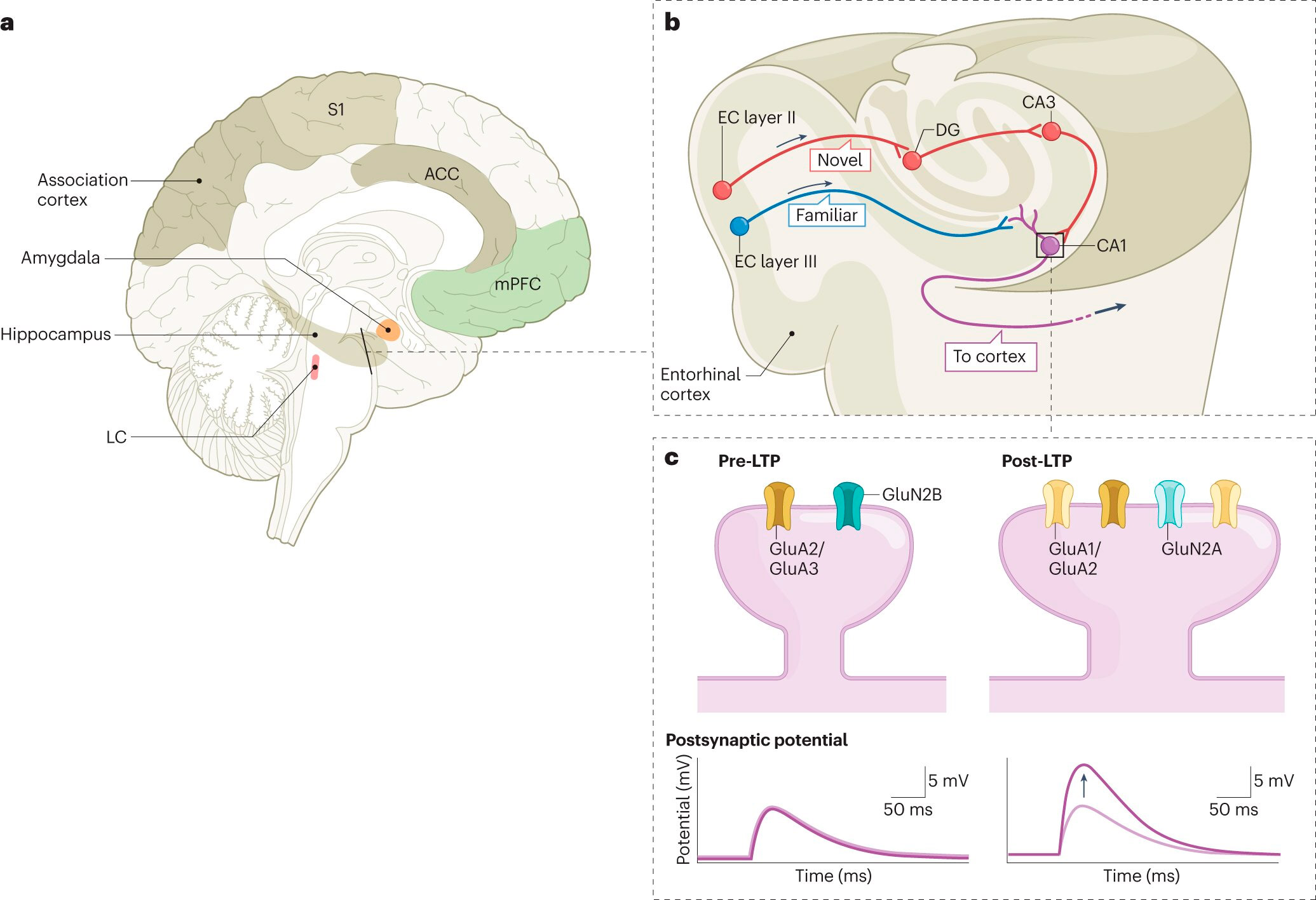

There are two main ways emotional memories are processed during sleep, and they involve the hippocampus and the amygdala.

Our brain stores what we learn every day, with the hippocampus aggregating and cataloging this new information into "novelty" memory. At the same time, if the new experience is emotional, the amygdala is very active and is linked to the autonomic nervous system, causing increased heart rate and other physical reactions.

During REM sleep, the brain reactivates these new memories, playing them out over and over again. But when the noradrenergic and serotonergic systems are turned off, these memories can be moved into "familiar" storage without triggering a physical "fight or flight" response. This is not possible when we are awake or when people with sleep disorders do not get consistent periods of REM sleep.

New Possibilities for Treating Sleep Disorders

Much of what we know about how information is processed in the brain comes from the relatively new field of optogenetics, which enables the activation or inhibition of very specific types of cells in a neural network. This has allowed researchers to see which types of cells and areas of the brain are involved in encoding emotional memories.

Systemic, circuit, and molecular levels of memory trace. Source: Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41583-024-00799-w

"At the neuron, receptor, and neuronal circuit level, our studies have shown that turning off amygdala reactivity and suppressing the autonomic nervous system during REM sleep is critical," says Dr. Wasing.

Creating "good sleepers"

"We know that when people have insomnia or other sleep disorders where they wake up frequently, they are at increased risk for developing mental health problems. Our hypothesis is that these arousals result in the noradrenergic system not being turned off for long periods of time (and maybe even being overactive), and so these people are unable to regulate emotional memories."

"The solution is to try to get a good night's sleep, but how do you do that? We know that two out of three people with insomnia benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI), but this is largely based on subjective assessments. A patient with insomnia after CBTI does not necessarily become a good sleeper, they may still have sleep disturbances, but CBTI helps them cope better with them."

"We have to look critically at the mechanisms that regulate sleep. It's very difficult to target one system because sleep is so dynamic—the noradrenergic system is turned off during REM sleep, but it has to be active during non-REM sleep, so you can't just turn it off for all of sleep."

"We need really creative ideas about how to develop an intervention or a drug that can target these dynamic processes that happen during sleep and allow these systems to normalize. We need to aim for objective improvements in sleep and make people with insomnia good sleepers again."