New publications

Vaccine created to fight HIV may also fight cancer

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

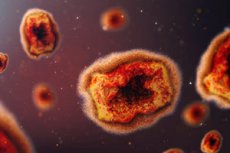

A cytomegalovirus (CMV) vaccine platform developed by Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) is showing promise as a "shield" against cancer. The study's findings were recently published in the journal Science Advances.

Cytomegalovirus, or CMV, is a common virus that infects most people during their lifetime and usually causes mild or no symptoms.

Cancer cells, like many viruses, often evade the immune system by eluding the control of T cells, which help protect the body from infection. The OHSU researchers used CMV to transport cancer-related antigens, which triggered an immune response. This stimulated the production of T cells that specifically target cancer cells and create long-lasting immune system protection.

"We've shown that CMV can induce the production of unusual T cells to cancer antigens, and that these unusual T cells can recognize cancer cells," said Klaus Frue, PhD, a professor in the OHSU Vaccine and Gene Therapy Institute (VGTI). "The idea is that by targeting a specific type of T cell against a cancer that the cancer hasn't seen before, it will have more difficulty evading immune defenses."

Frew and his colleagues Louis Picker, MD, PhD, a professor at VGTI, and Scott Hansen, PhD, an assistant professor at VGTI, have been working on developing this vaccine platform since the early 2000s. In 2016, their OHSU startup company, TomegaVax, was acquired by San Francisco-based Vir Biotechnology. The company is currently testing the platform in a human clinical trial for an HIV vaccine.

Their research initially focused on using the platform as a vaccine against HIV T cells. While initial human clinical trials established the platform’s safety, the researchers have since modified the vaccine to elicit the desired immune responses. They expect the first immune response data from a clinical trial later this year.

Platform expansion

The new study expands on their preclinical studies, showing promise for the CMV vaccine platform against cancer.

The researchers used genetically modified rhesus CMV to induce cancer-specific T cells in rhesus macaques at OHSU's Oregon National Primate Research Center. In previous preclinical studies, they showed that rhesus CMV can be genetically programmed to stimulate T cells differently than conventional vaccines. These T cells recognize infected cells in a unique way.

They sought to answer two questions: Could the Rh-CMV vaccine trigger an unusual immune response to common cancer antigens? And if so, could these unique immune cells recognize and attack cancer cells?

The answer to both questions is yes. The T-cell response to the cancer antigens was similar to their response to viral antigens in both strength and precision. Working with Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, they also found that when an animal model was exposed to a prostate cancer antigen, the T-cells were activated by prostate cancer cells. This suggests that cancer cells can be targeted by this unique immune response.

"Triggering T cells to cancer antigens is not easy because you're trying to trigger an immune response to a self-antigen that the immune system has been trained not to respond to," Frew said. "Overcoming that immune tolerance is the challenge for all cancer vaccines."

Klaus Frue, PhD, a professor at the OHSU Vaccine and Gene Therapy Institute, is investigating the potential of cytomegalovirus-based vaccines. Along with colleagues Louis Picker, MD, and Scott Hansen, PhD, both of VGTI, they have found that their vaccine platform shows promise as a “shield” against cancer.

Hope: Cancer Vaccine

Frew says the vaccine platform’s potential to fight cancer is exciting. Because the T cells induced by CMV vaccines last a lifetime, it could be particularly useful in preventing recurrence of cancers such as prostate or breast cancer. The hope is that if someone has already had prostate cancer, the vaccine will prevent it from coming back.

"If you've had cancer, you spend the rest of your life worrying about it coming back," he said. "So to have a vaccine that can trigger cancer-specific T cells to act as an immune shield that constantly patrols your body and protects you for life is just incredible."

Researchers must first determine whether the results from the animal model can be replicated in humans. CMV is species-specific, so Rh-CMV may not trigger the same immune response in humans. Ongoing clinical trials for HIV will provide early evidence to decide whether further testing and development is worthwhile. Human clinical trials for other pathogens and cancers are on the horizon.