New publications

Scientists have found a way to treat Alzheimer's disease with antibodies

Last reviewed: 30.06.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

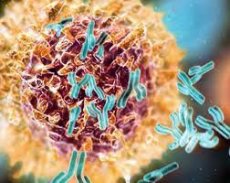

Researchers have found a way to treat Alzheimer's disease using antibodies with dual specificity: one half of the antibody molecule bypasses a checkpoint between the brain and a blood capillary, while the other binds to a protein that causes the death of brain neurons.

Scientists at the biotech company Genentech know how to get into the brain through the blood vessels. At first glance, there is no problem: the brain is supplied with oxygen and nutrients via a regular network of capillaries. But over a hundred years ago, physiologists discovered the so-called blood-brain barrier between the brain and the circulatory system. Its function is to maintain biochemical constancy in the brain: no random changes (for example, in the ionic composition or pH level of the blood) should affect the functioning of the brain; neurotransmitters that control other organ systems should not penetrate the brain; especially since the brain is closed to most large molecules, such as antibodies and bacterial toxins (not to mention the bacteria themselves). The cells of the capillary walls in the brain have extremely tight junctions and a number of other features that protect the brain from unwanted penetration. As a result, the concentration of the same antibodies here is a thousand times less than in the bloodstream.

But for the treatment of many diseases, it is important to deliver drugs to the brain. And if this drug is such large proteins as antibodies, then the effectiveness of the treatment is sharply reduced. Meanwhile, many hopes are associated with artificial antibodies, including among those who study Alzheimer's disease. This disease is accompanied by the formation of amyloid masses in neurons - in other words, a "sediment" of incorrectly packed protein molecules that destroys nerve cells. Among the proteins responsible for the formation of amyloids in Alzheimerism, β-secretase 1 is the most popular, which is most often chosen as a target for therapy.

So, to break through the blood-brain barrier, the researchers created bidirectional antibodies. One part of the molecule recognized the enzyme β-secretase, the other - the protein transferrin in the walls of blood vessels. The latter is a receptor responsible for the flow of iron ions into the brain. According to the scientists' idea, the antibodies grabbed onto transferrin, which transferred them to the brain: thus, the barrier between the brain and the circulatory system, so to speak, "was left in the cold."

At the same time, the researchers had to solve another problem, this time related to antibodies themselves. The strength with which antibodies bind to their target molecule - the antigen - is called affinity. Usually, the higher the affinity, the better the antibody. From a medical point of view, the most strongly binding antibodies are the most effective. But in this case, the scientists had to reduce the binding strength of the created antibodies to transferrin, otherwise they would tightly bind to the carrier and get stuck at the threshold. The strategy paid off: in experiments on mice, just one day after the animals were injected with these antibodies, the amount of amyloidogenic proteins in the brain fell by 47%.

In their work, the researchers went against the rules that say antibodies must be strictly specific and have high affinity, that is, very tightly bind only one target. But it is weakly binding antibodies with multiple specificities that can help in the treatment of not only Alzheimer's disease, but also in cancer therapy. Cancer cells carry proteins on their surface that can be recognized by antibodies, but these same proteins are also produced by other cells, as a result of which antibodies against cancer cells often kill healthy cells as well. Multispecific antibodies could recognize a combination of surface proteins characteristic of cancer cells, and a set of such proteins would allow antibodies to tightly bind only to cancer cells, and not to normal cells, on which they simply would not hold.

Skeptics from competing companies say that due to their low specificity, the antibodies developed by Genentech will not be used clinically, since this would require injecting huge quantities of them into humans. The authors, however, claim that this will not be necessary: our antibodies last much longer than those of mice, and the excess of them that had to be injected into experimental animals is simply a specificity of the “mouse” system...

[

[