New publications

Scientists have discovered the memory of the immune system

Last reviewed: 01.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

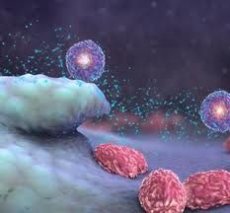

The immune system has a type of cell that reminds it not to attack its own cells, tissues and organs, UCSF researchers have found.

The UCSF scientists say the discovery could lead to new strategies for treating a wide range of autoimmune diseases - in which the immune system attacks and destroys cells within the body - and for preventing transplant rejection.

The cells identified by UCSF scientists circulate in the blood and are copies of memory cells that protect against pathogens after vaccination or repeated exposure to the same pathogen.

To determine the role of memory cells called activated T cells in the immune system, UCSF immunologist and chair of pathology Aboul Abbas used mice with an autoimmune disease.

He found that over time, tissues in the body - in the study, the skin - protect themselves from autoimmune attacks by activating a small subset of regulatory T cells.

Autoimmune diseases, ranging from mild to severe, affect approximately 50 million Americans. For decades, immunologists believed that these diseases developed because of a defect in the functioning of immune cells known as lymphocytes, including the cells that produce antibodies to pathogens.

In autoimmune diseases, lymphocytes can be directed against their own proteins. For example, in multiple sclerosis, lymphocytes produce antibodies that attack proteins in the myelin sheath that surrounds nerves; in lupus, they produce their own DNA.

But in many cases, autoimmune diseases may be linked to an abnormal response by T-regulatory cells, UCSF researchers say. In recent years, immunologists have come to understand the important role of T-regulatory cells, which are associated not only with dampening the immune response during recovery from infection but also in preventing autoimmune reactions.

UCSF researchers wanted to study how an autoimmune response might self-limit or diminish over time. Doctors noticed that in many cases of autoimmune diseases, the first immune attack on organs tends to be more aggressive than later outbreaks of the immune response.

UCSF scientists created a genetically engineered strain of mice in which they could turn on or off the production of a protein in the skin called ovalbumin that would trigger an autoimmune response.

The presence of the protein also stimulated the activation of T-regulatory cells. When the scientists increased ovalbumin production again in mice, it caused a weak autoimmune response, due to the presence of already activated T-cells.

Currently, T-regulatory cells are already being studied in therapies aimed at preventing the rejection reaction of transplanted organs.

The discovery of long-lived memory cells in the T-regulatory cell population points to enormous promise in using specialized memory cells to prevent attacks on specific molecular targets that immunologists call "antigens."

Since the role of activated T-regulatory memory cells has not been previously recognized, this study may provide a strong impetus for the initiation of clinical trials of specific immunotherapy in multiple sclerosis and type 1 diabetes.

[

[