New publications

Reducing infant mortality extends the lives of mothers

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

A significant decline in infant mortality in the 20th century added a full year to women's life expectancy, according to a new study.

"I imagined what the U.S. maternal population looked like in 1900," said Matthew Zipple, a doctoral student in the Klarman Program in Neuroscience and Behavior in the College of Arts and Sciences and author of the paper, "Reducing Infant Mortality Extends Maternal Life," published in the journal Scientific Reports.

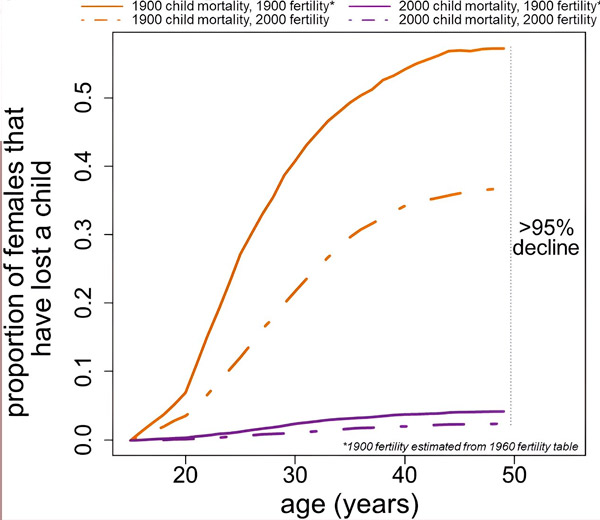

"This population consisted of two roughly equal-sized groups: one group of mothers who had lost their children and one group of mothers who had not," Zipple said. "Compared to today, when child loss has become much less common, almost all of these women who had lost their children have now moved into the non-grieving category."

Several studies show that mothers are more likely to die in the years after a child's death, Zipple said. The effect does not hold for fathers.

Using mathematical modeling based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), he calculated how the absence of grief affects the life expectancy of modern mothers in the United States. He estimated that reducing maternal grief adds an average of one year to a woman’s life expectancy.

As a doctoral student studying the links between maternal fitness and offspring, Zipple discovered a pattern of maternal death following offspring death in non-primates. In animals, this effect was explained by mothers being in poor health and less able to care for their offspring.

But in humans, the same sequence of events—offspring death followed by maternal death—has been interpreted differently in studies with a human focus. Instead, epidemiologists and public health researchers conclude that the physical and psychological costs of the trauma of losing a child make mothers more likely to die.

In the article, Zipple cites several studies that causally link the death of a child to an increased risk of maternal death. The largest is a study of mothers in Iceland over a 200-year period, spanning different levels of access to health care and industrialization. It controls for genetics by comparing siblings and shows that grieving fathers are no more likely to die than non-grieving fathers in the years following the death of their child.

Another study in Sweden shows that mothers are at higher risk of dying on and around the anniversary of their child's death than at other times. According to various studies, common causes of death among grieving mothers include heart attack and suicide.

"There's a huge peak in mortality risk right around the week around the anniversary," Zipple said. "It's hard to come to any conclusion other than that it's caused by the memory of the event."

Life expectancy for women after age 15 increased by about 16 years between 1900 and 2000, Zipple found from the CDC data used in the study. His calculation attributes one year, or about 6 percent, of that increase to the significant decline in infant mortality over the 20th century.

"One of the most horrific things you can imagine is losing a child. And we've been able to reduce the incidence of that in our community by over 95%. That's amazing. That's something to celebrate," Zipple said.

"It's easy to overlook the progress that occurs over the course of a century because it extends beyond the lifetime of any one individual. But this increase in overall life expectancy over the last 100 years has improved the living conditions and experiences of people like never before."

Priorities for the Future

The research also helps set priorities for improving the future, Zipple said. Many countries today have child mortality rates similar to those in the United States in 1900. Investing in reducing child mortality everywhere helps not just children but entire communities.

"The child is the core of the community," Zipple said. "Protecting children from mortality has cascading positive impacts that start with mothers but probably don't end there."