New publications

Protein responsible for genetic inflammatory disease identified

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

A team of researchers led by Dr. Hirotsugu Oda from the CECAD Cluster of Excellence for Aging Research at the University of Cologne has discovered the role that a certain protein complex plays in some forms of immune dysregulation. This result may lead to the development of new therapeutic approaches aimed at reducing autoinflation and “restoring” the immune system of patients suffering from a genetic dysfunction of this protein complex.

The study, "Biallelic human SHARPIN loss of function induces autoinflammation and immunodeficiency," was published in the journal Nature Immunology.

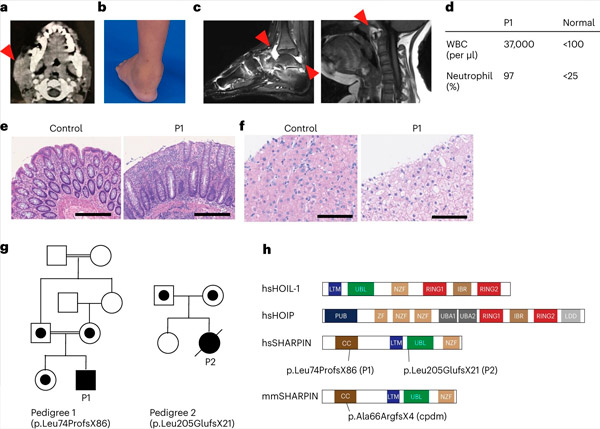

The linear ubiquitin-assembling complex (LUBAC), composed of the proteins HOIP, HOIL-1, and SHARPIN, has long been recognized for its critical role in maintaining immune homeostasis. Previous studies in mice have shown the severe consequences of SHARPIN loss, leading to severe dermatitis due to excessive skin cell death. However, the specific health consequences of SHARPIN deficiency in humans have remained unclear.

The research team reported for the first time two people with SHARPIN deficiency who exhibit symptoms of autoinflation and immunodeficiency, but unexpectedly do not show dermatological problems as they did in mice.

Upon further investigation, these individuals were found to have an impaired canonical NF-κB response, an important immune response pathway. They also had increased susceptibility to cell death induced by members of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily. Treatment of one SHARPIN-deficient patient with anti-TNF therapy, which specifically inhibits TNF-induced cell death, resulted in complete resolution of autoinflation at the cellular level and in clinical presentation.

The study shows that excessive and uncontrolled cell death plays a critical role in genetic human inflammatory diseases. Oda's team added SHARPIN deficiency as a new member of a group of genetic human inflammatory diseases they propose to call "inborn errors of cell death."

Protection against immune dysregulation The study was initiated in the laboratory of Dr. Dan Kastner at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the United States. Scientists there had the opportunity to observe one patient with a childhood-onset of unexplained episodes of fever, arthritis, colitis, and immune deficiency.

After obtaining informed consent, they performed exome sequencing on the patient and his family members and found that the patient had a devastating genetic variant in the SHARPIN gene that led to undetectable levels of the SHARPIN protein. They also found that the patient’s cells showed an increased propensity to die in both cultured cells and in biopsies of the patient.

SHARPIN deficiency in humans causes autoinflammation and liver glycogenosis. Source: Nature Immunology (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41590-024-01817-w

The team also found that the development of lymphoid germinal centers – specialized microstructures in the adenoids that are critical for the maturation of our immune system’s B cells and, therefore, for antibody production – was significantly reduced due to increased B cell death. These findings explain the patients’ immunodeficiency and highlight the important role of LUBAC in maintaining immune homeostasis in humans.

"Our study highlights the critical importance of LUBAC in protecting against immune dysregulation. By elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying LUBAC deficiency, we pave the way for new therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring immune homeostasis," said Oda, lead author of the study.

He added: "One of the patients with SHARPIN deficiency had been wheelchair-bound for years before we first saw him. His ankles were inflamed and it was too painful to walk. The genetic diagnosis allowed us to target the correct molecular pathway underlying his conditions."

Since the patient began receiving anti-TNF therapy, he has been symptom-free for nearly seven years. “As a clinician and scientist, I am pleased to have the opportunity to positively impact one patient’s life through our research,” Oda concluded.