New publications

A perspective on the growing threat of monkeypox virus

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

In a paper published in Nature Microbiology, Bernard Moss of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases' Laboratory of Viral Diseases summarizes and discusses the available scientific knowledge about MPX virus, the cause of the zoonotic disease smallpox (formerly known as "monkey pox"). Given its sudden and alarming global increase in prevalence (from 38 reported cases between 1970-1979 to more than 91,000 cases between 2022-2023) and the first reported documentation of sexual transmission (primarily among men who have sex with men [MSM]), the disease is now included in World Health Organization (WHO) External Situation Report #30, highlighting the need to better understand the virus to combat new cases.

This review study examines the biology and genetics of MPXV, its epidemiology, potential animal reservoirs, functional genetics, and the potential for using animal models in research to limit the spread of the disease. The article highlights the lack of current scientific knowledge in this area and the need for additional research to elucidate the mechanisms of disease interaction with humans, with a focus on interpreting the mechanisms of action of the three known MPXV types (1, 2a, and 2b).

What is MPXV and why are doctors concerned about this condition?

Monkeypox virus (MPXV) is a zoonotic disease agent of the poxvirus family, belonging to the genus Orthopoxvirus (subfamily Chordopoxvirinae). It is closely related to variola virus (VARV, the causative agent of smallpox), cowpox virus (CPXV), and ectomelia virus (ECTV, the causative agent of the rodent disease mousepox). MPXV was first isolated and described from captive cynomolgus monkeys in 1958, and human infections were identified in central and western Africa in the early 1970s.

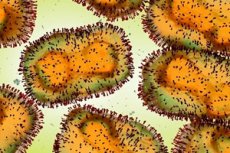

Although not as clinically virulent as the now-eradicated smallpox, smallpox is known for its symptoms of erythematous skin lesions, high fever, vesiculopustular eruptions, and lymphadenopathy. The case fatality rate for the disease has been reported to range from <3.6% (West Africa) to ~10.6% (Central Africa). Alarmingly, the number of reported smallpox cases has increased dramatically, from 38 cases between 1970-79 to over 91,000 cases between 2022-23. Previously confined to Central and West Africa, the disease has now been identified in the United Kingdom, Israel, the United States, Singapore, and (as of November 2023) 111 countries worldwide.

Increasing global prevalence, detection of human-to-human transmission, and increasing global mortality (167 confirmed deaths between 2022-23) have prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare MPXV a "public health emergency of international concern" and include it in External Situation Report #30. Unfortunately, despite the long history of the disease, research on MPXV remains scarce. This review aims to synthesize, collect, and discuss the available scientific literature on the epidemiology of the three known MPXV clades to provide clinicians and policymakers with the information needed to contain the spread of the disease and potentially achieve eradication similar to that of smallpox.

Biology, Genetics and Functional Genetics MPXV

Like all other smallpox viruses, MPXV is a large, double-stranded DNA virus that utilizes the cytoplasm of its (usually mammalian) host cells for survival and replication. Given the paucity of MPXV-specific studies, much of our understanding of MPXV biology is based on observations of the biology, epidemiology, and functional genetics of the vaccine virus (VACV). Briefly, the virus first binds to a host cell, fuses with the cell membranes, and then releases its core into the cell cytoplasm. This release triggers the transcription of viral mRNAs, which encode 1. Enzymes for viral genome replication, 2. Intermediate transcription mRNAs, and 3. Surface proteins for host immune evasion and defense.

"The rate of virus evolution is determined primarily by the mutation rate. The poxvirus proofreading DNA polymerase has a low error rate, and analyses of VARV in humans and MPXV in chimpanzees indicate 1 × 10−5 and 2 × 10−6 nucleotide substitutions per site per year, respectively. This rate is significantly lower than the 0.8–2.38 × 10−3 and 2 × 10−3 nucleotide substitutions per site per year estimated for SARS-CoV-223 and influenza virus24, respectively. In vitro studies suggest that transient gene duplications (known as the accordion model) may precede further mutational events in orthopoxviruses, allowing accelerated adaptation to host antiviral defenses."

Recent genetic studies have shown that the previously assumed single MPXV strain is actually composed of three clades – clade 1, mostly found in Central African countries, and clades 2a and 2b, mostly found in West Africa. Genomic differences between clades range from 4-5% (clade 1 vs. clades 2a/2b) and ~2% between clades 2a and 2b.

"Most differences between clades are nonsynonymous nucleotide polymorphisms and may potentially affect replication or host interaction. However, almost all genes in clades I, IIa, and IIb appear intact, as indicated by the conserved length of host interaction genes."

Functional genetics studies have shown that deletions significantly reduce viral replication in non-human primate (NHP) models, but this area of science is still in its infancy and more research is needed before genetic interventions can be used to combat MPXV.

Epidemiology and animal reservoirs

Prior to the recent global outbreaks of 2018-19 and 2022-23, cases of MPOX were largely confined to Central and West Africa. However, due to civil conflicts in the region, lack of medical testing facilities in remote rural areas, and misidentification of MPOX as smallpox before its eradication, estimates of MPOX prevalence are believed to be underestimates.

"Reporting of cases, which is required in the DRC but not confirmed, showed an upward trend in cases: from 38 in 1970-1979 to 18,788 in 2010-2019 and 6,216 in 2020. From 1 January to 12 November 2023, 12,569 cases were reported. Fewer cases have been reported in other Central African countries, including the Central African Republic, Cameroon, Congo, Gabon and South Sudan, where reporting is not mandatory. Primary zoonotic infection is thought to occur through hunting, processing or consumption of wild animals in tropical forests."

Animal reservoirs are considered the most common route of MPXV transmission, with men who have sex with men (MSM) being the next most common. Although captive Asian monkeys were the source of the first MPXV identified, studies of wild monkeys have failed to identify infected populations in Asia. In contrast, large populations of rodents (usually arboreal), monkeys, and bats infected with the disease have been found in the lowlands of Central and West Africa. The highest prevalence has been found in rodents of the genera Funisciuris and Heliosciuris, which are considered the main zoonotic reservoirs of the disease.

Despite several decades since MPXV’s discovery, our knowledge of the disease and its viral mechanisms remains woefully inadequate. Future research into MPXV biology, particularly its host immune evasion and interactions, would help curb its transmission, particularly in Africa.

"More equitable distribution of vaccines and therapeutics, a better understanding of MPXV epidemiology, identification of animal reservoirs of MPXV that can transmit MPXV to humans, and a better understanding of human-to-human transmission are necessary if we are to better manage or even prevent future MPXV outbreaks."