New publications

New research explores whether adequate sleep can help prevent osteoporosis

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

At the University of Colorado Department of Medicine's annual Research Day on April 23, faculty member Christine Swanson, MD, MS, described her National Institutes of Health-funded clinical research on whether getting enough sleep can help prevent osteoporosis.

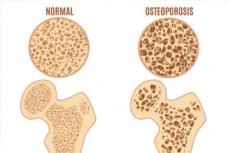

"Osteoporosis can occur for many reasons, such as hormonal changes, aging, and lifestyle," said Swanson, an associate professor in the division of endocrinology, metabolism, and diabetes. "But some patients I see have no explanation for their osteoporosis.

So it's important to look for new risk factors and look at things that change over the course of life, like bones - sleep is one of them," she added.

How Bone Density and Sleep Change Over Time

In the early and mid-20s, people reach what's called peak bone mineral density, which is higher in men than in women, Swanson said. That peak is one of the main determinants of fracture risk later in life.

After reaching this peak, a person's bone density remains roughly stable for several decades. Then, as women enter menopause, they experience accelerated bone loss. Men also experience a decrease in bone density as they age.

Sleep patterns also change over time. As people age, total sleep time decreases and the composition of sleep changes. For example, sleep latency, which is the time it takes to fall asleep, increases with age. On the other hand, slow wave sleep, which is deep, restorative sleep, decreases with age.

"And it's not just the duration and composition of sleep that changes. Circadian phase preferences also change across the lifespan in men and women," Swanson said, referring to people's preferences for when they go to bed and when they wake up.

How is sleep related to our bone health?

The genes that control our internal clocks are present in all our bone cells, Swanson said.

As these cells reabsorb and form bone, they release certain substances into the blood that allow us to estimate how much bone turnover is occurring at any given moment."

Christine Swanson, MD, MS, Lecturer, University of Colorado School of Medicine

These markers of bone resorption and formation follow a circadian rhythm. The amplitude of this rhythm is greater for markers of bone resorption — the process of breaking down bone — than for markers of bone formation, she said.

"This rhythmicity is likely important for normal bone metabolism and suggests that disruptions to sleep and circadian rhythms may directly impact bone health," she said.

Study explores link between sleep and bone health

To further explore this link, Swanson and colleagues examined how bone turnover markers respond to cumulative sleep restriction and circadian disruption.

In this study, participants were kept in a fully controlled, stationary environment. Participants were unaware of the time and were placed on a 28-hour schedule instead of a 24-hour day.

"This circadian disruption is designed to mimic the stresses experienced while working night shifts and is roughly equivalent to flying west across four time zones every day for three weeks," she said. "The protocol also resulted in reduced sleep time in the participants."

The research team measured bone turnover markers at the beginning and end of the intervention and found significant adverse changes in bone turnover in men and women in response to sleep and circadian rhythm disruptions. Adverse changes included decreases in bone formation markers that were significantly greater in younger adults of both sexes compared to older adults.

In addition, a significant increase in a bone resorption marker was found in young women.

If a person forms less bone while resorbing the same amount — or more — over time, that can lead to bone loss, osteoporosis and an increased risk of fractures, Swanson said.

"Gender and age may play an important role, with young women potentially most susceptible to the adverse effects of poor sleep on bone health," she said.

Research in this area continues, she added.