New publications

Microscopic plastic particles may increase the risk of developing serious diseases

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

People may be at increased risk of developing cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and chronic lung disease as rising levels of micro- and nanoplastics (MnPs) are absorbed into the human body worldwide, according to a new study.

Some of these non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are associated with inflammatory conditions in body organs, with fine particles increasing the uptake of MnPs and their leucates in the digestive and respiratory systems, potentially increasing the risk and severity of NCDs in the future.

The study found that the concentration of MnPs in the faeces of infants was significantly higher than that of adults, possibly because plastic is widely used in the preparation, serving and storage of infant food. The behaviour of young children, such as the habit of putting objects in their mouths, may also be a factor.

Publishing their findings in the journal Cell Reports Medicine, the international team of researchers calls for a global, integrated One Health approach to human and environmental health research to identify the mechanisms behind rising human exposure to MnPs and their association with NCD.

Lead author Professor Stefan Krause, from the University of Birmingham, said: "Plastic pollution has increased globally, making it critical to understand the overall health risks associated with exposure to MnPs.

"We must tackle this pollution at its source to reduce further emissions, as the global spread of MnPs that has already occurred will remain a concern for many years to come. To do this, we need a systematic study of the environmental factors that influence human exposure to MnPs and their impact on the prevalence and severity of major NCDs such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and chronic lung disease."

The researchers point out that the relationship between MnPs and NCD is similar to that of other particles, including natural sources such as pollen or man-made pollutants such as diesel exhaust, all of which act in similar biological ways.

The body views them as foreign objects that trigger the same defense mechanisms, which poses the risk of overloading the body's defense systems and increasing the frequency and severity of NCDs.

Hypothetical mechanisms for MnPs uptake across human biological barriers include the olfactory bulb, the air-lung barrier, and the gastrointestinal tract. Larger particles have been shown to be absorbed via the gastrointestinal tract, while smaller particles (nanoparticles) can cross the blood-brain barrier. MnPs taken up via the lungs and gastrointestinal tract reach the general circulation and can reach all organs.

The incidence of NCDs is increasing worldwide, and the four main types of these diseases are responsible for 71% of all annual deaths, creating a projected economic loss of more than $30 trillion over the next two decades.

Co-author Semira Manaseki-Holland, from the University of Birmingham, said: "We need to better understand how MnPs and NCD interact to advance global prevention and treatment efforts in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals to reduce premature mortality from NCD and other inflammatory diseases by 2030.

"This is particularly important in low- and middle-income countries where the prevalence of NCD is increasing and plastic pollution and exposure levels are high. Whether we are indoors or outdoors, MnPs are likely to increase global health risks."

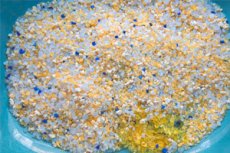

Global pollution trends show that micro- and nanoplastic particles are now ubiquitous. MnPs have been detected in lungs, blood, breast milk, placenta and stool samples, confirming that the particles are entering the human body from the environment.

People are exposed to MnPs in outdoor and indoor environments through food, beverages, air, and many other sources, including cosmetics and personal care products.

MnPs have been found in fish, salt, beer, plastic drink bottles, or in the air where they are released from synthetic clothing, plastic bedding, carpets, or furniture. Other sources include fertilizers, soil, irrigation, and absorption into crops or produce.

Human exposure to MnPs varies significantly depending on location and mechanism of exposure, with indoor MnPs pollution "hot spots" containing up to 50 times more particles than outdoors having been demonstrated.

Co-author Professor Isoult Lynch, from the University of Birmingham, added: "We need to understand the human health risks associated with MnPs and to do this we need to understand the environmental factors that influence individual exposure. This will require close collaboration between environmental and medical scientists."