Scientists have deprived brain cancer cells of the ability to survive using a new method

Last reviewed: 14.06.2024

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

When a race car's brakes are cut off, it quickly crashes. Dr. Barak Rotblat wants to do something similar with brain cancer cells: turn off their ability to survive a lack of glucose. It aims to speed up the work of tumor cells so that they die just as quickly. This new approach to treating brain cancer builds on a decade of research in his laboratory.

New discoveries

Dr. Rotblat, his students and co-principal investigator Gabriel Leprivier from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University Hospital Düsseldorf published their findings last week in the journal Nature Communications.

Until now, it was believed that cancer cells were primarily focused on growth and rapid reproduction. However, tumors have been shown to have less glucose than normal tissues.

If cancer cells are entirely focused on rapid proliferation, then they should be more dependent on glucose than normal cells. However, what if their absolute priority is survival rather than exponential growth? Then starting growth with a lack of glucose can lead to the cell running out of energy and dying.

Prospects for personalized medicine

“This is an interesting discovery that we came to after a decade of research,” explains Dr. Rotblat. “We can target cancer cells exclusively without affecting normal cells, which will be an important step forward towards personalized medicine and therapies that do not affect healthy cells in the same way as chemotherapy and radiation.”

“Our discovery of glucose fasting and the role of antioxidants opens a therapeutic window for creating a molecule that could treat glioma (brain cancer),” he adds. Such a therapeutic agent may also be applicable to other types of cancer.

Research and its results

Rotblat and his students, Dr. Tal Levy and Dr. Khaula Alasad, began by considering how cells regulate their growth based on available energy. When there is enough energy, cells store fat and synthesize a lot of proteins to store energy and grow. When energy is limited, they must stop this process so as not to exhaust their resources.

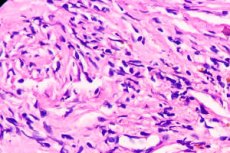

Tumors are mainly in a state of glucose deficiency. Researchers have begun looking for molecular brakes that allow cancer cells to survive glucose deficiency. If they can be turned off, the tumor will die, and ordinary cells that do not lack glucose will remain undamaged.

The mTOR pathway and the role of 4EBP1

Rotblat and his team studied the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, which contains proteins that sense the energy state of the cell and regulate its growth. They found that a protein in the mTOR pathway known as 4EBP1, which inhibits protein synthesis when energy levels drop, is essential for the survival of human cells, mice and even yeast when starved of glucose.

They demonstrated that 4EBP1 does this by negatively regulating levels of a key enzyme in the fatty acid synthesis pathway, ACC1. This mechanism is used by cancer cells, especially brain cancer cells, to survive in tumor tissue and create aggressive tumors.

Development of new treatment

Dr. Rotblat is now working with BGN Technologies and the National Institute of Biotechnology in the Negev to develop a molecule that will block 4EBP1, causing glucose-starved tumor cells to continue synthesizing fat and exhaust their resources when glucose is deficient.