New publications

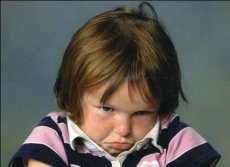

Scientists have begun to develop a cure for aggression

Last reviewed: 01.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Pathological fits of rage can be blocked. This was stated by scientists from the University of Southern California (USC University) after an experiment on mice. The specialists managed to identify a neurological factor of aggression - a receptor in the brain (NMDA), which does not work properly in excessively angry rodents. When it was turned off, their excessive aggression disappeared. People have the same receptor. The authors hope that their discovery will help in developing a new method of treating aggression, which often accompanies Alzheimer's disease, autism, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, writes Science Daily.

"From a clinical and social point of view, reactive aggression is quite a serious problem. We want to find 'tools' that will help reduce impulsive violence," says Marco Bortolato, the study's author and a researcher at the USC School of Pharmacy.

According to the scientist, with a certain predisposition to pathological aggression, the following are observed: low levels of the enzyme monoamine oxidase A (MAO A), a strong reaction to stress. "The same type of mutation that we found in mice is associated with aggressive behavior in humans, especially in criminals. The combination of low levels of MAO A and harsh treatment in childhood is fatal and leads to the manifestation of inhumanity in adulthood," says M. Bortolato.

The researchers experimented on hyper-aggressive rodents lacking the enzyme and found that the receptor in their prefrontal cortex required strong electrical stimulation, and even if activated, it would only work for a short time.

"Our discovery has great potential, because we have learned that blocking this receptor reduces aggression. Whatever a person's behavior, living conditions, and environment, in the future it will be possible to control the manifestations of his pathological anger," comments M. Bortolato. He noted that the NMDA receptor plays a key role in the brain's recording of multiple simultaneous streams of sensory information. Now a team of specialists is studying the possible side effects of drugs that reduce the activity of this receptor.

"Aggressive behavior has serious socioeconomic consequences. Our task is to understand what pharmacological agents and treatment regimens should be used to influence the receptor," the scientist concluded.

[

[