New publications

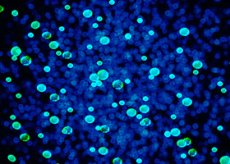

Microbes "rule" human genes

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Bacteria in the intestines inhibit the function of enzymes responsible for managing DNA storage.

People have long known that digestive microbes have a direct effect on metabolic processes, immune protection, and an indirect effect on brain activity. They probably make their own adjustments to gene structures: for some reason, some genes are activated, while others are blocked. How do bacteria do this?

Experts from Babraham University (UK) claim that digestive microorganisms change gene activity using short fatty acids, such as butyric acid. These acids inhibit the action of specific enzymes, such as histone deacytelases, which control human genes.

The acids cooperate with other protein structures called histones. The latter act as DNA "keepers". The interaction of histones with DNA is constant, but in some cases they "pack" DNA too tightly or, conversely, too weakly. This complicates the reading of genetic information by a specific molecular apparatus.

The strength with which histones “pack” DNA depends on chemical modifications. Each cellular structure has a number of enzymes that mark histones with certain markers, which forces them to “pack” DNA with varying degrees of density.

Among these enzymes are the histone deacytelases that we are already familiar with. Their job is to remove markers from histones. However, their functionality also depends on many factors, such as molecular structures that turn off these enzymes. Research has shown that intestinal microbes can use fatty acids to turn off one type of histone deacytelase. As a result, histones continue to remain “marked.” The bond between “marked” histones and DNA differs from the bond between normal histones – they affect gene activity differently.

What can this lead to? Previous studies have shown that high activity of the enzyme increases the risk of developing a malignant tumor of the colon: the enzyme affects gene activity in the epithelial structures of the intestine so much that the latter are transformed and become malignant. New experiments on rodents have shown that if mice are "cleaned" of intestinal bacteria, they experience a marked increase in the activity of the same enzyme. From this we can conclude that intestinal microbes protect humans from malignant processes in the colon. Although this statement still needs to be confirmed by other studies.

In conclusion, it should be said that microbes synthesize much more important short fatty acids if a person eats more plant foods (mainly fruits and vegetables). In other words, for the quality work of microorganisms in the digestive system, they need to be regularly supplied with plant products. This statement can be an additional strong argument: it is necessary to eat healthy food with sufficient consumption of fruits and vegetables.

The study is described in detail in Nature Communications.