New publications

Metabolic differences in muscle mass between men and women may explain different diabetes outcomes

Last reviewed: 15.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

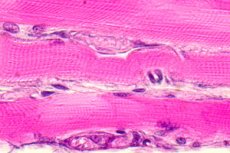

The skeletal muscles of men and women process glucose and fat differently. A study conducted by the University Hospital Tübingen, the Helmholtz Institute for Diabetes and Metabolic Disease Research in Munich and the German Diabetes Research Center (DZD) e.V. provides the first comprehensive molecular assessment of these differences. The results, published in the journal Molecular Metabolism, may explain why metabolic diseases such as diabetes manifest differently in women and men – and why they respond differently to physical activity.

Skeletal muscle is much more than just a “motor of movement.” It plays a key role in glucose metabolism and, therefore, in the development of type 2 diabetes. This is because about 85% of insulin-dependent glucose uptake occurs in muscle.

This means that if muscle cells become less sensitive to insulin (such as in insulin resistance), glucose is less readily absorbed from the blood. Physical activity directly counteracts this process.

Men's and women's muscles work differently

The extent to which muscles work differently in men and women has long been underestimated. That's exactly what scientists led by Simon Dreher and Cora Weigert have now investigated. They examined muscle biopsies taken from 25 healthy but overweight adults (16 women and 9 men) in their 30s.

The subjects had no previous history of regular physical activity. For eight weeks, they completed an aerobic exercise program for one hour three times a week, which included 30 minutes of cycling and 30 minutes of walking on a treadmill.

Muscle samples were taken before training, after the first session, and at the end of the program. Using modern molecular biology techniques, including epigenome, transcriptome, and proteome analysis, the team examined sex differences at multiple levels.

Men respond to stress with greater stress

The result: The first workout induced a stronger stress response at the molecular level in the men, which was reflected in increased activation of stress genes and increased levels of the muscle protein myoglobin in the blood. In addition, the men's muscles showed a pronounced pattern of so-called fast-twitch muscle fibers, which are designed for short-term, intense exercise and prefer to use glucose as an energy source.

Women had significantly more proteins responsible for the absorption and storage of fatty acids, indicating more efficient use of fats. After eight weeks of regular aerobic exercise, the muscles of both sexes became more similar, and the specific differences in muscle fibers decreased. At the same time, both women and men had more proteins that help use glucose and fats in the mitochondria, the "power plants" of cells.

“These adaptations indicate an overall improvement in metabolic performance, which may help reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes,” says Weigert. “In the future, our new data may help better predict individual diabetes risks and more accurately tailor physical activity recommendations for women and men separately.”

What's next?

Scientists now want to study the role of sex hormones such as estrogen and testosterone in these differences and how hormonal changes in old age influence the risk of metabolic diseases.