New publications

Researchers have shown for the first time in detail how HIV-1 viral cores enter the cell nucleus

Last reviewed: 27.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

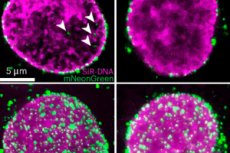

In a recent landmark study, scientists have uncovered how HIV-1 penetrates the cell’s nuclear barrier – a discovery that could change the way antiviral strategies are approached. The study, led by Professor Peijun Zhang, Director of eBIC at Diamond, used cutting-edge cryo-electron microscopy to image HIV-1 viral nuclei during nuclear entry – an elusive but critical step in the virus’s life cycle.

The findings, published in Nature Microbiology, were made possible by the cryo-EM capabilities at eBIC, the UK’s National Electronic Bio-Imaging Centre. Researchers from Professor Zhang’s lab at Oxford University used a technique called cell permeabilisation to make the cell membrane permeable without destroying the cell itself. They were able to simulate the process of HIV infection in human cells and capture almost 1,500 viral nuclei embedded in the cell nucleus.

The study showed that the success of HIV-1 in entering the nucleus depends on the shape and flexibility of its viral cores, the adaptability of the nuclear pore complex (NPC), and host factors such as CPSF6.

CPSF6 is a host cell protein that plays a key role in the early stages of HIV-1 infection, particularly during viral entry into the nucleus and integration into the host genome.

Previously, it was thought that the nuclear pore complex was a rigid, fixed structure that only allowed certain molecules to pass through. However, the study showed that the nuclear pores are much more flexible – they can expand and change shape to allow HIV particles (viral cores) to pass through.

However, not all viral cores make it into the nucleus: if the core is too fragile or cannot interact with the CPSF6 protein, it gets stuck in the pore or remains outside. This means that nuclear pores are not just passive “doors” but active players in deciding which viruses can enter. This is a fundamentally new understanding of HIV infection and how the virus interacts with our cells.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) remains one of the most serious threats to human health since its first reported case in 1981, causing more than 42 million deaths and over 1 million new infections annually. These findings not only advance our understanding of HIV-1, but also demonstrate the power of in situ structural biology to illuminate complex cellular processes.

This work represents a significant breakthrough in visualising HIV at its critical stage and understanding how it could potentially be stopped.