New publications

Hope for a cure for deadly visceral leishmaniasis

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

The discovery by Simone Steger's team could help develop a treatment for the most serious form of leishmaniasis. Leishmaniasis is a tropical disease that is affecting an increasing number of people worldwide. Between 700,000 and 1 million new cases are registered each year. The causative agent is a protozoan parasite of the genus Leishmania, which is transmitted to humans through the bite of a mosquito. Leishmaniasis includes three clinical forms, of which the visceral form is the most serious.

If left untreated, visceral leishmaniasis is almost always fatal. Most cases occur in Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Nepal and Sudan.

Professor Steger from the National Institute for Scientific Research (INRS) and her team, in collaboration with other researchers from INRS and McGill University, have observed a surprising immune mechanism associated with chronic visceral leishmaniasis. This discovery could be an important step towards a new therapeutic strategy for this disease. Their findings are published in the journal Cell Reports.

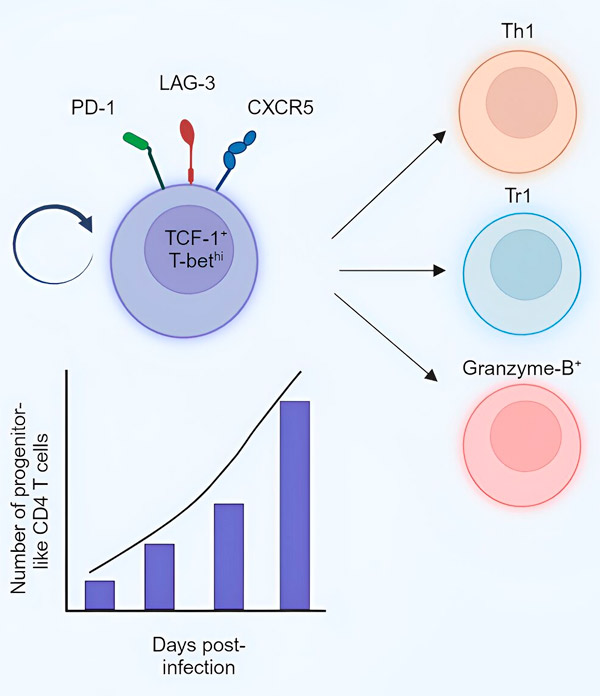

In many infections, CD4 T cells play a key role in the host's defense. Unfortunately, in chronic infections such as leishmaniasis, maintaining functional CD4 cell counts becomes an important task as the immune system is continually activated to respond to the pathogen.

New immune defenders However, research conducted by Professor Steger in her laboratory at the INRS Armand-Frappier Research Centre for Biotechnology and Health suggests that these cells may have more than one way of maintaining their viability.

"We have discovered a new population of CD4 cells in mice infected with the parasite responsible for visceral leishmaniasis. These T cells have interesting properties," said Professor Steger.

By monitoring these new cells, the scientists noticed that their numbers increased during the chronic phase of the disease and that, like progenitor cells, they were capable of self-renewal or differentiation into other effector cells responsible for eliminating the parasite or into regulatory cells that suppress the host response.

Professor Steger notes that CD4 T cells normally differentiate into effector cells from "naive" CD4 T cells. But during chronic infections, due to the constant need to generate effector cells, naive CD4 T cells become overloaded and can become depleted.

"We believe that in the chronic phase of visceral leishmaniasis, the new population we identified is responsible for generating effector and regulatory cells. This will allow the host to prevent the depletion of the existing pool of naive CD4 T cells for a particular antigen," explains PhD student and first author of the study, Sharada Swaminiathan.

The new lymphocyte population discovered by the INRS team could become a crucial immune booster, replacing overloaded naive CD4 T cells.

"If we can figure out how to direct this new lymphocyte population to differentiate into defensive effector cells, it may help the host to get rid of the Leishmania parasite," said Professor Steger.

A cure for other infections? The study also mentions that similar cells have been found in mice infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and in mice carrying the intestinal worm H. polygyrus. So it is possible that this population is present in other chronic infections or other chronic inflammatory environments.

This fact opens up even broader prospects for the discovery made by Professor Steger's team. "If our hypothesis is correct, these cells could be used for therapeutic purposes not only for visceral leishmaniasis, but also for other chronic infections," the researcher concludes.