New publications

Gene editing to cure herpes shows success in lab tests

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

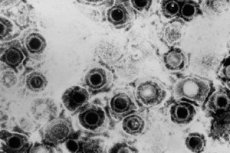

Researchers at Fred Hutch Cancer Center have found in preclinical studies that an experimental gene therapy for genital and oral herpes eliminates 90% or more of the infection and suppresses the amount of virus an infected person can shed. This suggests that the therapy may also reduce the spread of the virus.

“Herpes is very sneaky. It hides among nerve cells and then reactivates and causes painful skin blisters,” said Keith Jerome, MD, professor of vaccines and infectious diseases at Fred Hutch. “Our goal is to cure people of this infection so they don’t live in constant fear of outbreaks or transmitting the virus to someone else.”

Published May 13 in the journal Nature Communications, the study by Jerome and his team at the Fred Hutch Center represents an encouraging step toward gene therapy for herpes.

The experimental gene therapy involves injecting a mixture of gene-editing molecules into the bloodstream that seek out where the herpes virus is located in the body. The mixture includes laboratory-modified viruses called vectors, which are commonly used in gene therapy, and enzymes that act as molecular scissors. Once the vector reaches the clusters of nerves where the herpes virus is hiding, the molecular scissors snip the herpes virus genes, damaging them or removing the virus entirely.

“We use a meganuclease enzyme that cuts the herpes virus DNA in two different places,” said lead author Martine Ober, PhD, chief scientific officer at the Fred Hutch Center. “These cuts damage the virus so badly that it can’t repair itself. The body’s own repair systems then recognize the damaged DNA as foreign and get rid of it.”

Using mouse models of infection, the experimental therapy eliminated 90% of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) after a facial infection, also known as oral herpes, and 97% of HSV-1 after a genital infection. It took about a month for the treated mice to show these reductions, and the virus reduction seemed to become more complete over time.

Additionally, the researchers found that HSV-1 gene therapy significantly reduced both the frequency and amount of viral shedding.

Fred Hutch virologists Martin Ober, PhD, and Keith Jerome, MD, are conducting laboratory experiments to develop a gene therapy aimed at curing herpes. “If you talk to people living with herpes, many of them worry about whether their infection will spread to others,” Jerome said. “Our new study shows that we can reduce both the amount of virus in the body and the amount of virus shed.”

The Fred Hutch team also simplified the gene-editing treatment, making it safer and easier to produce. In a 2020 study, they used three vectors and two different meganucleases. The latest study uses just one vector and one meganuclease, which can cut the virus’s DNA in two places.

"Our simplified gene editing approach is effective in eliminating the herpes virus and has fewer side effects on the liver and nerves," Jerome said. "This suggests the therapy will be safer for people and easier to manufacture because it contains fewer components."

While Fred Hutch scientists are encouraged by how well the gene therapy works in animal models and are eager to apply their findings to human treatments, they are also cautious about the steps needed to prepare for clinical trials. They also noted that while the current study looked at HSV-1 infections, they are working to adapt the gene-editing technology to target HSV-2 infections.

“We are collaborating with many partners as we move toward clinical trials to meet federal regulatory requirements to ensure the safety and efficacy of gene therapy,” Jerome said. “We deeply appreciate the support of herpes cure advocates who share our vision of curing this infection.”

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a common infection that persists for life once infected. Current treatments can only suppress symptoms, but not completely eliminate them, which include painful blisters. According to the World Health Organization, about 3.7 billion people under 50 (67%) have HSV-1, which causes oral herpes. About 491 million people aged 15-49 (13%) worldwide have HSV-2, which causes genital herpes.

Herpes can cause other health problems in humans. HSV-2 increases the risk of HIV infection. Other studies have linked dementia to HSV-1.