New publications

Cardiomyocyte research reveals a new way to regenerate damaged heart cells

Last reviewed: 30.06.2025

All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Scientists at Northwestern Medicine have discovered a way to regenerate damaged heart muscle cells in mice, which could open a new avenue for treating congenital heart defects in children and heart damage after a heart attack in adults, according to a study published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) is a rare congenital heart defect that occurs when the left side of a baby’s heart does not develop properly during pregnancy, according to the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. The condition affects one in 5,000 newborns and is responsible for 23% of heart disease deaths in the first week of life.

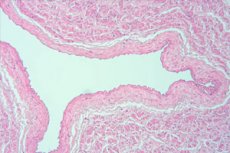

Cardiomyocytes, the cells responsible for contracting the heart muscle, can regenerate in newborn mammals but lose this ability with age, said Paul Shumaker, PhD, professor of pediatrics in the division of neonatology and senior author of the study.

"At the time of birth, heart muscle cells can still undergo mitotic division," Shumaker said. "For example, if a newborn mouse's heart is injured at one or two days of age, and then you wait until the mouse is an adult, when you look at the injured area of the heart, you'd never know there was an injury there."

In the current study, Shumaker and colleagues sought to understand whether adult mammalian cardiomyocytes could revert to the regenerative state of the fetus.

Because fetal cardiomyocytes survive on glucose instead of generating cellular energy through their mitochondria, Shumaker and colleagues deleted a mitochondria-related gene, UQCRFS1, in the hearts of adult mice, causing them to revert to a fetal-like state.

In adult mice with damaged heart tissue, the researchers observed that heart cells began to regenerate after UQCRFS1 was inhibited. The cells also began to consume more glucose, similar to how fetal heart cells function, according to the study.

The study's findings suggest that increasing glucose use can also restore cell division and growth in adult heart cells and may provide a new avenue for treating damaged heart cells, Shumaker said.

"This is the first step toward solving one of the most important questions in cardiology: How do we get heart cells to divide again so we can repair hearts?" said Shumaker, who is also a professor of cell and developmental biology and of medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care.

Based on this discovery, Shumaker and his colleagues will focus on identifying drugs that can trigger this response in heart cells without genetic modification.

"If we can find a drug that turns on this response in the same way as genetic modification, we can then stop the drug once the heart cells have grown," Shumaker said. "In the case of children with HLHS, this may allow us to restore normal left ventricular wall thickness. That would be lifesaving."

The approach could also be used for adults who have had a heart attack, Shumaker said.

"This was a big project, and I'm grateful to everyone involved," Shumaker said. "The paper lists 15 Northwestern faculty members as co-authors, so it was truly a team effort."